• “All the people in the church were furious when they heard this. They got up, drove him out of the town, and took him to the brow of the hill on which the town was built, in order to throw him off the cliff. But he walked right through the crowd and went on his way.” — Luke 4:28-30

What had the mob in Nazareth so upset? Jubilee. Proclaiming good news to the poor and the year of the Lord’s favor. The forgiving of debts as we have been forgiven.

That invariably pisses some people off. But that’s OK. Those stunted, resentful people are telling on themselves — bragging about their incapacity to care about others. They are neither happy nor good and whenever they encounter happiness and goodness they want to drive it out of town and push it off a cliff.

Walk right through that crowd and go on your way.

Jesus chose not to waste any more time on people like that. He didn’t quite give up on them entirely — there’s a plate of fatted calf set aside waiting for them if they should ever choose to come in and join the party. But if someone prefers to manufacture bogus reasons for resentment and to prefer that resentment to grace and justice and jubilee and happiness … well, you can’t force them not to be like that.

Gratitude and ingratitude, crabs and buckets, clods and pebbles and olly olly oxen free. One way or another, it always comes back to Jubilee.

• Daniel K. Williams manages to discuss 20th-century white evangelical political allegiance without ever mentioning race, segregation, or the Civil Rights Movement: “It Wasn’t the Religious Right That Made White Evangelicals Vote Republican.”

Williams really, really wants to reassure himself that people like Randall Balmer are wrong about the central role that race and racism have played in shaping white evangelical politics (and, thereby, in shaping white evangelical religion). And so he embraces and accepts all of the coded language of the Southern Strategy, but treats it as good-faith, surface-level, naively innocent face-value references to red-blooded virtuous American values.

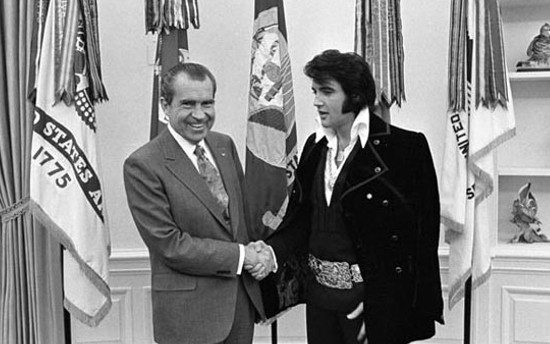

Why did white evangelicals support Nixon in overwhelming numbers in 1972? Williams says it’s because “opposed secularization and advocated returning a Protestant-style moral regulation to American politics to confront the sexual revolution and the cultural changes of the preceding decade.”

Ah, yes, “the cultural changes of the preceding decade.” Whatever might that refer to?

John Ehrlichman, after he got out of prison, frequently half-confessed and half-bragged about the way Nixon crafted his pitch to the white voters Williams discusses in order to make a racist appeal that would still (partly) allow such a voter to “avoid admitting to himself that he was attracted by a racist appeal.” It’s pretty wild to read the same euphemisms crafted by guys like Nixon, Ehrlichman, Lee Atwater, and Frank Rizzo employed as a defense against the charge that racism has ever had anything to do with white evangelical politics.

“The cultural change of the preceding decade.” Jeez Louise. May as well have just said that they had a principled dedication to states’ rights.

At Adventus, rmj responds to a similar claim about some pre-Trump innocence in white evangelical politics. He mostly does so by citing a contemporary primary source from the midst of “the cultural change” of the 1960s. It’s a passage that I have long argued should be regarded as biblical canon:

I have been disappointed with the white church and its leadership. … I do not say that as one of those negative critics who can always find something wrong with the church. I say it as a minister of the gospel who loves the church, who was nurtured in its bosom, who has been sustained by its Spiritual blessings, and who will remain true to it as long as the cord of life shall lengthen.

I had the strange feeling when I was suddenly catapulted into the leadership of the bus protest in Montgomery several years ago that we would have the support of the white church. I felt that the white ministers, priests, and rabbis of the South would be some of our strongest allies. Instead, some few have been outright opponents, refusing to understand the freedom movement and misrepresenting its leaders; all too many others have been more cautious than courageous and have remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained-glass windows.

In spite of my shattered dreams of the past, I came to Birmingham with the hope that the white religious leadership of this community would see the justice of our cause and with deep moral concern serve as the channel through which our just grievances could get to the power structure. I had hoped that each of you would understand. But again I have been disappointed.

That epistle affirms Williams’ secondary assertion that white evangelical reactionary politics was not created ex nihilo by Jerry Falwell in 1980 (which is also not an honest or accurate representation of Balmer’s argument). But it obliterates Williams’ larger claim that this politics has a centuries-long pedigree and, therefore, must be deemed innocent in its intentions and its effects.

The attempt to look back at two centuries of American white evangelical politics is daunting, in part, because it requires a constant category over time that has not, in any clear sense, been a constant category over that span of time. On that point I’ll just refer back to the Adam Kotsko piece that we discussed last month in which he notes that “[white] evangelicalism as we know it did not exist before the late ’70s,” clarifying in an impatient footnote provided for folks like Williiams that:

This claim may seem extreme. On the level of substance, however, it is impossible to understand contemporary evangelicalism as anything but a reaction to the counterculture of the 1960s. And on the level of style, it was only in the 1970s that the idea of a Christian counterculture — led, as always, by Christian music — really began to take off.

About which I wrote:

I think that’s right. White evangelicalism “as we know it” changed in both substance and style in reaction to the social upheaval of the ’60s just as surely as America as we know it did. (And, again, we should understand that “the ’60s” always means, primarily, the Civil Rights Movement and feminism, not the Beatles and Woodstock.)

• Also at the Anxious Bench, Philip Jenkins looks at the correlation between climate crises and plague, “These Are The Ways The World Ends.” It’s pretty grim, but it’s also fascinating:

Something very bad was happening around 2200BC, during what is called the 4.2 kiloyear event – that is, 4,200 years before the present. Far from being a transient episode, that great third millennium event – the snappily named “4.2ka BP” – is now acknowledged as marking a decisive shift in global climate. … It is quite conceivable that volcanic action or changing levels of solar energy might have been involved – or at least, something sufficient to transform the world’s oceanic currents. Just maybe, what about some extraterrestrial event, like a meteor impact?

We have one really infuriating problem here, in that we can easily find a very plausible candidate for the culprit, but the date as it stands just does not work. I am referring to the invaluable records preserved in the bristlecone pines of the US West. These map particularly severe years very effectively, and show us for instance that the globe was suffering particular horrors in 43BC, in the 530sAD, in 626AD, and other key dates. Almost certainly, the Something in question was some kind of volcanic action that darkened the skies, ruined crops, and induced far reaching famines. In these long biological arches, one date stands out very clearly as an utterly dreadful time to be alive, and that was 2036BC. It is a reasonable hypothesis that the trauma wrought on those Western trees was volcanic in nature, something at least on the scale of mighty Mount Tambora in 1815. If that was correct, it is scarcely surprising that civilizations would topple like dominoes. But in terms of explaining the collapses we have noted around the world, the date is just wrong, and it is off by two centuries.

Jenkins’ deep dive into the mysteries of the past is delightful. Or, I suppose, it would be if we had the luxury of studying all of this without also finding it urgently relevant. As Jenkins says, “The connection of climate-related disasters to plague, pandemic, and pestilence is very strong indeed. Understanding that dimension is vitally important for approaching our past, our history – but also, our futures, in an era of rapid climate change.”

• Here’s another track from Daniel Amos’ Buechner album Motorcycle. The title of this post comes from the lyrics to “Grace Is the Smell of Rain,” which, in turn — like most of the lyrics on this album — come directly or indirectly from Frederick Buechner.