It’s hard not to like Philip Yancey. After all, he seems to like you. And, in contrast to many other best-selling white evangelical authors, he seems to like God. That’s a major recurring theme in Yancey’s books and his long-running columns — the idea that God is worth liking because God is actually good.

That’s where this interview with Yancey from last week starts, discussing the “ungrace” of the “fundamentalist, rigid, legalistic” faith he was raised in. In that form of religion, God is not treated as someone or something good, but as someone or something “holy” and pure — so far beyond our human notions of goodness that God transcends, and contradicts, what we imagine as good. It’s hard to like such a God because, again, if God is like that — “good” only in a way that contradicts what we understand as goodness — then God clearly doesn’t like us very much either.

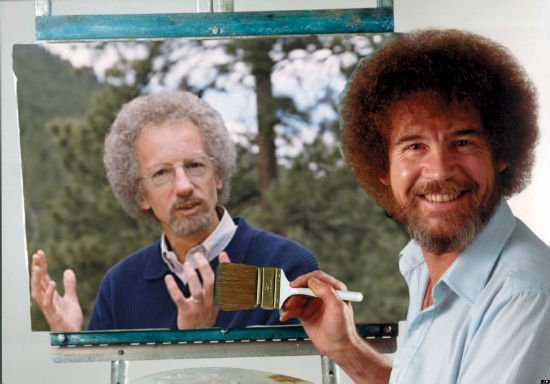

A while back, I slapped together this image of Bob Ross painting Philip Yancey as a disposable little visual gag about their hair, but it also illustrates something true about Yancey and his idea of God.

For Yancey, if God is God, then God must be at least as kind, patient, loving, and joyful as Bob Ross. If you’re redefining God’s “goodness” in a way that suggests God is less kind or less loving than the late Happy Painter, then you’re misunderstanding both goodness and God.

If you’re familiar with the arcane fights of the early church, you may recognize that in this line of reasoning I’m flirting with something some early church fathers fiercely — if unconvincingly — condemned as heresy. So let me be clear that Yancey himself never makes this argument in these terms. But I’ll gladly say it here: If you think God is less good than Bob Ross, then you’d be better of worshipping Bob Ross.

That is mostly a joke. But it’s a joke that invites us to imagine what our world might look like if the millions of our neighbors currently devoted to an unlikable God who doesn’t like us were, instead, gathering each week with their brushes and pallets and easels to paint happy little trees ad majorem Bob gloriam. That would certainly make for a very different world and, the more one imagines such a place, the more one has to admit it would likely be a better world.

All of which is to say, again, that I like Philip Yancey and I like his idea of God as a God who likes us and who is worthy of being liked.

But Yancey’s interview with Bob Smietana isn’t merely nice, it’s also thoughtful and thought-provoking — particularly this bit from the end:

So often the church seems more interested in cleaning up society, you know, returning America to its pristine 1950s. That’s the myth we have — we are making America pure again, cleaning it up.

Jesus lived under the Roman Empire, Paul lived under the Roman Empire, which was much worse morally than anything going on in the United States. They didn’t say a word about how to clean up the Roman Empire, not a word. They just kind of dismissed it.

So, why are we here? Well, we’re here to form the kind of community that makes people say, ”Oh, that’s what God had in mind.” We’re here to form pioneer settlements of the kingdom of God, as N.T. Wright puts it. It’s about demonstrating to the world what the whole human experiment is about.

This is a fine, winsome description of one tradition of Christian political thinking, one that attempts to sharpen Christians’ moral responsibility by emphasizing the boundaries of our political responsibility. Our responsibility, it says, is not to involve ourselves in this world’s worldly politics, but to create an alternative to that world by demonstrating the beloved community through our “pioneer settlements of the kingdom of God.”

The idea here is very much like the argument popularized by Stanley Hauerwas and Will Willimon in their books Resident Aliens and After Christendom. It’s an idea or ideal of Christian politics best embodied, perhaps, in the beautiful and inspiring example of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, the Huguenot Christian village in Nazi-occupied France where some 5,000 Christians sheltered more than 5,000 Jews. The exceptional story of that beloved community would be a powerful argument in favor of this alternative politics if it were not, alas, so very exceptional.

We could push back at Yancey’s description of Jesus and Paul as “dismissing” the Roman Empire by noting that this dismissive attitude was not at all reciprocal. And there are other critiques one could make of this longstanding, (sort of) apolitical view of Christian politics. But my point here is not to criticize this particular strain of Christian political thinking nor to merely categorize it a la H. Richard Niebuhr’s Christ and Culture.

What I want to point out, rather, is how this tradition — like most of our traditional strains of Christian political thought — fails to offer adequate guidance to Christians who are also 21-century American citizens. “Render unto Caesar” doesn’t correlate neatly to our context because, in a sense, or in theory — and in some ways tangibly more than just in theory — we are Caesar. We the people remain engaged in the “unfinished work” and the great experiment of living out some approximation of “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

That bit from the Gettysburg Address — delivered by a president who did more to consolidate and centralize the power of the federal government than any elected leader before or since — has always been regarded as more of a lovely bit of rhetoric than a meaningful description of reality. As I wrote several years ago:

That’sallwellandgoodintheory we rush to say, as good sophisticated cynics, but in practice it’s always been — and here we can insert any one of a number of popular competing critiques for why stuff is effed up and bullstuff and why representative democracy has never been representative nor democratic, etc. etc. That lofty phrase from the Gettysburg Address might as well be Patti Smith singing “The People Have the Power.” It’s all just naive hippy nonsense. (Patti was more punk than hippie, but, you know …)

And those critiques are not wrong, either.

But this savvy dismissal of the reality of “government of the people, by the people, for the people” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy — it becomes, in effect, a dismissal of the possibility of such a thing, an argument that puts such emphasis on the vast ways in which it has never been true that it winds up convincing us to abandon any efforts to make it closer to something true. This plays into the hands of authoritarians who do not want it to become true (and of their mindless lackeys who long to be ruled by actual Caesars).

Whether it’s the Hauerwasian strain of Christian political thought Yancey commends here, or it’s some variant of two-kingdom Lutheranism, or even the Neo-Confederate, Neo-Puritan white Christian nationalism of the religious right, most Christian political thinking has reinforced this anti-democratic, authoritarian tendency by failing to grapple with the possibility of Christian citizens as anything other than subjects of the governing authorities.

We need to do a better job of imagining what our responsibility entails if we allow ourselves to imagine that we the people are or could be, ourselves, those governing authorities.

See earlier: “Of, by, for” and “Romans 13 and the Gettysburg Address.”