Today we’re happy to welcome back Elesha Coffman, one of Beth and Philip’s colleagues at Baylor University. Elesha previously wrote at Anxious Bench about her current research subject, Margaret Mead. Here she shares her reaction to a particularly challenging address from this month’s meeting of the Conference on Faith and History.

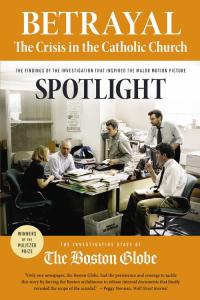

For many of us who attended the recent meeting of the Conference on Faith and History, the heaviest moments in a consistently weighty gathering came during Bob Orsi’s concluding plenary, “The Study of Religion on the Other Side of Disgust.” The address was rooted in his current research on clergy sex abuse in the Roman Catholic Church, and he spent at least 20 minutes recounting in excruciating detail the exploits of Father Paul Shanley, a predator whose superiors allowed him to abuse young people with impunity for decades. Not just allowed—empowered and paid by the church to run what one lawyer called a “pedophile paradise.” Why was Orsi, whose scholarly home is the American Academy of Religion, giving a plenary at CFH? Why was he telling us this appalling narrative? And what were we supposed to do with it?

I can only speak of my own reaction. For me, this was a painful but necessary step in moving away from my own scholarly formation toward something that feels more true in our historical moment.

I was trained to see the historian’s foremost ethical task as the cultivation of empathy. For years, I talked about this virtue on the first day of class. We historians, I used to say, “resurrect the dead and let them speak.” We listen to voices from the past humbly. We refrain from pronouncing anachronistic sentences on our fellow human beings who could not know what was coming next, and who did not have the benefit of whatever enlightenment we have gleaned since their passing. My white, male, Southern doctoral adviser used to say, “If I had been born in the early 19th century, I would have been a racist slaveholder, too.” Generations hence, our descendants will marvel at our blindness. Judge not, lest ye be judged.

That’s all true. But it isn’t enough.

I’ve grown increasingly uncomfortable with this elevation of empathy as I’ve become more, well, disgusted with the religious tradition (white evangelicalism) in which I was raised. A future white, evangelical historian could look back and say, based on 81% evangelical support for Donald Trump, “If I had been voting in 2016, I would have voted for Trump, too.” While statistically correct, that facile statement negates all of the incisive criticism of Trump, the impassioned opposition to him, the many things he has done that should provoke disgust in any observer. Similarly, my advisor’s empathetic identification with slaveholders negates eloquent spokesmen such as Frederick Douglass, the emotional appeals of abolitionists, and natural revulsion to the sight of bodies whipped and babies torn from their mothers.

Yes, we modern folk with our smartphones and social media have access to far more information, from more diverse perspectives, than our ancestors 200 years ago. But still. Many if not most of them could have known better. They could have done better. They chose not to.

I believe that Orsi walked us along a bruising pilgrimage through the archives to demonstrate that his disgust was not cheap judgmentalism. It was deep, and it was earned. When he built upon this disgust to declare that clergy sex abuse is not a “crisis” but is the modern Catholic world, and that “there is more to religion than this, but there is no religion without this,” even the members of his audience disinclined to share his brutal assessment could not dismiss it.

After Orsi’s address, we listeners staggered to the refreshment break, dazed. As I chatted with a knot of other female scholars, I mused, “Is disgust a necessary corrective to empathy? Does it redirect our empathy from abusers to the abused? Is it possible to empathize with human beings who suffered as we will never suffer—or was it ever really possible to empathize with people from the past at all?” We washed down our baffled rage with coffee and cookies. We had no answers.

Because the conference was held at Calvin College, I’ll credit Providence with guiding me to a final paper session where I heard Timothy Fritz speak on “Lament as Engagement: Teaching Histories of Slavery amid Contemporary Ecumenical and Ethnic Divisions.”

“When we don’t have words to say,” Fritz told us, “the psalms speak for us.” Specifically, he meant the psalms of lament, which constitute a significant portion of the psalter but are rarely used in worship in any Christian tradition. These psalms, he said, are framed by acknowledgements of God’s goodness but dwell with the suffering and do not hesitate to condemn the nations. Lament calls us to recognize what should not be. This profound theological insight can also be used pedagogically, in the context of Christian education, to guide traumatized students through devastating material. I hope that Fritz publishes a version of his paper, because I need it.

I don’t know yet how the arc of empathy, disgust, and lament will inform my teaching or scholarship. What I do will change, though, because I have been changed.

For two other responses to Orsi’s talk, see Mark Correll and Matt Stewart’s contributions to last Wednesday’s CFH 2018 post.