Change can be unpleasant.

Unless you’re down and out. If you’re down and out, then change is probably good news. When you’re down and out, then any change is likely to be progress.

But if you’re neither down nor out, then progress may be unwelcome. You’re on top. You’re in. Why mess with that?

The last 60 years has seen a lot of change. The trajectory of that change has been good news for many people who used to be intractably down and out. For them, the trajectory of this change is clearly progress. But such progress has been unsettling for many people who used to enjoy an exclusive birthright to being up and in.

What I’m trying to talk about here is privilege, hegemony, implicit hierarchy. And about the lingering resentment and anxiety over every slight erosion of them.

What I’m trying to talk about here is privilege, hegemony, implicit hierarchy. And about the lingering resentment and anxiety over every slight erosion of them.

This shows up a lot in pronouns — particularly in the ambiguous use of undifferentiated first-person plural pronouns. “We need to take our country back.” But what do you mean “We,” kemosabe?

Those pronouns are funny things. They seem to be inclusive and comprehensive. On its face, “we” means us — all of us. But we don’t always use “we” in that way. Who is the “we” in “we need to take our country back”? Who is the “our”?

It’s inclusive, but not comprehensive. Or, in other words, it’s tribal — inclusive of those within the tribe, but exclusive of those without it.

The tribal boundaries are implicit and unstated, but they are known. These boundaries are ethnic and religious and sexual, yet they do not necessarily entail any ethnic or religious or sexual animus.

There may be such animus, but it’s not necessary. No actual dislike or contempt needs to be felt. Personal sentiment and emotional antipathy are wholly optional when it comes to defending the interests of the tribe.

This can lead to some confusion and muddy things up. We can end up arguing about racism, misogyny, homophobia or religious hatred with folks who insist, sincerely, that they do not have any such feelings.

And for many people, that’s largely true. They don’t feel such dislike, and some of their best friends are, etc. Because this isn’t about feelings, it’s about tribes. Plenty of people who are driven by the desire to defend the interests of their tribe don’t feel any visceral dislike for those they regard as outsiders — as not “we,” not “us,” not “ours.” Those folks just happen to be on the other team.

And if our team is going to win, they imagine, then their team can’t.

I think that’s the key. That, right there, is the idea that makes personal feelings of dislike or hatred superfluous. Once you accept the framework of a zero-sum struggle between competing tribes then it no longer matters whether or not you feel any such feelings — you’re still bound to regard any advance for them as a loss for us. You’ll still imagine that “we” cannot be up and in unless “they” are kept down and out.

In that zero-sum tribal framework, it doesn’t matter whether or not you dislike the other tribe or view them an inferior. If you think of yourself as part of the straight, white, male, Christian tribe, then you’ll defend the interests of that tribe against anyone who is not straight, white, male and Christian. Whether or not personal sentiments of antipathy are involved, the effect is the same.

It’s very difficult, if not altogether impossible, to separate out the various threads of tribal identity as distinct factors. The tribal anxiety that comes from the idea of a zero-sum world is all of a piece. Antitribalism struggles to be “intersectional,” but tribalism has always been intersectional. Tribalism was intersectional before intersectionality was cool.

Look again at that amorphous and undifferentiated use of the tribal “we.” We need to take back our country. The anxiety there — the sense that we are losing, somehow, due to the advances made by others — cannot easily be separated into discrete elements of ethnicity, gender, religion or sexuality. The loss that “we” feel for “our” tribe arises from a host of changes that combine to form a single anxiety. The anxiety that perceives the repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell as a tribal defeat is bound up with the anxiety that festers behind fear of the so-called “War on Christmas.” The tribal anxiety felt over every advance of feminism is intermixed with the anxiety felt over every advance in civil rights for ethnic minorities. The sense of tribal besiegement that perceives a same-sex wedding as some kind of setback is intermingled with the anxiety over the new neighborhood mosque, the ending of prayers at high school football games and “Press 2 para Español.”

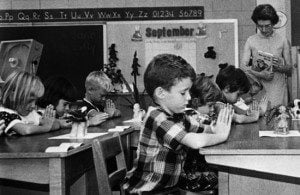

This is part of what I was trying to convey with the Venn diagram I posted last night. State-mandated sectarian prayer in public schools is a theocratic idea, yet “school prayer” isn’t primarily a rallying cry for theocrats, but for tribalists. The 1962 decision forbidding mandatory sectarian prayers was perceived as a loss for the tribe, just as the desegregation decisions of the previous decade were. “We” were losing control of “our” schools.

Racial animus may play a role in that tribal anxiety, for some. And I suspect that for many who harbor such feelings of racial animus, “school prayer” is considered a safer, more acceptable-seeming way of expressing their objection to desegregation. But explicit, visceral racial animus is not necessary for such an objection any more than state Sen. Dennis Kruse needed to be a raging anti-Semite to introduce legislation allowing Indiana schools to mandate the recitation of the Christian Lord’s prayer. It doesn’t really matter whether or not Kruse feels any such feelings of bigotry — the effect is the same either way.