I want to turn here away from the doctrine of Hell in itself to explore briefly a bit of the folklore that has attached itself to it. Specifically I want to look at the odd notion that Hell exists as a physical location that is also the workplace of hordes of devils and demons. That is, the idea that Hell is a place where such creatures are employed rather than a place where they are punished.

I refer to this as folklore because it isn’t actually part of any official dogma or doctrine. It is not, to be clear, something that those I’ve been calling Team Hell believe to be true. Their selectively literalist reading of Matthew 25 differs greatly from my own understanding of what that passage is saying, emphasizing Jesus’ reference there to “the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” and interpreting that as a didactic teaching about the specific reality of such a place, rather than an emphatic allusion intended to stress the main point of the story (feed the hungry, clothe the needy, comfort the sick). But they do not believe any more than I do that it refers to Hell as a place “prepared for the devil and his angels” to help them find gainful employment.

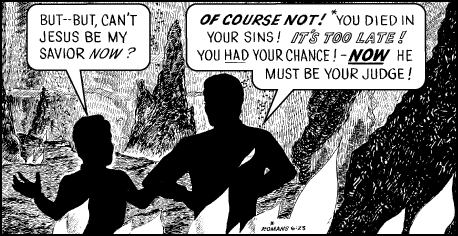

Yet this idea persists, dogging the contentious doctrine of Hell throughout the centuries and inextricably binding itself to it. This is an unavoidably common image conjured up by the word “Hell” — this unshakable idea of a fiery landscape dotted with horned, goat-footed creatures tormenting the damned with pitchforks. No matter how cautious and studiously precise the theologians of Hell try to be in defining that place or state, this idea always lingers close at hand — the connotation to their every denotation.

On the one hand, this is a very strange bit of folklore. Why should these devils and demons escape the punishments being meted out to mortal sinners? “Better to reign in Hell than to serve in Heaven,” Milton’s Satan said, but where did either Milton or his Satan get the idea that he would “reign” there? Why has it become common to think of Satan as something like the CEO of Hell, rather than one of its prisoners? Why have so many preachers and artists — dating back many centuries before Milton — seemed so convinced that Satan would be a torment-or in Hell, rather than a torment-ee?

From that angle it doesn’t make much sense. But viewed another way, the idea has a compelling logic to it.

Let’s stipulate that the damned are to be tortured for eternity. OK, then, who exactly will be doing the torturing? It seems unseemly to imagine God directly involved, personally poking the gangrenous flesh of sinners with a heavenly pitchfork. And it’s unimaginable that this eternal duty could be delegated to the angels, who desire nothing more than to spend eternity in the presence of God, singing praises. Nor could this task be delegated to the saints. They’re saints, after all, and thus such an assignment would be for them an eternal punishment nearly rivaling that of the souls they would be assigned to torment.

This job, if it must be done, is clearly devils’ work. Only a fiend could carry out such an assignment. Only a demon — a monstrous, soulless, malevolent and wholly unholy creature — could devote itself to eternal torture, unrestrained by mercy, unhampered by revulsion or repugnance.

And thus we come to the paradox of pitchforks. Any creature capable of eternally wounding another creature with a pitchfork lacks the authority to wield that pitchfork, rightfully belonging at the other end of it. The pointy, business end of it.

What the paradox of pitchforks means, of course, is that this enduring bit of folklore doesn’t really work. It doesn’t solve the problem it sets out to solve. It kicks the can a bit down the road, but doesn’t ultimately address the uncomfortable question it arises to deal with, namely the disturbing thought of God’s culpability in this unholy devils’ work. Here the idea of devilish sub-contractors working on God’s behalf does no more to protect God from complicity than the charade of “extraordinary rendition” does to protect the United States from complicity in the abuse of those we allegedly handed over to be tortured. All those goat-footed devils in the medieval frescoes and illuminated manuscripts, this idea says, are God’s proxies — God’s servants, God’s employees.

And so we’re back at the original problem, putting the pitchfork back into the hand of a fiendish God. That was the very disturbing notion that I believe prompted us to concoct this whole devils-and-pitchforks business to begin with.

Not everyone finds this notion disturbing, however. Some argue that God is not subject to the paradox of pitchforks because God is perfectly holy and perfectly righteous and therefore perfectly capable of tormenting a suffering creature with a pitchfork, eagerly, forever, without any loss of moral authority. I understand the form of this argument, but it seems to be based on several words not meaning what I think they usually mean.