From October 26, 2018, “Empathy and disgust are partners (‘I never asked you to have faith in me, Goody Watson’)”

It’s hard to make a living as a fortune-teller just from walk-ins. That may seem like easy money — a little cold reading, a little razzle-dazzle and you can pull in $50 or $60 an hour. But that only adds up if you’ve always got a line at the door, so if you’re gonna pay the bills, you’ll need regular appointments with return customers.

One common way to keep those customers/marks coming back is to delve into their unfinished business from past lives.

This is where the overlap between successful fortune-tellers and respectable academic historians comes in. Both occupations require a disdainful dismissal of, you know, all that Howard Zinn business.

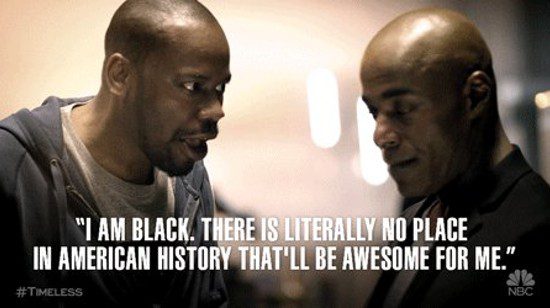

Your customers want to imagine that, in the past, they were Cleopatra, or Thomas Jefferson, or Stonewall Jackson, or Anastasia. They absolutely do not want to imagine the far greater odds that, had they lived in the past, they would have been some anonymous Egyptian slave or American slave or Russian serf. They’re not paying you to learn to be mindful of what life was like back then for most people most of the time, or even of what life is like for most people most of the time nowadays. They’re paying you to tell them they’re special.

So your fortune-telling, or your academic history lesson, requires a curated and circumscribed empathy. Extend that empathy beyond the short list of Very Special People your customers want to identify with and your sessions will gallop off into Rawlsian exercises in evaluation and judgment, bemoaning the staggering injustice of it all. And that’s not your job. Accurately identifying vast injustice as injustice isn’t how you make your living as a fortune-teller and/or academic historian. Nobody’s gonna pay you to hear that because, on some level, everybody already knows that and they’re trying not to think about it too much because they figure there’s nothing they can do about it anyway.

Your job, as a fortune-teller, is to provide them with the respite of an escapist fantasy that allows them to continue living with the existence of staggering injustice about which nothing can be done. I personally would not say that this is also your job as an academic historian, but a dismaying number of academic historians seem to arguing exactly that and I don’t want to upset them by disagreeing with them.

I’ve been reading, and therefore thinking, about disgust and empathy.

The links there are to two responses to Robert Orsi’s talk at the Conference on Faith and History, which seems to have made an impression. I now very much want to read it, even though reading it is clearly not a pleasant experience. It was, deliberately, a disgusting presentation.

“Disgust” was a theme in Orsi’s talk, as Elesha Coffman summarizes:

For many of us who attended the recent meeting of the Conference on Faith and History, the heaviest moments in a consistently weighty gathering came during Bob Orsi’s concluding plenary, “The Study of Religion on the Other Side of Disgust.” The address was rooted in his current research on clergy sex abuse in the Roman Catholic Church, and he spent at least 20 minutes recounting in excruciating detail the exploits of Father Paul Shanley, a predator whose superiors allowed him to abuse young people with impunity for decades. Not just allowed—empowered and paid by the church to run what one lawyer called a “pedophile paradise.” Why was Orsi, whose scholarly home is the American Academy of Religion, giving a plenary at CFH? Why was he telling us this appalling narrative? And what were we supposed to do with it?

Coffman responds to that talk by questioning the sufficiency — but not the necessity — of empathy:

I was trained to see the historian’s foremost ethical task as the cultivation of empathy. For years, I talked about this virtue on the first day of class. We historians, I used to say, “resurrect the dead and let them speak.” We listen to voices from the past humbly. We refrain from pronouncing anachronistic sentences on our fellow human beings who could not know what was coming next, and who did not have the benefit of whatever enlightenment we have gleaned since their passing. My white, male, Southern doctoral adviser used to say, “If I had been born in the early 19th century, I would have been a racist slaveholder, too.” Generations hence, our descendants will marvel at our blindness. Judge not, lest ye be judged.

That last bit is from Matthew 7:1. So let’s read the next few verses too: “For with the judgment you make you will be judged, and the measure you give will be the measure you get.”

The Bible is full of this sort of statement. See, for example, James 2:13, “For judgment will be without mercy to anyone who has shown no mercy.” As Richard Beck recently noted, “a strict, flat reading of texts like James 2.13 creates soteriological issues.” I would say it highlights those issues, rather than creates them, but he’s certainly right that such passages are a headache for abstract discussions of soteriology.*

But, as Beck goes on to say, “theology can be a distraction.” The main thrust here — as it often is in both the Sermon on the Mount and the book of James — is not soteriological, but ethical:

… from a daily, pragmatic point of view it’s a very clarifying perspective upon how to live and make choices today. … When I’m faced with the choice of extending mercy, sometimes you just need James 2.13 to give you a very clear word: Judgment will be merciless to one who has shown no mercy.

Theology aside, that sentence helps you make better choices.

What Beck and James here call “mercy” might be tucked into Coffman’s discussion under the umbrella of “empathy.” So it seems to support Coffman’s advisor’s “empathetic identification with slaveholders.” We are obliged to show them mercy, “for with the judgment we make, we will be judged, and the measure we give will be the measure we get.”

But that’s only Matthew 7:2. This little passage doesn’t end there. Here is the rest of this little pericope:

Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye? Or how can you say to your neighbor, “Let me take the speck out of your eye,” while the log is in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbor’s eye.

The point, again, is not soteriological or abstractly theological in any sense. It is explicitly about “a daily, pragmatic point of view.” It is about the fact that everyone’s point of view — everyone’s view — is hindered because we’ve all got all this crap in our eyes.

And the whole point here is to get all the crap out of everyone’s eyes.

Note that these verses, Matthew 7:3-5, instruct, command, and advise us to do the complete opposite from what 90 percent of the sermonizing and moralizing we hear about Matthew 7:1 suggests. Jesus is emphatically not saying “Judge not, and thus learn to forgive the speck in your neighbor’s eye so that, in turn, your neighbor will forgive the log in yours.” Ugh, no. Jesus says “take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbor’s eye.”

Take. Them. Out. Fix the problem. That requires us to identify the problem. And that requires us to make judgments, because only by doing that can we realize that the problem is a problem.

Of course we can’t be certain of our judgments or of our perceptions. They’re bound to be flawed because, again, we’ve all got all this crap in our eyes. So we need to be humble and merciful about it. Humility and mercy, though, are not the same thing as irresponsibility. What matters is the responsible recognition of that proverbial truth: “the measure we give will be the measure we get.”

That can be seen as a kind of corollary to the Golden Rule. Treat others the way you would have them treat you. When you “judge” others, you should also judge yourself by the same standards. You might as well — because the standard you use to judge others is the same standard everybody else is therefore going to apply to you. (And “everybody else” here includes God.)

John Fea’s response to Orsi’s presentation focuses on the task of a historian, and he notes that history is not studied or written for the same purposes as the Sermon on the Mount. It’s not primarily ethical. “The best historical works, and the best historical classes,” Fea writes, “are those that tell the story of the past in all its fullness — good and bad — and let the readers/students develop their ethical capacities through their engagement with it.”

When we let something like “disgust” drive our study of history, the history classroom turns into an ethics or moral philosophy classroom. At my institution, students take a course in ethics with another professor who is trained in the field. My responsibility is to teach them how to think historically — to walk in others’ shoes and try to understand the “foreign country” that is the past.

Yes. But which others’ shoes?

There’s the rub. And there is the shortcoming implicit in Coffman’s advisor’s otherwise wise advice to remember that “If I had been born in the early 19th century, I would have been a racist slaveholder, too.” His humble recognition based on empathy for those 19th-century racist slaveholders puts him at risk of failing to show the same empathy toward enslaved people in the 19th Century (a vastly larger category of people). Empathy for Fr. Shanley cannot be allowed to preclude empathy for his young victims. Showing the same degree of empathy to everyone involved in history requires the possibility of disgust — of anger, condemnation, judgment.

I’ve already tipped my hand by speaking of the requirement of empathy as necessary, but not sufficient. I would say the same is true of disgust. It’s not simply that one without the other would be incomplete, but that either one without the other is not a true version of itself.

This is why I don’t think it’s helpful to see disgust and empathy as opposites, or even as opposed. They’re often intimately connected — as in “Oh, jeez, if you ever see me doing something like that just shoot me.”

That’s a less pious, colloquial way of saying something similar to “There but for the grace of God go I.” The specific grace it invokes and offers thanksgiving for is the grace of good friends. It suggests that you, as my friend, are someone I can and do rely on to keep me from becoming “something like that.” As such, it extends pity toward the person or behavior being judged, recognizing that it is, in part, a consequence of their circumstance. That poor soul apparently does not have the sort of good, reliable friends who could and should prevent them from behaving like that. This statement also acknowledges empathy as the source of that pity — implicitly recognizing that I, too, might very well become the sort of person who might do such a thing were it not for the fact that I have better and more reliable friends.

The judgment requires empathy and the empathy requires judgment. Recognizing the necessity of both allows us to maintain the humility that we might have done the same awful things or been blind to the same in-your-face injustices if we had been in those other people’s shoes, but also to maintain the reality that it would still have been shameful and disgusting for us to have done so. Maintain, in other words, the recognition that we are all — I am — eminently capable of being disgusting. (Step two: Understand that most of us, in all likelihood, are doing or not doing something right now that merits disgust.)

For a reminder of what both judgment-without-empathy and empathy-without-judgment can produce, let’s turn again to the 23rd chapter of Matthew, just a few short pages after that whole “judge not” bit:

Woe to you, scholars and pastors, hypocrites! For you build the tombs of the prophets and decorate the graves of the just, and you say, “If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets.” … Fill up, then, the measure of your ancestors. … I send you prophets, sages, and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your churches and pursue from town to town, so that upon you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth.

The hypocrites Jesus is denouncing there were congratulating themselves for condemning their ancestors while simultaneously repeating the exact same behavior. Such hypocrisy is always the result when we’re focused on reassuring ourselves that we’re better than instead of focusing on just trying to be better.

For a wise, more contemporary version of this warning, let me again recommend this classic Toast piece: “Reasons I Would Not Have Been Burned As A Witch In The Early Modern Era No Matter What I Would Like To Believe About Myself And Would Have In Fact Been Among The Witch-Burners.”

I heartily recommend this to all historians as a supplement to all of those weightier, more intentionally philosophical essays on the duty of empathy and whatnot. It covers the same ground while also being much funnier. And shorter.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

* All universalists are saved! Oh, but wait, wouldn’t this mean that only universalists are saved? And wouldn’t that also mean that anyone who acknowledges that would therefore cease to be a universalist? And therefore …

Soteriology is no way to spend your life, kids. Matthew 16:25 and all that.