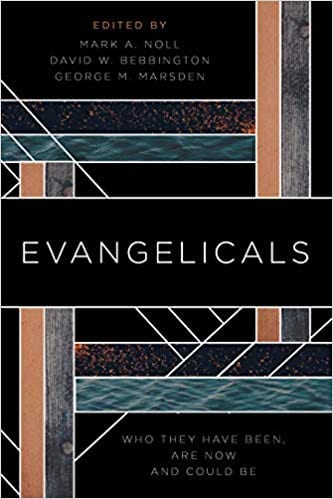

Evangelicals: Who They Are Now, Have Been, and Could Be is officially hitting bookstores today.

Well, it would be if bookstores were still a thing. Or if bookstores that carried semi-scholarly books from Wm. B. Eerdmans had ever been a thing.

But still, it’s an exciting day for a certain kind of niche library and the kind of folks who like such places. So Yay!

This book was put together by three top-notch, influential religious historians — Mark Noll, George Marsden, and David Bebbington. It includes some meaty contributions from all of them, plus a bunch of other good stuff from people like Molly Worthen, Kristin Kobes Du Mez, Jemar Tisby, Tom Kidd, and me. I’m anxiously watching the mailbox for my contributors copy so that — after shamelessly scanning my own chapter first, because of course I will — I can dive into the rest of the book to see what the editors have put together here.

This book was put together by three top-notch, influential religious historians — Mark Noll, George Marsden, and David Bebbington. It includes some meaty contributions from all of them, plus a bunch of other good stuff from people like Molly Worthen, Kristin Kobes Du Mez, Jemar Tisby, Tom Kidd, and me. I’m anxiously watching the mailbox for my contributors copy so that — after shamelessly scanning my own chapter first, because of course I will — I can dive into the rest of the book to see what the editors have put together here.

I’m pretty sure my part in this came about because my chapter includes a joke about George Marsden. It may not be the funniest joke about George Marsden, but it’s still probably in the Top 10 because, let’s face it, how many of those can there be? In any case, I’m grateful that the goodwill of that gentle joke apparently outweighed the fact that I’ve also posted lots of things with titles like “Bebbington schmebbington” or “The Hole in Noll.”

Like several of the other contributors to this volume, my interest in any “definition” of evangelicalism differs quite a bit from that of historians like Noll and Marsden and Bebbington. Their careers have involved writing about the history of this group of religious believers, and doing that required some kinds of definitions and boundaries to be clear about who their histories covered — this group of believers rather than that group. I’m more interested in the way “evangelicals” themselves have always used such definitions and boundaries to claim or assert power, and what they have used that power to do.

As Michael Altman, a religious studies professor at Alabama, recently put it on Twitter:

We need an account of how various definitions of “evangelical” and “evangelicalism” get constructed and to what ends they are deployed. … I don’t think we should use “evangelicalism” as a category for scholarly analysis. It’s a term that we should be analyzing not one we use to analyze with.

Amen.

That’s also why I often joke that the most useful “definition” of evangelicalism is “The set of white Protestant Christians who perceive themselves as solely and uniquely legitimate among white Protestant Christians.”

The problem there– as the great religion scholar Emo Philips reminds us — is that many different sub-sets of white Protestant Christians perceive themselves as solely and uniquely legitimate among white Protestant Christians. So are there, then, many different evangelicalisms?

Nah. Just the one. All of those fierce intramural disputes and exclusions and narcissisms of small differences are ultimately inconsequential when it comes to the one thing that unites all of those various and otherwise contradictory groups of white Protestant Christians: they all voted for Donald Trump.

But wait, you say, they didn’t all vote for Donald Trump — only 81 percent of them. True. But you know what they all think and say — loudly — about that remaining 19 percent? Hint: It’s right there in our kidding-on-the-square definition of evangelical. That 19 percent, they say, are not real, true evangelicals. They are not among the set of white Protestant Christians who are solely and uniquely legitimate.

We could ask if that’s true. Do “faculty lounge” types like the editors of Evangelicals, and all the contributors to it, and the folks at Eerdmans press, really qualify as legitimate members of evangelicalism?

But as Altman said, that’s the wrong question, one that will only confuse and mislead. It’s trying to use the term “evangelical” as a tool for analysis rather than recognizing it as something that desperately needs to be analyzed.