“Deep movie emotions for me usually come not when the characters are sad, but when they are good,” Roger Ebert writes. “You will see what I mean.”

Those are the final lines of Ebert’s review of Hotel Rwanda, a beautiful film about an unlikely hero in the midst of unimaginable horror and evil. Ebert said something similar in his commentary for the DVD of Casablanca: “When I think about the kinds of movies that make me cry, that make tears come to my eyes, I usually don’t think about sad films. Sad films, I sort of just look at it. It’s movies that are about selflessness, that are about sacrifice, about humans that believe in the good of the human race that sometimes move me.”

Ebert said this, or something like it, quite a bit. See for example here too:

I’m often asked which movies made me cry. Without making a list (I hate lists of movies, which are so reductive), I’d have to reply that the deliberately sad films, the “weepies,” rarely make me cry. What gets to me are the films about goodness — about people acting bravely or generously or in self-sacrifice. … At the end of the day, films like these are what persuade me to be a film critic. My job is to call attention to them. They need not be so deeply serious, but they need to have that human generosity and goodness.

Most of that essay focuses on high-brow cinema — Schindler’s List and Bergman and Kurosawa, but Ebert concludes by saying: “If I were to say that even Juno belonged on the list, would you understand?”

Yes I would. Yes I do.

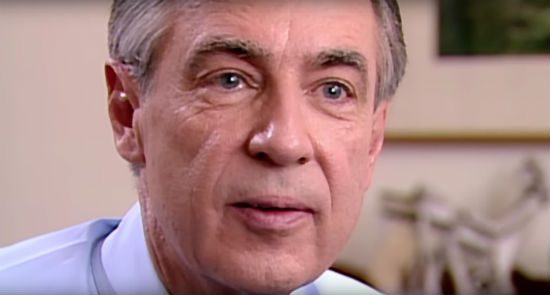

I was reminded of Ebert’s remarks this morning when I came across a discussion on Twitter of the recent documentary on Fred Rogers, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? I haven’t seen that yet, but just watching the trailer for it gets to me in just the way Ebert describes:

It’s been a hell of a week, one that many of us have spent wavering between heartbreak and white-hot rage. Both of those emotions are utterly appropriate and utterly necessary right now, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

That’s how some people will try to use the witness of a life like that of Mister Rogers. They’ll point to his unfailing kindness and gentleness and positivity and suggest that your hurt or anger is wrong — that you’re stuck in a bad attitude or some such rot.

But watch that trailer. There’s a bit in the middle where someone mentions Rogers’ “singular vision of kindness and love,” followed by title cards reading “See how a little kindness makes a world of difference.” And the whole thing seems on the verge of toppling into a saccharine puddle of goo. But then we hear from Rogers himself.

“Love is at the root of everything,” he says, in that gentle voice. “All learning. All relationships. Love or the lack of it.” And as he says those awful last four words, his voice changes from the tone he uses with children to the one he uses with adults. And you can see it all there in his eyes and his jaw and his face.

That’s 143 pounds of heartbreak and rage at a world far-too shaped by “the lack of it.” That heartbreak and rage was always there, not despite Rogers’ deep love, but because of it. Love always means this — it means taking on more than your individual share of pain and anger, because your love for others means making their pain and anger your own to whatever extent you’re capable of doing so. And Fred Rogers was more capable of doing that than most.

So heartbreak and rage are not the opposites of love; they are its evidence. Goodness and sadness aren’t always quite the opposites that Ebert’s observation makes them seem. Goodness tends to carry sadness — and anger — with it. But also joy. So there’s that.

In any case, at the end of a wrenching, enraging week, I need a bit of refreshment and I think perhaps Ebert’s consideration of movies — or scenes — that make us cry due to their portrayal of sheer goodness and humanity might be an energizing exercise and a bit of respite from the necessary work of all that heartbreak and anger.

Ebert’s right about lists, so instead of a list, let’s make a pile. A big heaping pile of movies or scenes (books and TV are fair game, too) that make our eyes fill up and our throats catch because they remind us that love is at the root of everything, and that we’re all also capable, too, of this.

I’ll start, please add more — many, many more, I need them — in comments. My all-time favorite such scene is probably one from a book, not a movie, but we’ll get to that in a couple of months as we do every year, so let me instead commend this scene from a movie. No one dies in this scene, no one gets hurt, but it gets to me every time because someone volunteers: