J.M. Coetzee has been awarded the Nobel prize for literature.

I'm afraid I've only ever read one book by Coetzee, and it was a short one — the novella Waiting for the Barbarians. My one encounter with Coetzee, however, was a case of the right book at the right time. If his other works have had a similar impact on his other readers, then Coetzee's Nobel honors are well deserved.

Barbarians is an extended parable about guilt and responsibility, knowledge and innocence. It describes — in the word's of President Bush's favorite devotional writer, Oswald Chambers — how we are responsible "for what we refuse to look at."

Coetzee's protagonist is a middle class magistrate in a frontier town of an unnamed Empire. He is not particularly wealthy or powerful, and he has had little reason or inclination to wonder about the source of the Empire's wealth and power. "I have not asked for more than a quiet life in quiet times," he says.

Then one night, "I took a lantern and went to see for myself." He sees a man — an old man, a foreigner, a "barbarian" and an innocent — who has been killed by an interrogator representing the power of the Empire. Until that night, the magistrate had been half ignorant, half in denial. But now he knows. And knowing, he must act.

I ought never to have taken my lantern to see what was going on in the hut by the granary. On the other hand, there is no way, once I had picked up the lantern, for me to put it down again.

Coetzee's story had obvious implications for the author's specific context — Coetzee is a white South African born in Cape Town. But it is also a universal story.

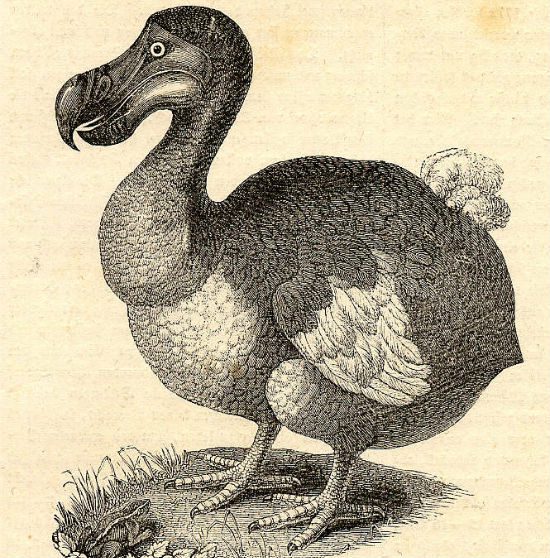

My favorite version of this universal story in recent years involves a guy named Xander Harris. Like Coetzee's magistrate, Xander is an unremarkable fellow — a schlemazel and a bit of a coward with no particular talents. He is an unlikely hero. But like the magistrate, Xander takes up a lantern one night (a flashlight, actually) and gained a knowledge that entailed a responsibility. He learns that there are powerful evils in the world, forces that prey on the weak and the vulnerable.

Once you learn this, what do you do about it?

"There are some [people] in the world who were born to do our unpleasant jobs for us," Miss Maudie Atkinson says in To Kill a Mockingbird. But most of us aren't born heroes, like Atticus Finch, or like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, "born with the strength and skill to fight the vampires, to stop the spread of evil."

We're more like Coetzee's magistrate, or poor, overwhelmed Xander, with no special powers, no superhuman "strength and skill."

Yet here we are, lantern in hand. And the monsters and the Empire are real. "A quiet life in quiet times" is no longer an option.

So what do we do?