The Harrowing of Hell is an odd “doctrine” involving an even odder word.

The idea was built out of and built on top of a smattering of strange phrases from scripture. For example, 1 Peter 3 says something about Christ being “put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit, in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison who in former times did not obey.” (I like Wycliffe’s translation there, describing these imprisoned spirits as those “which were sometime unbelieveful.”) To appreciate the oddness of that passage, note that the epistles of Peter also refer to Tartarus — the underworld of Greek mythology. And note also that this bit in 1 Peter 3 seems to be borrowing heavily from the apocryphal and dazzlingly weird books of Enoch.

By the time Christians got around to writing creeds, then, this had developed into the doctrine that Jesus — in between his execution and resurrection — had “descended into Hell.” This is the only mention of “Hell” in those creeds, and the Christians who wrote and endorsed the creeds at that time had a very different understanding of what that word meant than the Christians of a few centuries later who would elaborate and embellish that word into the basis for a wholly new doctrine borrowed from extracanonical sources even stranger than Enoch and Hesiod.

This can be confusing for 21st-century Christians because the word “Hell” can be traced back all the way to early Christianity, but the contemporary understanding of what that word means — both denotation and connotation — didn’t come around until much, much later. So we read the creeds talking about how Christ “descended into Hell” and we imagine they meant the same thing we understand when we see that word. This is a bit like someone reading Nietzsche’s references to the “superman” and interpreting that as him talking about Clark Kent.

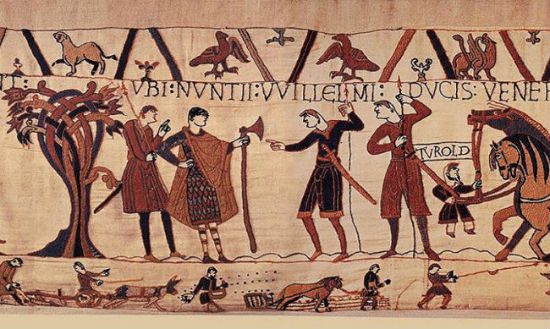

Anyway, neither of these “doctrines” — Hell or the harrowing thereof — really took off in the Christian imagination until visual artists got ahold of them. That brought about the earliest version of the art/doctrine feedback loop or the pop-culture/doctrine cycle we have now. The preacher talks about “Hell” and the artist is inspired to paint something loosely based on it. The next preacher’s description of Hell is based, in part, on that painting, thus inspiring the next artist’s creation. Lather, rinse, repeat. For centuries. Etc.

This process is still happening, which is why today, in 2018, when a revival preacher warns of “Hell,” he’s not just referring to the place — whatever it is — that the creeds say Jesus descended unto, but also to the place Dean Winchester descended unto. And that’s true even if neither the preacher nor his congregation ever watched Supernatural, because that preacher also never read “Paradise Lost” or “The Inferno” or the Gospel of Nicodemus or the Visión de Tundal. He and that congregation are certain that this word “Hell” refers only to a word they imagine comes from the Bible, but their understanding of that word comes from Milton, Dante, Bosch, Jack Chick, Dario Argento and, yes, even Eric Kripke.

All of which is to say that the “Harrowing of Hell” is — like “Hell” itself — better understood as Christian folklore than as Christian doctrine.

That’s reflected in the name for it — an English name. The English language — even the Old English from which we get this word “harrowing” — didn’t exist until centuries after the creeds first suggested something about Christ descending into Hell. The “doctrine” of the Harrowing of Hell didn’t flower into anything like its current state until after medieval English writers — and, more importantly, medieval English theater troupes — ran with it. That’s where we first get the idea that Jesus didn’t merely descend into the underworld, but that he “harrowed” Hell.

Odd word, “harrowed.”

Harrow doesn’t get used much anymore as a verb. It’s still quite often used as an adjective, though. We say something is “harrowing” to mean that it is distressing or painful in a deeply unsettling way — something that is not just agonizing but traumatizing. It leaves a mark, a deep groove that cuts below the surface. A harrowing experience is painful in a way that changes us.

This adjective still bears traces of the much-older verb and its Old English origins. To “harrow” meant to plunder or pillage. That had an analogical meaning related to the agricultural tool we still call a “harrow.” That’s a big frame with spikes or blades that can be dragged across a field to break up clods and weeds (or to smooth out the infield during the seventh-inning stretch). I’m not sure which meaning came first — whether what the tool did to soil was named after what invading armies did to villages or vice versa — but it’s easy to see how they are related one way or the other.

So, then, what was Jesus up to down there in the “Harrowing of Hell”? Whatever it was, the experience was harrowing for Hell — unsettling and traumatizing, leaving the place forever after scarred and wounded by it. Jesus, this odd story/folklore/doctrine says, plowed through the place, raking it to pieces, plundering and pillaging.

It reminds me of the scene in one of Wendell Berry’s Mad Farmer poems, when the farmer, drunk on communion wine, runs amok:

“It is an awesome event

when an earthen man has drunk

his fill of the blood of a god,”

people said, and got out of his way.

He plowed the churchyard, the

minister’s wife, three graveyards

and a golf course. …

I think the Harrowing of Hell should pay a bigger part in our thinking about the imitation of Christ. WWJD? He would harrow. And what would he harrow? Hell, and all its works. Harrow the principalities and powers, the rulers of the darkness of this world, the spiritual wickedness in high places.

We need to do a lot more harrowing. We need to make things more harrowing for those principalities and powers, those princes of Hell in all its forms. Break their big pieces into little pieces, carve out their weeds, pillage and plunder, proclaim liberation to the spirits in prison. Harrow, and harrow, and harrow some more.

And if we’re going to say anything at all about “Hell,” let it be what the creeds had to say. Hell was the thing that Jesus raked apart and plundered. Hell was whatever it was that found the healer harrowing.