I’ve been thinking about Amber Wyatt for more than a week now. And praying for her, for whatever that’s worth.

In 2006, Wyatt was heading into her junior year at James Martin High School in Arlington, Texas. It should have been a great year for her, her first as a member of the varsity cheerleading squad, but that didn’t happen. Instead, at a party following a late-summer pep rally for the football team, she was horrifically raped, then shamed, shunned, and bullied out of school.

Elizabeth Bruenig tells Amber’s story in a remarkable, unsettling, almost unbearably heart-breaking Washington Post report: “What do we owe her now?” It is the awful story of a brutal crime compounded thereafter by an entire community responding by punishing its victim: “Twelve years ago, Amber Wyatt reported her rape. Few believed her. Her hometown turned against her. The authorities failed her.”

Bruenig is writing about her own hometown, her own high school. She was a year behind Wyatt at James Martin, didn’t know her, and didn’t travel in any of the same social circles (it’s a pretty big school). But like everyone else, she heard the rumors and the accusations, the lies and the blame and the ugly graffiti:

By the end of the fall semester, she had disappeared from our high school, leaving only sordid rumors and a nascent urban legend.

I never saw her, the rising junior-class cheerleader who said she had been assaulted by two senior boys after a party. I only heard about her. People whispered about her in classrooms and corridors as soon as school started that year. The tension in the school was so thick that the gossip about what had taken place trickled down even to the academic decathletes and debate nerds like me, the kids who could only speculate about what happened at the parties of athletic seniors. I was a 15-year-old rising sophomore, and even I formed a notion of what had happened, or what was said to have happened.

The next day, people whispered about the word in the halls. It was an acronym, I learned, meaning “f— Amber in the head,” or “f— Amber in three holes,” which I awkwardly explained to my parents when they asked me one evening why so many cars around town were thus marked. The idea struck me as brutally, unspeakably ugly, and it was the ugliness that came to mind each time I saw some rear windshield dripping the word in streaky chalk at the local Jack in the Box or Sonic Drive-In. Eventually I heard the girl had recanted her allegations and then had gone away; the writing on the cars, too, went away, and the question of what had happened that night.

But the question never went away for Bruenig:

I found it difficult, over the ensuing years, not to think about what had happened that August. … In April 2015, as a young writer, I was granted the rare opportunity to explore this notion. I was working at the New Republic magazine at the time, enjoying the warm auspices of an editor mostly content to let me pursue what I found most interesting. With his blessing, I reached out that spring to the girl whose name had appeared in acronyms and spray-painted slurs, and asked whether she was interested in talking to me about 2006.

Her name was Amber Wyatt, and she was.

On and off over the next three years, I reviewed police documents, interviewed witnesses and experts, and made several pilgrimages home to Texas to try to understand what exactly happened to Wyatt — not just on that night, but in the days and months and years that followed. Making sense of her ordeal meant tracing a web of failures, lies, abdications and predations, at the center of which was a node of power that, though anonymous and dispersed, was nonetheless tilted firmly against a young, vulnerable girl.

This is a remarkable, thoroughly researched, beautifully written, and powerfully honest piece. Bruenig’s determination and Wyatt’s courage are inspiring even as the content is, obviously, extremely disturbing. I urge you to read the whole thing if you are able, while also warning that doing so may be disheartening and derailing. Here, again, heartbreak and fiery rage will be unavoidable for any reader capable of love.

Spoiler alert: No one was ever charged for this crime. The victim was punished mercilessly, but the criminals themselves went on playing high school football and soccer. They graduated and went off to college, perhaps. They will never be held accountable for their actions.

As Bruenig explains in the excerpts above, she planned and worked on this piece for many years. It took three long years of work to produce an account of a 12-year-old crime and its aftermath, and last month, finally, once all of the research, interviews, writing and editing were complete, the final result wound up being published in late September 2018 — just after the first allegations against federal appeals court judge and Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh had become public, and just before the ugly spectacle of last week’s hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

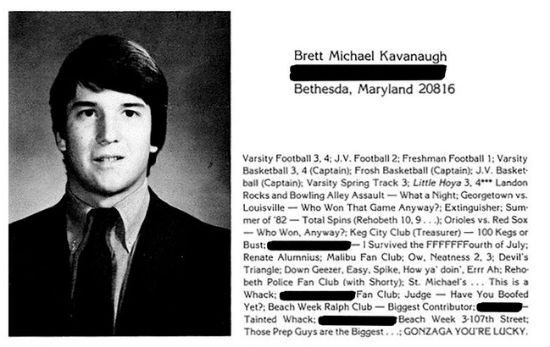

That coincidence of timing was stunning in part because the details of the 2006 crime that Bruenig recounts are remarkably close to the description of the 1982 crime at the center of last week’s Senate hearings. And the mindset of the teenaged criminals from 2006 is almost exactly like the mindset that Brett Kavanaugh was accused of having in some of the most luridly damning testimony presented against him. That was the testimony presented against him by himself by way of his own high-school yearbook entry.

It’s written in prep-school frat-boy slang from the 1980s, but multiple references in that yearbook entry correspond to and corroborate Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony about what she witnessed and was subjected to one night in the summer of 1982. They do so with a stomach-turning specificity.

This is why Brett Kavanaugh lied — extensively and repeatedly — about the meaning and content of that yearbook entry. He had to — inventing new and novel alternative meanings for the particular slang references to precisely what it is that he and his friend Mark Judge were accused of attempting to do. The same thing that a different set of frat-boy jocks, in a different state, did to another helpless girl in 2006.