I just read an article in First Things, called “First Church of Intersectionality,” by Elizabeth Corey. Her article was timely, in that I’ve been, over the last several months, reflecting more and more on what it means to have a body. To be a body. To move through life in a female body. In a body with fair skin. In a body that’s both given life and been the scene of a crime.

In delving into the riches of Catholic teachings on justice and social issues, I come back again and again to solidarity. As far as I can tell, intersectionality is what solidarity looks like with skin on, and rather than waging war on intersectionality, we as the church need to be engaging with intersectionality in a genuine way, for there are many points of contact along the way. Let’s unpack this a little further.

Corey says in the first paragraph that “many of the participants smelled of curry and incense.” I can’t help but believe, since Corey is an expert in social justice, that she would have realized the casual racism (or just making fun of liberals – who can tell the difference these days?) of her opening paragraph. Women with shaved heads, Birkenstocks, and baggy black clothes? Can someone fetch my smelling salts please?

The focus of her article is to critique the movement of intersectionality in academia–based largely, it seems, on her attendance at one particular academic conference. I can only speak to that so much, since it’s been years since I completed my work in social justice at a Catholic university. Yet in the intervening years I have moved in circles with people working towards intersectionality and justice, and can offer reflection from that perspective.

In critiquing the lecture she attended, Corey says,

“she charged the audience to form nonhierarchical networks of flexible solidarity, coalitions of conscience, made up of people who would devote themselves to upending the status quo…Nobody seemed to notice (or mind) that this was precisely the same language that radicals of all stripes have employed for at least the last fifty years”.

Perhaps I’m not a sharp as I once was, but I have to ask: what’s wrong with creating networks of solidarity where everyone is equal, and people come together around issues of conscience to devote themselves to making meaningful social change? Is it ok if people come together to do those things to try and outlaw abortion? Is that the only time we’re allowed to talk about social change?

She then states, somewhat aghast, that this is the kind of dangerous talk that “radicals” embrace.

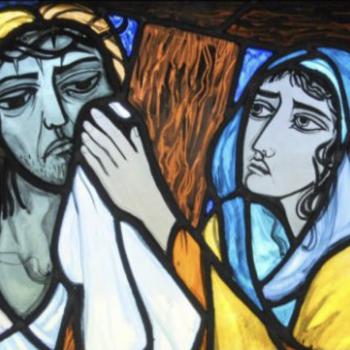

Radicals like … Christ? Jesus, who ministered to the least, the last, and the lost every day of his life and who was, the least and the last? God with skin on who inhabited the body of a man born into poverty and who inherited exile and government occupation due to being a religious minority?

Radicals like Jesus of Nazareth, who toiled for his bread and gave without asking the cost, and saw the sacred core of dignity and goodness at the heart of each member of his creation unreservedly? And who exhorted his followers to literally eat his flesh and drink his blood so we may be strengthened to use our human hands to bring his kingdom of justice and flourishing – thy kingdom come, thy will be done?

Like my Savior, whose radical love was so dangerous to those in power that the religious minority colluded with their oppressors to have him murdered? Like that kind of radical?

As though any part of Christianity isn’t the most radical thing the world has ever seen.

Radical means “root” or going back to the roots of something. So, what’s at the root of intersectionality? Justice — and love for human bodies. What’s at the root of solidarity? Justice and love for human bodies with immortal precious souls.

What’s at the root of injustice, of the unequal distributions of power, possibility, and liberty in our world? Evil. I’ll say it again for the folk in the back. Evil stands squarely at the root of injustice, and it is not only radical to root it out, it’s part of our call as baptized Christians. Really what we need is more, not fewer, radicals.

Corey then makes a somewhat bold claim that intersectionality stands as kind of modern Gnosticism. Yet Gnosticism seeks a shrugging off of the body, of one’s particular embodied reality, to live solely from the brain. The severing of body and soul, and the secret knowledge that only a select group can attain, couldn’t be more distant from the intersectional justice I know. The people devoting themselves to lasting social change that I have known are very much living an embodied reality and the reality of violence, aggression and discrimination against human bodies – black, brown, female, disabled, LGBTQ+, poor – is at the forefront of their minds.

Secondly, while intersectionality may seem inaccessible to some people, the concept is straightforward. That many folks struggle to see or accept the reality of intersecting layers of oppression may have more to do with willful ignorance than an overly complicated principle.

Corey then detailed the stories shared by women of color in the audience, of the ways that they have experienced alienation and discrimination both personally and professionally. The stories hang there in the ether with no comment on the injustice she just recounted – the suffering of sisters in Christ. Instead she says,

“Expressions of hurt and exclusion were inevitably followed by anger at the system – at the patriarchy, racism, unjust institutions, and structural prejudices – and then by exhortations to do something about it.”

Once more I have to wonder, what’s wrong with that response? If someone repeatedly suffers injustice at the hands of a broken system, who could dare be shocked when those people become angry at that system? Should the families of Trayvon Martin and Rakia Boyd and Sandra Bland and Jordan Edwards and Tamir Rice and Emmit Till and all the unnamed men and women violated and murdered for inhabiting the wrong color body just smile and nod? What is an appropriate response to the evil of injustice but anger — which inspires us to work to change and dismantle broken systems?

Corey describes their righteous anger and action as “rebelling against the poor organization of the world, and maintained the hope of salvation through human effort.”

Oh man. Another word for “poor organization of the world” would be evil and sin. Another word for “salvation through human effort” is working for justice – that is being in right relationship with God and others – because God told us with his very own human mouth to build his kingdom and to hunger and thirst for justice.

Corey ends her article by comparing intersectional justice to a form of religion, and citing that this will necessarily end with “a long and bitter fight.” But what I see is a tremendous opportunity to engage with wounded human beings, whose very bodies have been used against them, to create a culture of encounter where we meet people as they are sharing the good news of God’s kingdom – the circle of kinship drawn so wide that no one is outside of it. When we can start to see intersectionality as a particular expression of solidarity, then we can continue building the kingdom.

Sarah Margaret Babbs is a regular contributor to Sick Pilgrim. She blogs at Fumbling Towards Grace.