If you want an acerbic taste of what might be called Niebuhrian irony, see the gallows humor of American soldiers in Chris Collins’ front-line* McClatchy report from Iraq, “South of Baghdad, U.S. troops find fatigue, frustration“:

Standing in a small room in the Iraqi home they’d raided an hour earlier, a dozen soldiers from the 3rd Heavy Brigade Combat Team of the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division were trading jokes when 1st Sgt. Troy Moore, Company A’s senior enlisted man, shouted out.

“We’re bringing democracy to Iraq,” he called, with obvious sarcasm, as a reporter entered the room. Then Moore began loudly humming the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Within seconds the rest of the troops had joined in, filling the small, barren home in the middle of Iraq with the patriotic chorus of a Civil War-era ballad.

The “Battle Hymn of the Republic” embodies exactly the kind of naively revolutionary, millennial optimism that Reinhold Niebuhr made a career out of shouting down. Due to my preoccupation with the scatological eschatology of our friends LaHaye and Jenkins, I’ve tended to spend a lot of time here with the errors and oddities of premillennial dispensationalism. But that is only one form, and not even the dominant one, of the millennial fervor that has, periodically, played such a large role in American Christianity and American history. The “Battle Hymn” is the almost-official theme song of that millennial fervor.

When performed well, the song can give you a sense of the attractiveness of that millennial spirit. That allure, and its influence in our culture and history, is reflected in the many echoes of Julia Ward Howe’s lyrics in our literature and political rhetoric. It is a beautiful song,** but it is also, explicitly, a crusader’s hymn. It is a distillation of the Civil War minus all of Lincoln’s doubt, sorrow and humility. (Look again at his Second Inaugural, which serves almost as a rebuttal of this song.)

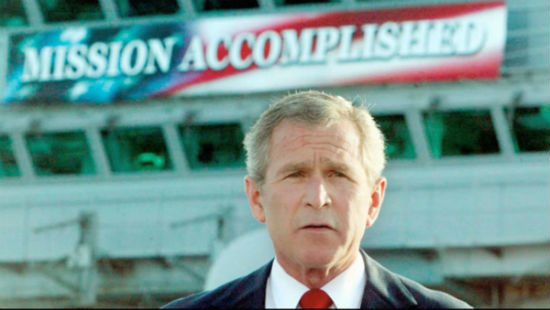

The arrogant, vainglorious dreaming of the Project for a New American Century — the people who pitched and promoted, but never planned for, this war — is the latest expression of this millennial optimism. That implicit millennial vision has at times been stated explicitly, as when Condoleezza Rice spoke of the recent fighting in Lebanon as the “birth pangs” of democracy in the Middle East (an allusion to the mini-apocalypse of Matthew 24). The dreamers of PNAC preached a “fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel,” but the soldiers of Company A know better. The Lord hasn’t been seen in their hundred circling camps.

American millennialism needn’t be as explicitly religious as the “Battle Hymn,” although even in its most secular forms it remains a kind of religious faith. One of the most memorable portrayals of this secular millennialism is that of Alden Pyle, the title character in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, of whom Greene’s narrator, Fowler, says, “I never knew a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.”

In an astonishing speech last month*** President Bush attempted to cite The Quiet American — including that very description of Pyle — as part of some sort of argument for why the American occupation of Iraq must never end. I’ve been too flabbergasted by the perverse audacity of that to comment on it (Greg Mitchell does a good job of responding), but here’s a bit of a post I wrote on all of that back in mid-December, 2003:

Greene’s most important novel today has to be The Quiet American, in which he tells the tragic story of two unlikely friends: Thomas Fowler and Alden Pyle.

Fowler is world-weary, disillusioned and, if not exactly corrupt, thoroughly compromised. Pyle is in many ways his opposite — young, naive, idealistic. Pyle, Fowler tells us, semi-reliably, was “determined … to do good, not to any individual person, but to a country, a continent, a world.” He was innocent, and therefore dangerous: “Innocence always calls mutely for protection, when we would be so much wiser to guard ourselves against it; innocence is like a dumb leper who has lost his bell, wandering the world, meaning no harm.”

The two men are presented as opposites — one disillusioned, the other illusioned. If you read the novel — and the world — convinced that Pyle and Fowler represent the only available options, then you are left with despair. Surely there is some option available to us other than inhuman detachment and the violent idealism of plastic explosives.

When one reads the audacious plans of the PNAC … in the light of Greene’s novel, what’s striking is the way its authors seem to combine the worst elements of both Fowler and Pyle. It exhibits both Pyle’s unbridled, hubristic idealism and Fowler’s cynical regard for the naked power of imperial hegemony. …

What’s particularly annoying — and offensive — is the habit that the PNACes have of treating all of us who disagree with their destructive Pylesque idealism as though we are defenders of Fowler’s cynical views (the old “you’re objectively pro-Saddam” sophistry). This accusation reveals a despairing failure of imagination, as well as a refusal to listen to what is actually being said. …

That failure of imagination and refusal to listen — to critics, to reality — were on full display in Bush’s speech, which concluded with this starkly millennial assertion:

So long as we remain true to our ideals, we will defeat the extremists in Iraq and Afghanistan. We will help those countries’ peoples stand up functioning democracies in the heart of the broader Middle East.

Glory, glory hallelujah. Let’s loose the fateful lighting of “our ideals.” But yet, as tends to happen, the terrible, swift sword has come to supplant the ideals we claimed it served. The soldiers of Company A appreciate that, even if Bush doesn’t.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* The front-lines, in this case, being the living room of a private home. The purveyors of the stabbed-in-the-back myth of Vietnam like to say that war was really fought in the living rooms of America, as the public watched it unfold on their televisions. These same revisionists, hoping to escape accountability for the current unwinnable war, are pitching the same lie about the conflict in Iraq. It turns out the lie is partly true, though, since this war is literally being waged in living rooms, just not in American ones.

** The “Battle Hymn of the Republic” was quite probably the first music I ever heard. It was playing on every radio and television in the hospital the night I was born. I don’t remember this, of course, but I have since seen footage of that rendition. The song was sung by two choirs at the Lincoln Memorial, accompanied by the brass section of the U.S. Marine Band and all the residents of Resurrection City. It was the end of a long day, a day that began with a funeral in New York and ended with the only night-time burial in the history of Arlington National Cemetery. That grave context made the song something other than a shallow expression of millennial optimism. It became instead, as it was in the speeches of the man buried two months earlier, an expression of millennial hope. And hope and optimism are not the same thing. I sometimes even think they may be mutually exclusive.

*** Read that speech and you’ll see what I mean about the dolchstosslegende.