Devin Powell grew up never expecting to graduate from high school. That had nothing to do with his particular academic prospects, it was simply that his family and his pastor did not believe that high schools, or the rest of the universe, would still exist by the time he was old enough to go. Evan V. Symon interviews Powell for Cracked: “6 Realities Of Growing Up Expecting The Apocalypse.”

Devin Powell was in middle school when his family packed up to await the 2011 apocalypse that evangelist Harold Camping had told America was coming. They had spent years preparing for the appointed date, and then, unless we missed something, the apocalypse did not in fact occur. What’s it like to spend your childhood assuming the world will end, only to have the rug not pulled out from under you?

I remember hearing Camping on “Christian radio” growing up. My family didn’t listen to him, specifically, but his broadcasts were carried on WAWZ, Zarephath, and I think he came on after Robert W. Cook. My mom loved “Dr.” Cook and often tuned in to his program while she was preparing dinner in our kitchen. She liked his kindly, encouraging preaching, but usually switched off the radio right after his signature sign-off — “Until I meet you once again by way of radio, walk with the King today, and be a blessing!”

Sometimes, though, she’d leave it on and we’d hear Camping or one of the other Family Radio preachers who, unlike Cook, tended to focus more on the Last Days and the End of the World. This was something my family believed, more or less. It was one part of the package deal of white fundamentalist Bible Christianity taught at our church and at the private Christian school we attended. And that package deal, remember, was all-or-nothing.

Our church wasn’t obsessed with the imminent Rapture, but it was built into our theology and worldview. It wasn’t something our pastor preached about regularly, but the ever-present possibility of an at-any-moment Rapture was often invoked — along with the Hypothetical Bus — to give altar calls a sense of urgency. And the church hosted occasional “Bible prophecy conferences,” multi-night events featuring guest preachers who would come in to teach about the signs of the times, and the generation that shall not pass away from when the End Times clock started counting down in 1948. We also watched A Thief in the Night and its sequels in our youth group. (I was young enough that the one with the guillotine gave me nightmares for weeks afterward.) Our Sunday school classes would occasionally feature series on “Daniel and Revelation.” I knew the charts, from Ironside to Hal Lindsey.

All of that gave me an advantage at Timothy Christian School, where we used Lindsey’s books as textbooks in high school Bible classes. I got straight A’s in that class.

At home, though, this End Times focus wasn’t a major emphasis of our faith. We believed it because it was part of the larger package we’d been taught we were supposed to believe, but we’d kind of shrug it off a bit by reflexively citing Matthew 24:36 — “But of that day and hour knoweth no man.” We frowned on “date-setters” and anyone so presumptuous as to claim that they had special insight into when The End was coming.

So my upbringing in the world of End Times Rapture Christianity was nowhere near as extreme as what poor Devin Powell describes. That’s true for most of us who were raised in that branch of the evangelical world. Camping’s failed 2011 “prophecy” was perceived, even by most Rapture Christians, as an extreme, exceptional aberration.

But still. …

No matter how cautious we might have been about date-setting and about “knoweth no man,” the general outline wasn’t really that different from Powell’s experience. When I first started high school, graduation seemed as unimaginably far-off as it did to any other freshman. We were the Class of ’86, and 1986 sounded like some exotic date from some distant science fiction future.

To the Class of ’86 at Timothy Christian, though, 1986 also seemed ominously close to 1988. That was a big date because 1988 was 1948 plus 40 years — 40 years being, as we were repeatedly told, a “biblical generation.” A core, non-negotiable, “biblical” belief we all shared taught us that the founding of the modern state of Israel in 1948 had started the final generation countdown, and that somewhere roughly around 1948 + 40 years was all that remained in human history before Jesus returned in the twinkling of an eye, followed by seven years of Tribulation and Antichrist guillotines. And then The End.

There was plenty of wiggle room in that. The 40-year generation was just a round-number estimate. And no man knoweth, not even the angels in heaven, etc. So we weren’t locked in on 1988 the way that Camping’s followers were later locked in on 2011. We were planning on college, after all, another four years of school. Would there be another four years? Maybe. Probably. We would be the Class of ’90 in college, and maybe there’d be a ’90. But a ’99? A 2000? That, we had been trained to believe, was less and less likely. A 2010 seemed almost impossible.

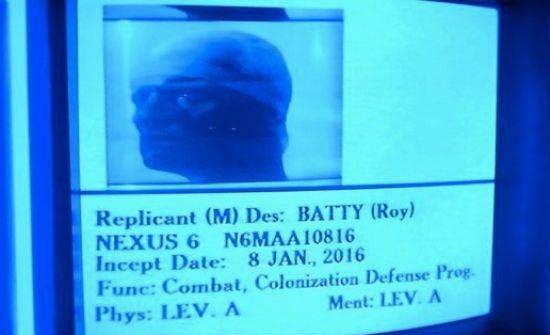

On one level, again, that wasn’t all that different from any other set of teenagers in 1982 when we were first starting high school. That was the year Blade Runner came out — a story set in the inconceivably alien world of the distant future of 2019. No 14 year old ever has a meaningful grasp on the idea that they and the rest of the world will still be around 30 or 40 years later.

But we had been taught to believe — and on some level we really did believe — that it wouldn’t be. That it couldn’t be. On some level we deeply, truly believed that neither we nor anything else would still possibly be around by now. That didn’t affect us as directly or as intensely as poor Devin Powell’s life was affected by his family’s certainty that the world was going to end on the specific date of May 21, 2011, but then, as devout little premillennial dispensationalist teenagers in the 1980s we would all have said — with equal confidence — that the Rapture was surely set to occur long before there ever would be a May 21, 2011. (2011 was 1948 plus 63 years and we could cite chapter-and-verse of Hal Lindsey to prove that we didn’t have that much time ahead of us.) “If the Lord tarries …” we would say, but there was no way the Lord was going to tarry that long.

It’s difficult, still, to fully understand how believing that affected us. It surely had some far-reaching, pervasive effects on our hopes and dreams and plans for the future. In part this was because it made hoping and dreaming and planning for our future seem impertinent — like a kind of betrayal of our faith and of the all-important package-deal that assured our eternal salvation.

That hints at what might be the deepest way this belief affected us. The fact that on some level we truly believed that our future was, at best, going to be very brief had to live alongside the fact that, on some level, we were incapable of believing this — that on some level we did not believe it at all. We spoke of future careers, of adult lives, of potential future children and grandchildren. And we also expected all of that the way everyone else did, as a matter of course. So the cognitive dissonance could be overwhelming.

There we were, the Class of ’86, as seniors at TCHS, cramming for our Bible midterms by studying flashcards of the “Bible prophecy” charts in Hal Lindsey’s books. Midterm exams were vitally important to us as high school seniors. You’ve got to do well if you want to get into college. But here was the very substance of what we were studying telling us that the world might very well not still be here by the time we got to college. Or by the time we got to finals, for that matter.

Yet we still studied. We were, in effect, training ourselves to believe and not-believe simultaneously. That’s not easy. It’s uneasy. It’s not sustainable in the long run.

As the years went by, and we came to see — contradicting all that we had so diligently studied and been taught to believe — that there was such a thing as a “long run” and as years going by, that cognitive dissonance became more acute. Something had to give.

For some, that was the entirety of the package deal construct of our faith. For others, it was the package-deal construct itself.

And for still others — like poor Harold Camping and his followers — it was the increasingly intolerable reality of reality.

The “Bible prophecy” racket has more than its share of cynical grifters, but I think Camping was a true believer. Think about what that came to mean for him, maintaining his state of peak imminence and expectation even as the years, and then the decades, rolled by. He started preaching about the imminent Rapture in 1958 and half a century later, in 2008, he was still at it. 1958 Harold Camping was certain — absolutely certain — that there would be no 2008 Harold Camping because he was certain there would never be a 2008. And yet there he was, his future self still preaching that there would be no future.

I think Camping just snapped. Back in 1958 he knew, with total certainty, that it was simply impossible the world would still be here by some time as inconceivably distant as 2012. And he knew that in 1968, and in 1978, and in 1988, and in 1998. And at some point it just all became too much and he snapped and set a date. He went all in, and he took thousands of his devoted followers with him.

Read that Cracked piece for a sense of how devastating that proved to be for those followers. (Camping died, broken and bewildered, in 2013.)

Their life-shattering and faith-shattering disillusionment was more extreme and more intense than what I and my TCHS classmates experienced, but it’s not entirely different. We went through something like it, just more gradually, and in smaller, more survivable portions.

Devin Powell’s story exposes the sheer cruelty of date-setting apocalyptic prophecy. But that cruelty exists, too, in the subtler, fuzzier, forms of Rapture-Christianity we learned from Hal Lindsey and from others at my church and school. Rapture-Christianity taught us, from a young age, that we had no future. That’s a horrible thing to teach a child.