• Here’s an illustration of what George Orwell was getting at in “Notes on Nationalism.” It’s an ugly story from Australia involving a politician groping a journalist at a Christmas party.

Like most Americans, I don’t know much about the current political alignment of New South Wales, so I have no idea whether this politician — the NSW Opposition Leader — is a conservative or a progressive or what. We don’t need to know that. That isn’t relevant or useful information for us when responding to this story.

But as Orwell says, we are all tempted or inclined to respond to this story through the lens of what he calls “nationalism” — to think we need to know whether or not the offending, offensive politician here is or is not a part of our team, and then to adjust our response accordingly. Don’t do that:

As for the nationalistic loves and hatreds that I have spoken of, they are part of the make-up of most of us, whether we like it or not. Whether it is possible to get rid of them I do not know, but I do believe that it is possible to struggle against them, and that this is essentially a moral effort. It is a question first of all of discovering what one really is, what one’s own feelings really are, and then of making allowance for the inevitable bias. If you hate and fear Russia, if you are jealous of the wealth and power of America, if you despise Jews, if you have a sentiment of inferiority towards the British ruling class, you cannot get rid of those feelings simply by taking thought. But you can at least recognize that you have them, and prevent them from contaminating your mental processes. The emotional urges which are inescapable, and are perhaps even necessary to political action, should be able to exist side by side with an acceptance of reality. But this, I repeat, needs a moral effort, and contemporary English literature, so far as it is alive at all to the major issues of our time, shows how few of us are prepared to make it.

• Netflix’s new Sabrina series provides the hook for Rosemarie Ho’s breezy roundup of several decades of Satan in American pop culture. I’ve got a quibble, though, with Ho’s introduction, in which she writes:

The newly released Netflix series Chilling Adventures of Sabrina is primarily about a half-mortal, half-witch named Sabrina trying to balance her responsibilities to both worlds. More interesting than the death and sex, however, is the explicit presence of Satan himself — the literal Biblical devil — as part of the undead choir urging Sabrina to accept her destiny as a witch and a servant of the Church of Night.

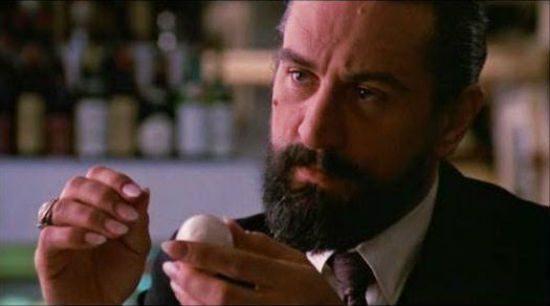

What the rest of the piece makes very clear is that “Satan” — as a character on Sabrina, or in Rosemary’s Baby, or in The Exorcist, or in the Satanic Panic, or in the pages of Charisma — has nothing at all to do with anything that can accurately be called “the literal [b]iblical devil.” This “Satan” character does not come from the Bible. He comes from … well, from Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist, and the fabulous lies of Mike Warnke, and now from Sabrina, too.

“Satan” has always been fodder for pop culture. But “Satan” also is, and always has been, a product of pop culture.

To the extent that there is any such thing as “the literal biblical devil,” it is almost impossible for us to see it or to identify it, because we cannot read the word “devil” without bringing to it and imposing on it two thousand years worth of art, storytelling, and pop culture. “I saw Satan fall like lightning from Heaven,” a Bible verse says, and whatever that verse originally meant or intended, it’s read by us to include Milton and Dante, Sandman and Screwtape, Charlie Daniels and Robert Johnson, Supernatural and Sabrina, Procter & Gamble and Mike Warnke.

And that’s true even for those of us who’ve never read or watched or listened to any of those.

• As for the Netflix show, I watched the first episode of the new Sabrina and found it surprisingly Baptist. Here is a TV show in which the central dilemma facing the central protagonist is whether or not she will be baptized and who gets to decide that. Is it up to her? Or is it predetermined (or predestined) for her by her family, or her family’s church, or by some higher power? It hardly matters that the “church” in the story is the (fictional and utterly not “literal biblical”) Church of Night, this seems to be a story about soul freedom.

Alas, that’s undermined somewhat by the genetic magic of the show’s mythology, with “witches” as a distinct race whose magic is a product of their bloodline. If you’re writing fantasy stories involving magic, don’t have it work that way. (Unless you want to spend part of your story either embracing or elaborately avoiding the problematic implications this will have in your world.)

• Terrific review essay in which Nathan J. Robinson admires Jill Lepore’s new history of America, but notices something rather large is missing. He recommends Erik Loomis’ A History of America in Ten Strikes as a remedy for that. From Loomis:

Most of us are not wealthy and will never be wealthy. We are workers, laboring for a few rich and powerful people, mostly white men who are the sons and grandsons of other rich white men. We have a hierarchical society that has used propaganda to get Americans to believe everyone is equal. We are not equal.

That paragraph is: A) generally regarded as impolite to mention; and B) undeniably true.

Also from that essay is a delicious quote from Cotton Mather that Lepore plucked out for her history: “The Plain Design Of Your Paper Is To Banter and Abuse The Ministers of God.” That was from Mather’s angry letter to publisher James Franklin. The contemporary heirs of Cotton Mather are still writing the same thing, but instead of Capitalizing Every Word they now capitalize every letter.