The Bible is a library disguised as a book. The two testaments of the Protestant Bible include 66 different books, many of which are themselves anthologies. And everything, in all of them, is canonical.

That gets a bit messy sometimes. Consider, for example, the book of Jonah — a vicious, devastating polemic against a particular strain of religious exclusivism. Jonah is canon. But so are books like Ezra and Nehemiah, which take the opposite side of this argument. In one sense, that’s perfectly logical and necessary. We can’t understand such an argument unless we’re given both sides of it. But in another sense, this is frustrating, because in making both sides of the argument canon, neither side is granted the definitive final word. That leaves the argument unsettled — something many readers find unsettling.

This is an especially big problem if you think of the canon of scripture as something that’s supposed to be, above all, the final authority for definitively settling all disputes. If the canon itself is a library that includes diverse and competing views, then how can we rely on it to help us sort out the correct view from all the other possibilities? (Or, less charitably, how can we use it to prove that we are right and others are wrong?)

This is why the more authoritarian someone’s view of the Bible is, the less likely that person is to admit or acknowledge the enormous diversity that exists within the canon, within this library disguised as a single book. They tend to be rather hostile to the presence within the Bible of ongoing arguments, or different, incompatible versions of various stories.

That the Bible does, indeed, contain very different versions of various stories is fairly obvious if you pick it up and start reading at the beginning of either of the testaments. Matthew’s Gospel begins with a genealogy and a nativity story. So does Luke’s Gospel. But they are not the same genealogy and nativity story. Genesis starts with a creation story. And then it follows that with a different creation story.

Right off the bat, then, we have a choice to make. We can choose to accept that this apparent variation is a feature of the book(s) we are reading, and we can then go about trying to learn what such variation has to teach us. Or we can choose to say that this appearance of variation is a problem that must be solved, and we can then go about trying to explain away every such apparent instance of variety, dispute or diversity within the canon in order to buttress our notion that it serves as a clear, simple, unequivocal and univocal authority that can be cited chapter-and-verse to settle all disputes and answer all questions.

This second choice is quite popular. It’s so popular, in fact, that even those of us who choose the former approach still can’t help but absorb some of the imaginative solutions concocted in order to deny the diversity of the canon.

James McGrath wrestled with this in a post yesterday titled “How Many Adam?” He was surprised to realize one of the things he’d absorbed about the creation story in Genesis 1 even though it’s not in the Bible.

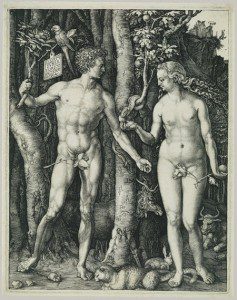

Yesterday in a Facebook group I participate in, it was pointed out that, unless one has the Genesis 2 creation account in mind, when one reads Genesis 1, one will not necessarily get the impression that God, creating Adam (which means humankind) male and female, made only one of each.

I’d put that in stronger terms than “one will not necessarily get the impression.” The story in Genesis 1 speaks of “multitudes.” Two people does not a multitude make.

This is important. Genesis 1 is not about Adam and Eve. They are not characters in that story. I’m emphatic on this point because the text is emphatic on this point. Let me quote from a post from last October (“Things that are not in the Bible: ‘In the creation account, God creates Adam and Eve, the world and everything in it in six days“):

In the first story and the first chapter in Genesis, God creates “humankind” on the sixth day of creation. Humankind was created “male and female” and is spoken of as plural throughout this story, but the story never says that only two humans were created on the sixth day. (Two doesn’t seem like much of a multitude.)

That same word for humankind — adam — reappears in the second story that begins in the second chapter, but there it appears as a proper noun, as the name of an individual character, Adam. In our English translations of Genesis, that Hebrew word adam is always translated into English in the first story — “humankind,” or “mankind,” or “man” — because there it is plural and clearly not an individual’s name or a proper noun. In the second story, however, the word is presented differently. It is capitalized and left untranslated to indicate that here — unlike in the first story — it is being used as the name of a single individual.

That post was in response to a CNN article garbling the difference between the different stories in Genesis 1 and Genesis 2. Maybe that’s to be expected from CNN, but earlier we discussed this same mistake when it was made by theologian and top-notch biblical scholar N.T. Wright. In discussing the notion of a historical Adam and Eve, Wright suggested the possibility of “God choosing Adam and Eve from others to be the ones with the image of God.”:

“God choosing Adam and Eve from others to be the ones with the image of God” is something that never happens in the Bible. That’s the opposite of what happens in the Bible. The first story says that all of humanity is made in the image of God, and we can apply that to the second story to infer that, because Adam and Eve are humans, that is also true of them. But these two stories cannot be made to say that Adam and Eve bear the image never attributed to them in their story while “others” do not bear the image attributed to them in theirs.

Any attempt to explain why “God [chose] Adam and Eve from others to be the ones with the image of God” is bound to be as helpful and insightful as trying to explain why God chose Adam and Eve to build an ark, or why God chose Adam and Eve to face Goliath armed only with a sling. Wrong story.

This matters. Smushing together the two separate stories in Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 together changes the text and leads us to conclusions not supported by the text itself. It can be particularly troublesome when we confuse the two stories in just the way Wright does above. Take the “image of God” bit from Story No. 1 and puree it together with the “Man’s First Disobedience, and the Fruit / Of that Forbidden Tree” stuff from Story No. 2 and you’ve got the makings of a theory of original sin that contradicts both stories — a theory based not on scripture, but on the scaffolding of “harmonizing” we’ve built around it.

This is the problem with so much of the creative solutions we’ve invented to “harmonize” away the diversity within the canon itself. The fanon winds up replacing the canon.

“Fanon” there is a term from the world of fan fiction. It combines the words “fan” and “canon” to refer to extra-canonical ideas that are so widely accepted in the fandom that they have acquired a kind of canonicity of their own.

I think this is a useful, clarifying concept in thinking about “canon” in its original, biblical sense. The distinction between canon and fanon may be helpful in sorting out the difference between the text itself and that whole scaffolding of attempts to “harmonize” away its diversity — all that stuff we’ve absorbed for so long that we’ve come to assume it’s there in the canon, even though it’s not.