Today we’re joined at the Anxious Bench by John Schmalzbauer, a sociologist and professor of Religious Studies at Missouri State University who holds the Blanche Gorman Strong Chair in Protestant Studies. He is the author of People of Faith: Religious Conviction in American Journalism and Higher Education, and, with Karen Mahoney, The Resilience of Religion in American Higher Education.

We are in the midst of the worst public health crisis in living memory, with over 180,000 Americans dead from COVID-19. As cities and states struggle to contain the pandemic, two members of evangelicalism’s first family have taken a stand.

In a prime time speech at the Republican National Convention, Cissie Graham Lynch (the granddaughter of Billy Graham) portrayed state and local restrictions on public gatherings as an attack on religious liberty, complaining that “some Democratic leaders tried to ban church services while marijuana shops and abortion clinics were declared ‘essential.’” While acknowledging that “we have not faced physical persecution,” she noted “the left has tried to silence us,” adding that “during the pandemic, we saw how quickly life can change.”

In the days following the convention, Lynch’s father made a similar accusation. Asked whether America was at a spiritual crossroads, Franklin Graham spoke of “the changes that the left want to make and taking us into socialism is going to affect the church,” warning that the “government will begin to tell the church, how they can be the church, and they’ll close the church down in many places. We see right now, because of COVID, the government trying to tell the church that they cannot meet and the Constitution gives us that freedom to do that, but because of COVID, they said, ‘We can’t meet.'” Graham has also expressed his support for Baptist John MacArthur’s defiance of California’s closing order, calling it “an important stand for our religious freedom.” On August 1st, Graham encouraged his Facebook followers to attend MacArthur’s church.

While such rhetoric may play well on CBN or FOX, it is historically ignorant and medically irresponsible.

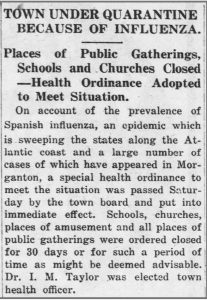

Far from a socialist plot, restrictions on public gatherings, including church services, are a legal and effective strategy for fight

ing disease, used most famously during the influenza epidemic of 1918.

Ironically, North Carolina native Billy Graham was born a month after officials called for the closing of churches and schools. In October 1918, state health officer Dr. W.S. Rankin urged that “schools, moving picture shows, fairs, circuses and other public gatherings, including church services and Sunday schools be prohibited” under a 1911 law. With 8,000 influenza cases, the governor warned that North Carolina was “in the throes of the worst epidemic we have had for more than a generation.”

Church buildings closed all over North Carolina, including Steele Creek Presbyterian, the home church of Billy Graham’s maternal grandparents, and the place where his parents once worshipped. According to the congregation’s official history, indoor church was suspended for four weeks and “all services were held out-of-doors with people remaining in their automobiles.” In place of a pulpit, the pastor preached from the front steps or next to an open window, wearing a coat and hat. It is not clear if the closing order in nearby Charlotte applied to this congregation. It is clear that the church recognized the seriousness of an epidemic that killed eight members and sickened many others.

Similar public health measures were enacted in 1920, as cases rose. On January 30th, the city of Asheville (near the future home of Billy and Ruth Graham) shut down. The mayor was a bank director, not a socialist. While the ordinance originally included churches (clergy complained), the city changed the church closing order to a non-binding resolution, respectfully requesting that congregations suspend all gatherings. Most stopped meeting.

After journalists questioned the legality of mandatory church closings, Judge George W. Connor told the Asheville newspaper that “no one has questioned the power of the board of health to pass the closing ordinances or the duty of all citizens to obey them.” Summing up the judge’s comments, the headline in the Asheville Citizen proclaimed, “Police Power Can Be Invoked to Close Churches in this State.”

These regulations were not unique to North Carolina. Here in the Show Me State, government closing orders led to the suspension of church services in October of 1918. Commenting on these restrictions, the Baptist publication Word and Way urged Missourians to cheerfully comply, telling readers, “Our people desire to be helpful in every possible way. So, of course, we will respect the requests and suggestions of the health authorities. But while closing our public places is in vogue, surely we can have worship in our own homes.” Two weeks after the closings, there was no cry of liberty lost or simmering resentment.

Such patience did not last. By mid-November, Missouri Baptists were chafing under the influenza ban, reporting that for a “full month now there have been no services in our churches throughout the state, and, of course, there has been little or nothing coming from the churches into the treasury of the Board.” Invoking the First Amendment, Word and Way noted that the “constitution of the United States recognizes the separate right of the worshiper of God to meet when and where he pleases to worship his Maker.” While agreeing “that it is all right and wise to have health boards, and the like, and that they should be clothed with authority,” Missouri Baptists were tired of meeting at home.

Back in North Carolina, the Charlotte Ministerial Association joined the fight against church closings, in a letter published on November 5, 1918, two days before Billy Graham’s birth. While agreeing that everyone should be “doing all that is possible to stamp out plagues,” the Association argued that “churches should not be closed until an epidemic becomes sufficiently dangerous and serious as to make it necessary to close such business where people gather in large numbers.”

Under pressure from both clergy and a group of local pool hall owners, the closing orders were lifted. The result was a spike in cases, whose full devastation has only now been revealed (see Mark Washburn’s groundbreaking account in the Charlotte Observer). According to Washburn, several hundred Charlotte residents died of influenza in 1918. Reflecting the epidemic’s impact on a local military base, nearly every train leaving Charlotte had caskets on board.

Like their early twentieth-century counterparts, the Grahams have sent mixed messages on public health. Early in the pandemic, Franklin Graham sent Samaritan’s Purse to provide lifesaving care in New York City. Back in April, Graham preached the importance of masks and social distancing, telling the Charlotte Observer that he planned to spend Easter Sunday at home.

Something changed between then and now. By endorsing John MacArthur’s mostly maskless church services and condemning restrictions on large religious gatherings, Franklin Graham is promoting behavior that could infect the vulnerable and lead to the loss of life.

He is not alone. Here in the Missouri Ozarks, faith communities have sent mixed messages on COVID-19. While a coalition of local faith leaders has expressed strong support for city and county health officials, debates about masking and social distancing too often feature hyperbolic claims about government tyranny and strained comparisons to Nazi Germany. Many are couched in the language of Zion.

By comparing public health measures to socialist tyranny and religious persecution, Franklin Graham and his daughter have weakened America’s response to COVID-19. It is not too late to repent.