What’s with the Mulder poster?

In the classic TV show The X Files, FBI Special Agent Fox Mulder had this poster hanging in his cluttered basement office. Mulder says he bought it in “a head shop on M Street,” but it was really designed for the show by series creator Chris Carter. (Ella Morton wrote a fine piece on the poster for Atlas Obscura. A copy of the poster is now in the Smithsonian collection.)

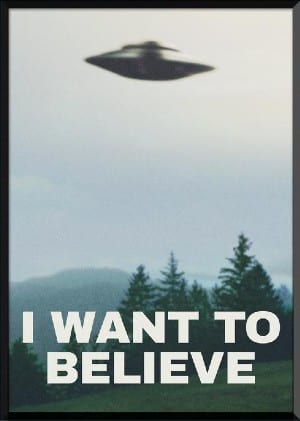

The poster appears, at first glance, to show a UFO — a 1950s-era flying saucer — hovering in the sky above a mountain range. Look more closely, though, and it looks fake (in some versions, you can see the string holding up the model). It’s a hoax, and not a very convincing one.

No one would consider the photograph in that poster to be valid evidence of extraterrestrial spacecraft visiting the Earth. If anything, the obvious fraudulence of the photograph would seem to be evidence that we should be even more skeptical of any such claim about UFOs.

No one would consider the photograph in that poster to be valid evidence of extraterrestrial spacecraft visiting the Earth. If anything, the obvious fraudulence of the photograph would seem to be evidence that we should be even more skeptical of any such claim about UFOs.

And yet, written beneath this clear fakery, in big block letters, are these words: “I WANT TO BELIEVE.”

Note what the poster does not say. It does not say “I BELIEVE.” It is not an assertion of belief, but an assertion of the desire to believe. So there’s an ambiguous irony to this poster. It might represent a kind of willful folly — a desire to believe so great that it’s willing to pretend the string isn’t there, clinging to an obvious hoax as though it were meaningful evidence to provide some pretext for the pretense of actual belief. Or it might, on another level, represent a commitment to finding the truth even in a world filled with hoaxes and deliberate misinformation — a skeptically open yet openly skeptical affirmation that “the truth is out there” and that we should follow that truth no matter how “out there” it might prove to be.

On The X Files, we first see that poster at the same time we first see Mulder, meeting both from the perspective of his brilliant, skeptical partner Special Agent Dana Scully and trying to figure out, along with her, which of those interpretations of that poster better described her spooky colleague. Is he someone so overwhelmed by his desire to believe that he’ll credulously cling to hoaxes? Or is he someone seeking truth beyond such hoaxes and despite them? That turns out to be a major theme of the show (which, admittedly, sometimes lost track of its themes, and its plot).

It’s a good show. At it’s best, it’s among the very best, and I thoroughly recommend it to anyone who hasn’t had the pleasure of watching it. But that’s not why I’ve used Mulder’s poster as a recurring motif here on this blog.

I started doing that back in 2008, using a knock-off freeware version of PhotoShop to replicate the poster with the former Procter & Gamble logo in place of the flying saucer. P&G had to change that logo — a key piece of the company’s long history — because of howlingly stupid and implausible rumors about the supposed “secret meanings” of its moon and stars imagery. Those claims about the soap-seller’s logo were tied to an even more outrageous and obviously false story about the company’s CEO (never named in this story) supposedly appearing on daytime television to declare his devotion to the worship of Satan.

Back in the late 20th century, when this story was spreading and circulating, such rumors were called “urban legends” rather than described as “conspiracy theories” or “fake news,” but it’s all the same thing. However we choose to label it, he two most astonishing facts about this P&G story were these: 1) It was patently, obviously, indefensibly false to such an extent that it was literally un-believable; and 2) Millions of people nevertheless claimed to “believe” it was true.

What could account for both of those facts? How had all of those millions of people — “good, Christian” people — managed to do the impossible and believe that which was unbelievable?

The answer, of course, is that they hadn’t. They did not “really believe” that story. No one ever could and no one ever did. Rather, they pretended to believe that story. They claimed to “really believe” and played along with that pretense, playing out the scenario of what such an impossible belief would entail.

The folly of that pretense was frustrating for Procter & Gamble and for anyone else who set out to spoil the game for them. It wasn’t possible to Scully them out of it with facts or logic or truth because, unlike Mulder, they were never true believers. It was just a game, one they had chosen to play and were determined to play no matter what all the spoilsports with their facts and truth and reality had to say about it.

This game-playing pretense of belief is not a consequence of misinformation, so any approach based on the idea of correcting misinformation would be useless. Nor was this game something people were “deceived” into playing. The lie of the story didn’t trick them or mislead them in any way, it simply invited them to play. And when they chose to accept that invitation, they agreed to participate in the deception — to become the deception. So any approach to them that treated them as people who had been deceived was also useless.

Over the years, I’ve badly PhotoShopped lots of other images onto Mulder’s poster, usually whenever I’ve encountered different variations of this same disingenuous game — this toxic, willful participation in deception presented as a pretense of “belief.” I’ve replaced that flying saucer with pictures of Mike Warnke, whose outrageous tales of Satanic baby-killing were also something that millions of good Christian folk also pretended to believe. I’ve pasted in the Pepsi logo to accompany a discussion of Christians who were pretending to believe that Pepsi was made from aborted babies. I redid the poster with pizza during PizzaGate and updated it to Q for QAnon — more recent variations of the same willfully perverse game of make-pretend.

And lately — because I’m lazy and, again, not good at PhotoShop — I’ve just settled on the explicit bluntness of replacing the fake spaceship with the words “Satanic baby-killers.” Because whenever people start playing this game, this pretense of belief as embodiment of deception, that’s always where they seem to wind up.

So that’s what’s with the Mulder poster. It’s what I fall back on whenever we encounter one of those stories that first makes us ask, “How do people really believe this stuff?” only to realize that the answer is they don’t.