• It’s easy to get lost trying to draw lines between sincere culture warriors and the class warriors of the 1 percent. We could, for example, look for supposed differences between the Jerries Falwell, senior and junior, and project this distinction onto them. Jerry Sr. built an empire based on the culture wars — on fighting a white-fundamentalist backlash against “the 1960s,” while his son inherited that empire and turned it into a money-making machine, building a personal fortune of some $100 million while pursuing a life that shows little trace of his father’s purported piety.

But look a little deeper and you’ll find only differences in degree, not in kind. It becomes difficult, if not impossible, to draw lines between the culture-warriors and the class warriors.

But look a little deeper and you’ll find only differences in degree, not in kind. It becomes difficult, if not impossible, to draw lines between the culture-warriors and the class warriors.

Such would seem to be the case with Paige Patterson, the fiercely patriarchal architect of the “conservative resurgence” that transformed the Southern Baptist Convention. Patterson remains a hero for the Christian nationalist wing of the SBC (even if he is now an uncomfortably awkward standard-bearer for their cause due to his long history of covering up and compounding sexual abuse). But this long-time general in the culture wars also seems to be just another white-collar grifter fighting the class wars on the side of the 1 percent: “Baylor, Southwestern Baptist sue to wrest control from ‘rogue’ foundation with ties to Paige Patterson.”

The details alleged here are Trumpian and sordid.

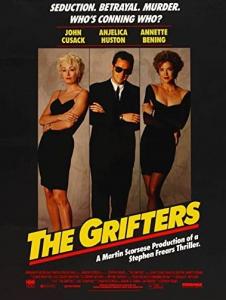

A wealthy donor died, establishing a foundation for the support of two schools. That foundation was taken over by Patterson and his cronies and now seems to function as a personal piggy bank for their benefit. It looks like your basic 1-percenter grift — the kind of brazen white-collar scam that lets those with fountain pens rob massive fortunes with impunity while Pretty Boy Floyd becomes “Public Enemy No. 1.”

• Speaking of Americana classics, the Smithsonian looks at “The Complicated Legacy of ‘My Old Kentucky Home’.” Stephen Foster was never quite able to tear up the letter and turn the raft around, but this song was maybe as close as he came to that. Think of this song as a sacred text and consider how the meaning of that text has been used for contradictory purposes, and how those uses have thereby changed the meaning of the song and even changed the song itself. It’s comforting to imagine that other sacred texts might be immune to that same dynamic, but I doubt that’s true.

• Right-wing radio host, Bonhoeffer cosplayer, and all-around Very Silly Man Eric Metaxas achieved something like Peak Metaxas after the Republican National Convention when he attempted to sucker-punch an anti-Trump protester. Metaxas, for some reason dressed like a cross between Thurston Howell and James Spader in Pretty in Pink, took an awkward swing at the passing bicyclist — a flailing left that glanced off the man’s shoulder — then pranced away as fast as one can in penny loafers. And it’s all on video.

Metaxas has expressed no remorse for his flaccid attempt at political violence, for his outfit, or for his attendance as a cheerleader at the illegal Trump pep rally conducted at taxpayer expense. The sad hilarity of this trivial incident has been enhanced by the fevered discussion of it on white Christian nationalist media, where critics of Metaxas’ shtick have been characterized as hippies and commies. (Messiah University historian John Fea was described as “a progressive evangelical,” while Warren “Too Hot for Patheos” Throckmorton was described as “left-leaning.”) That’s amusingly inaccurate, but not quite as revealingly misleading as this description of Metaxas-defending writer Rod Dreher, of “Lester Maddox Option” fame: “While some on social media, including at least one progressive evangelical thinker, have been critical of Metaxas in the wake of the video, evangelical author Rod Dreher appears to defend Metaxas …”

Dreher is not an “evangelical.” He’s not even a Protestant, although he was originally raised Methodist, he very publicly converted to Roman Catholicism in 1993 and then, in 2006, very publicly converted to Eastern Orthodoxy. Dreher is, however, a loyal Republican with a long history of disturbing statements and opinions about non-white people, so I can understand why the Christian Post writer mistook him for an evangelical.

• I do not wish to diminish concerns about academic freedom, etc., but there are also vital ethical questions about the morality of charging students tens of thousands of dollars a year to learn “philosophy” from a pretentious, pugnacious jerk who doesn’t seem very good at, or very interested in, philosophy.

• It’s likely that, like me, you do not have an intense interest in or passion about the obscure history of post-Roman Christianity in Britain. It’s also likely that, like me, you’ll find this recent post from Philip Jenkins fascinating because he does have such an intense interest and passion, and he makes it contagious.

• Elsewhere at the Anxious Bench, guest-blogger John Schmalzbauer looks at the history of church closings during pandemics, “Evangelist Billy Graham’s Granddaughter and Son Rail Against Public Health Measures Older Than Grandpa“:

North Carolina native Billy Graham was born a month after officials called for the closing of churches and schools. In October 1918, state health officer Dr. W.S. Rankin urged that “schools, moving picture shows, fairs, circuses and other public gatherings, including church services and Sunday schools be prohibited” under a 1911 law. With 8,000 influenza cases, the governor warned that North Carolina was “in the throes of the worst epidemic we have had for more than a generation.”

Church buildings closed all over North Carolina, including Steele Creek Presbyterian, the home church of Billy Graham’s maternal grandparents, and the place where his parents once worshipped. According to the congregation’s official history, indoor church was suspended for four weeks and “all services were held out-of-doors with people remaining in their automobiles.” In place of a pulpit, the pastor preached from the front steps or next to an open window, wearing a coat and hat. It is not clear if the closing order in nearby Charlotte applied to this congregation. It is clear that the church recognized the seriousness of an epidemic that killed eight members and sickened many others.