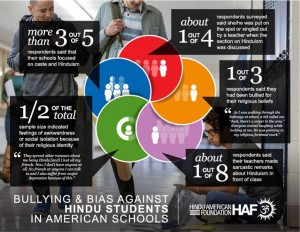

As a mother, I’ve drawn on my experiences growing up between cultures as an immigrant child to help my children live harmoniously between Indian and American culture—and rely on our faith foundation of Hinduism to help them find that balance. One can imagine my dismay on seeing the results of the Hindu American Foundation’s recently released report, Classroom Subjected: Bullying and Bias against Hindu Students in American Schools. It highlights the results and conclusions from survey responses collected from 335 middle and high school students during a six-week period in late 2015. The respondents were 6th to 12th graders; their answers help to show the different ways in which Hindu students can be singled out, bullied, and ostracized by their peers. It shows that we must find ways to help Hindu children have pride in their religious practices, particularly the pluralistic foundations of Hinduism, which can help them understand who they are, and how they see themselves. Hinduism’s inherently inclusive approach, where multiple perspectives can be respected, engaged and embraced, has helped me – and it is essential to me to provide my children the same spiritual foundation to help them navigate their place in the world.

As a mother, I’ve drawn on my experiences growing up between cultures as an immigrant child to help my children live harmoniously between Indian and American culture—and rely on our faith foundation of Hinduism to help them find that balance. One can imagine my dismay on seeing the results of the Hindu American Foundation’s recently released report, Classroom Subjected: Bullying and Bias against Hindu Students in American Schools. It highlights the results and conclusions from survey responses collected from 335 middle and high school students during a six-week period in late 2015. The respondents were 6th to 12th graders; their answers help to show the different ways in which Hindu students can be singled out, bullied, and ostracized by their peers. It shows that we must find ways to help Hindu children have pride in their religious practices, particularly the pluralistic foundations of Hinduism, which can help them understand who they are, and how they see themselves. Hinduism’s inherently inclusive approach, where multiple perspectives can be respected, engaged and embraced, has helped me – and it is essential to me to provide my children the same spiritual foundation to help them navigate their place in the world.

Years ago, I read and wrote about The Inner World of the Immigrant Child by Christina Igoa, which tells the story of one teacher’s journey to understand the inner workings of immigrant children, and to create an educational environment which is responsive to these students’ needs. The book’s findings resonated with my experiences as an immigrant child: I was happy to see that the author, a second language/bilingual educator, understood that academic achievement can not be divorced from the child’s context, and portrayed the immigrant experience of uprooting, culture shock, and adjustment to a new world. She said “Every culture has subtle signs by which people evaluate what they say and do. Losing these cues produces strain, uneasiness, and even emotional maladjustment if the person is received badly, because there is no longer a familiar foundation on which to stand.” Her advice that “one should stay connected to one’s own culture and also learn the cues of the new culture—a ‘both/and’ experience, not ‘either-or’” informed my parenting—and I knew that helping my children involved raising them to be proud and practicing Hindus.

However, key findings of the HAF report conclude that most Hindu children “highlighted a sense of alienation for being a different religion, particularly one not understood well in most U.S. classrooms or textbooks” and that “as a result, some respondents said they hid their religious identity in order to prevent or stop bullying.” One respondent even said, “After being made fun of by people I thought were friends, I didn’t tell anybody else I was Hindu so I don’t experience problems so much as I feel awkward sometimes.” This took me back to fourth grade, when my first crush made fun of me, calling me “dothead” for the bindi I wore on my forehead—a sacred, outward symbol of the inner practices of Hinduism. I was torn between my mother’s insistence on wearing it, and not wanting to be ridiculed. How disappointing to know that the current context for Hindu children has not moved beyond what I experienced in my childhood – and perhaps has even gotten worse!

Yet there is hope, ranging from poetry to public awareness campaigns, that can help enable Hindus—children and adults alike—to be free from alienation. We can define what Hinduism is and even “take back” the terms within it. Ohio Poet Laureate, Amit Majmudar, recently was interviewed on NPR, and spoke of his new book, Dothead, and on the way the history of India was taught in his mostly white school:

Naturally they’re going to teach the most interesting things. And “interesting” meaning the most barbaric customs of the past. And when a bunch of high school aged kids are taught about widow burning and the caste system and all those things, it’s hard to make them realize that it doesn’t mean anything to me, and it’s not what makes me Indian, and it doesn’t have anything to do with my Indianness or my Hinduism. And I think that was part of the problem, for me. The sense that I was being associated with things that didn’t really matter to my experience of my religion and my experience of my parents’ culture.

Many public figures such as Dr. Majmudar have endorsed the Foundation’s report, aware that our faith has helped us answer those essential questions of who we are, and that it is important to move beyond the burden and shame of being isolated and alienated.

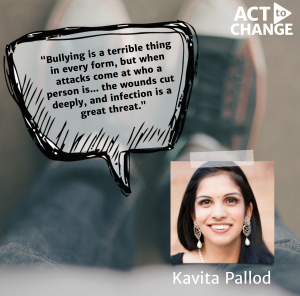

And fortunately, the Act to Change campaign helps move us from awareness of bullying and bias, to action: “Learn about it. Talk about it. Stop it.” The campaign, likes its title, seeks to enable people to do something, including in the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. As the website says, “Kids and teens are bullied in schools all across the country. Unfortunately, many AAPI youth who are bullied face unique cultural, religious, and language barriers that can keep them from getting help. This campaign aims to empower students, families, educators with the knowledge and tools you need to help stop and prevent bullying in your communities. Bullying is a problem that affects us all and we must act together to put an end to it.” The campaign is a call to action for all—take the pledge to protect all students—and the HAF report is a clarion call for Hindu parents and adults to strengthen our advocacy and education efforts. Kavita Pallod, my colleague at the Foundation, co-author of the report and a former elementary educator, says “As an adult, the only balm I’ve found is in remembering that a textbook, a teacher, or a confused friend can’t define who I am, or what my faith is. I define my narrative. The prouder I am of that, the easier it is for my siblings, for my nephews and nieces, for the kids I’ve mentored, to own who they are as well.”