“The Twelve Days of Christmas” is one of the stranger things about the 67 or so days of our holiday season. It’s a beloved Christmas carol, except for not really being a carol, or really being beloved, or having much of anything to do with Christmas.

And yet here it is, every year, an inescapable part of American Christmas and a tradition that gets dragged out year after year even though most of us can’t abide hearing it unless the performance involves Muppets or McKenzies, or having it dragged and deconstructed like in that Straight No Chaser arrangement. (If you somehow haven’t seen that yet, you should, even though you’re probably reluctant to click on the link because no one likes “The 12 Days of Christmas.” Their rendition quickly falls apart and ultimately devolves into Toto’s “Africa,” to the delight of the audience, because we all would much rather hear Toto’s “Africa” than yet another rehash of “The 12 Days of Christmas”).

The song starts — “On the first day of Christmas, my true love gave to me …” — and we feel trapped, as though we’ve volunteered to chaperone a middle-school class trip and, as the bus pulls out of the parking lot, the kids start singing, “99 bottles of beer on the wall, 99 bottles of beer …”

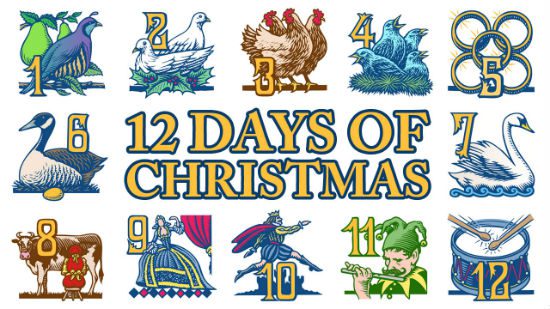

I’d say that’s what this song is — the “99 Bottles of Beer” of Christmas — except that’s not really fair to “99 Bottles of Beer,” because at least that song makes sense. I mean, I’m not really sure why we’re keeping our beer “on the wall,” instead of in the refrigerator (or probably in a bathtub full of ice, really, since that’s what most of us would end up doing if we had 4.125 cases and enough guests to drink all of it). But the basic notion of hanging out and sharing some beverages is certainly more familiar than the idea of demonstrating one’s true love by giving one’s beloved 42 swans, 36 turtledoves, and an assorted host of other birds.

Sure, it’s nice to imagine getting a load of presents every day from Christmas right on up through Epiphany. And five golden rings would seem like a very nice present — even after being repeated for over a week (you could hock 32 of them and still have one for every finger). But, geez, what’s with all the birds?

I like birds, I do. But I’ve never once asked for a swan for Christmas, let alone 42 of them. I don’t know anyone who has. “The good news is you’re getting something nice for Christmas. The bad news is you’re going to need to acquire a dozen ponds …”

Nobody knows what this song means. That’s true of several other Christmas carols of similar vintage (who the heck is King Wenceslas?), but most of us don’t learn all the words to those centuries-old songs the way we’ve all — voluntarily or involuntarily — learned the words to this one. The difference here, I think, is that its lyrics are understandable at face value, but wholly inscrutable at any other level.

“On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me / A partridge in a pear tree.” We understand that sentence. We understand the meaning of “Christmas” and of “partridge” and of “pear tree.” But we don’t understand why anyone would begift anyone else with this odd combination, of all things. And every additional “day” of gifts only compounds our bewilderment. More birds, more birds, more birds, some jewelry, more birds, and then suddenly a flood of practical and impractical laborers. I’d have to drink at least 99 bottles of beer before that started making any sense to me.

It’s likely that the reason these lyrics seem arbitrary and nonsensical is because they’re supposed to. “The 12 Days of Christmas” probably didn’t start out as a Christmas carol, but as a children’s memory game. Probably, actually, it started as a children’s memory game in French, the words of which got mangled and modified when it was partly translated, partly phonetically transferred into English.

The Wikipedia entry for the song provides a fascinating, passionately researched and judiciously inconclusive discussion of its long history and strange evolution. A written version of the song was first published in 1780, but unwritten variations are likely hundreds of years older than that. It is, the entry notes, a “cumulative” song, “meaning that each verse is built on top of the previous verses,” and while “The exact origins and the meaning of the song are unknown,” it tells us, “it is highly probable that it originated from a children’s memory and forfeit game.”

We still have games like that. Lap, clap, snap, snap. “Concentration, are you ready? Concentration, let’s go.” Or think of Simon, the early hand-held electronic game where we tried to imitate the patterns of flashing lights, beeps and boops. The Muppets and McKenzies and the singers in Straight No Chaser, then, are keeping true to the original spirit of the song when they start tripping over the order of days and scrambling the various gifts associated with each one. That’s what was supposed to happen. “Seven swans a swimming, six … um … six …” “Ha! You’re out!”

Yet this history of the song’s actual nature is largely unknown and obscured. We hear it today as a song — a “Christmas carol” — rather than as the game it was intended to be. And because we humans like to make sense of things — even of things that are, by design, nonsensical — we start to imagine or to ascribe meaning to this song’s litany of days and gifts and birds, birds, birds.

The best way to try to make sense of its nonsense is to ask the kinds of questions that good scholars tend to ask about any old text. Where did this come from? Who composed this? Who was it written for? And why? (The basic reporter’s craft of asking WWWWHW? always seems to be useful.) But that’s a lot of work.

It’s easier — and sometimes a lot more fun — just to guess. To speculate. To try to “decode” the song without any reference to its actual original composition and context. And so we concoct fanciful allegories that supposedly reveal the song’s “true” hidden meaning. It’s a Christmas song, after all, so it must mean something Christmas-y. The partridge is Christ and the pear-tree is the manger in Bethlehem. Or maybe the pear tree is Christ and the partridge is the church. And the 12 lords a leaping are the 12 apostles. Or, wait, the 12 apostles are the 12 drummers drumming … (Ha! You’re out!)

This happens a lot with this song. Search for the “true meaning” or the “hidden meaning” or the “secret meaning” of “The 12 Days of Christmas” and you’ll find dozens of responses besides that Snopes link at the start of this paragraph. We like the idea of knowing the true, secret, hidden meaning of things. Gnoing the gnosis makes us feel special — far more special than we could ever feel just from studying the actual history and context and intent of this initially bewildering old text.

Or, of course, of any other initially confusing old text.

Talk of the “true, secret, hidden religious meaning” of “The 12 Days of Christmas” is pure hokum. It’s a collection of fabulously fabricated urban legends that have nothing to do with the actual song or its actual meaning.

But there’s also a true, secret, hidden religious meaning to our desire to know the “true, secret, hidden religious meaning” of ancient texts, and that turns out to be rather important. Understanding that can help us to understand the difference between reading and misreading — the difference between understanding and pretending to be people who understand.