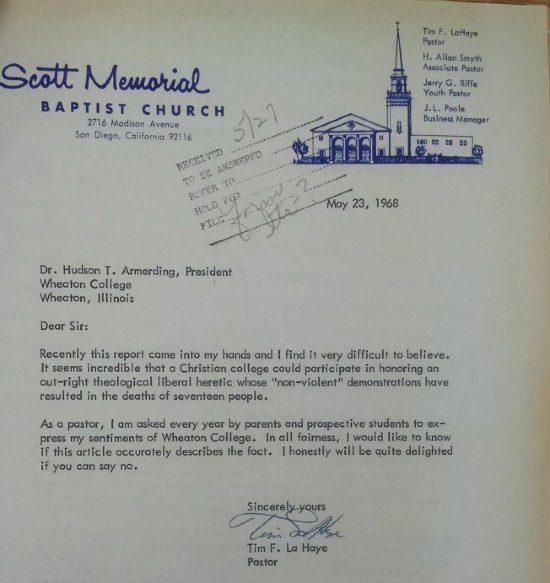

Jemar Tisby reminded us of this on Twitter on the MLK holiday last week, so let’s take another look at Tim LaHaye’s letter to Wheaton College from May 23, 1968.

For those who can’t read that image, here is the text of LaHaye’s letter:

Recently this report came into my hands and I find it very difficult to believe. It seems incredible that a Christian college could participate in honoring an out-right theological liberal heretic whose “non-violent” demonstrations have resulted in the deaths of seventeen people.

As a pastor, I am asked every year by parents and prospective students to express my sentiments of Wheaton College. In all fairness, I would like to know if this article accurately describes the fact. I honestly will be quite delighted if you can say no.

Those two paragraphs consist of three parts: 1) The pious performance of sanctimonious dismay and lamentation, which is the standard form for the angriest expressions of white evangelical condemnation; 2) LaHaye’s evaluation of the life, work, and faith of Martin Luther King Jr., who serves here as a representative of the entire Civil Rights Movement, and LaHaye’s implication that this evaluation is and ought to be the mandatory response to MLK/CRM from every legitimate white evangelical; and 3) an explicit threat to punish Wheaton College if it does not repent of memorializing King and quickly get on board with LaHaye’s denunciation of him and of the entire Civil Rights agenda.

It’s an ugly, shameful piece of work.

The “report” LaHaye refers to was likely some newspaper mention of the “community-wide memorial service” held at Wheaton on April 7, 1968, three days after King’s assassination. It might have been the Chicago Tribune article mentioning that service that John Fea posted last year in discussing LaHaye’s letter. This was long before the internet, remember, so it would’ve taken a great deal of time and effort for the network of Citizens Councils concerned white evangelicals to have gotten this report all the way from Chicago to LaHaye’s church in San Diego. They took that time and effort because “this report” was, to them, too alarming to ignore.

It’s perhaps not entirely accurate to describe Tim LaHaye as an “evangelical” back in 1968. At that time he would still probably have preferred the term “fundamentalist,” perhaps even insisting on that distinction as a badge of honor. LaHaye was a Bob Jones University graduate, after all, and one who agreed with Jones’ assessment that “an evangelical is someone says to a liberal, ‘I’ll agree to call you a Christian if you agree to call me a scholar.'” The term “evangelical” was still regarded as a shortening of “Neo-Evangelical” — a category deliberately created by folks like Billy Graham and Carl Henry to carve out a distinction between them and fundamentalists like Bob Jones and Tim LaHaye. LaHaye didn’t disagree with that distinction in 1968, but he resented it.

That’s what makes the pious preamble of his letter so transparently disingenuous. He doesn’t find it “very difficult to believe” at all. Wheaton’s memorial service, in his mind, proved that those squishy intellectual Neo-evangelicals were guilty of just exactly the sort of pseudo-liberal, Christian-in-name-only sins that he’d always accused them of.

That’s what makes LaHaye’s unsubtle threat seem strange. “As a pastor,” he says, “I am asked every year by parents and prospective students to express my sentiments of Wheaton College.” But he knows that Dr. Amerdling already knows what those sentiments are, and that there’s no chance of improving them. Parents and prospective college students at Scott Memorial were already being warned to stay away from dangerously “liberal,” not-really-truly-Christian schools like Wheaton. Those kids were all being sent off to Bob Jones, never to Wheaton, so there was no Scott Memorial-to-Wheaton pipeline for him to threaten to cut off.

The threat here — in terms of “parents and prospective students” — is really that LaHaye might switch from implicit, passive disapproval to explicit, active condemnation, singling out Wheaton as a pariah and punching bag. He could use his influence to create negative connotations of “controversy” and “liberalism” that could shape the perceptions of parents and churches beyond his own Southern California white fundamentalist networks.

Wheaton’s memorial service and LaHaye’s response to it recall a conversation between John Fea and Adam Laats that we discussed here several years ago. Fea, a history professor at a Christian university, sees the faculty and the students of a school as the locus of that institution’s character and identity. Laats, who teaches at a public university but focuses his research on religious schools, sees the administration, trustees, and donors, as the main actors shaping that identity and character. We can see the tension between those two sources of identity in this 1968 example, with Wheaton’s students and faculty responding to the assassination of King by organizing a memorial service to grieve and to honor the slain prophet while Wheaton’s administrators wound up responding, instead, to angry letters like this one from LaHaye.

Laats’ description of the mindset of those administrators helps to illustrate the seriousness of the threat Tim LaHaye was making to Wheaton’s president:

However the boundaries of evangelicalism are defined, whether in 1935, 1963, or 2016, schools need to remain squarely within them. More relevant, they need to be seen by the evangelical public as remaining squarely within those boundaries. If school administrators fail, students and alumni will vote with their wallets, taking their tuition dollars and donations elsewhere. …

Every school has certain poorly defined lines that no one is allowed to cross. Or, to be more precise, it means that the evangelical public needs to feel confident that the school as a whole is not crossing those lines, even if some students and teachers are. Or are rumored to be. …

… In short, to thrive and survive, evangelical colleges need students. To attract students, leaders know their schools must be perceived as safe evangelical environments.

Honoring Martin Luther King Jr., LaHaye said, meant legitimizing the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. And if Wheaton were to suggest that the Civil Rights Movement was legitimate, then he would declare it anathema — outside “the boundaries of evangelicalism” and no longer to “be perceived as a safe evangelical environment.”

Laats mentions wallets and donations. LaHaye’s doesn’t explicitly refer to donors in his letter because he didn’t need to, but this was also a big part of the threat he was making.

The image of LaHaye’s letter above comes from a blog post by historian Jesse Curtis’ in 2017. Curtis lists a series of questions raised by this letter as an artifact from Wheaton’s archives. He asks, for example: “Did the blowback Wheaton received (this was only one of dozens of letters) affect its institutional behavior in subsequent years?”

That’s an interesting question, and I’d be interested in seeing it addressed by someone who’s familiar enough with that “institutional behavior in subsequent years” to answer it. I’m not that someone.

I am, alas, someone who is depressingly well-prepared to address the questions Curtis raises about Tim LaHaye:

What kinds of information did LaHaye rely on to understand the civil rights movement, and where did the “deaths of seventeen people” statistic come from? Was this a right-wing meme? How did it circulate in this pre-internet age? Did LaHaye blame Dr. King for all the violence that occurred at his protests?

Was LaHaye satisfied with the president’s reply? (There is no subsequent letter from LaHaye in the archive.) Did he continue to recommend Wheaton College to his congregation?

Did LaHaye change his views in later decades? As memory of the civil rights movement changed and it became impolitic to have such a negative view of Dr. King, did LaHaye adjust, or did he just become silent?

Did LaHaye ever write anything publicly about the civil rights movement, or about race more generally? …

What does this reveal about the theological and racial climate of white evangelicalism in the late 1960s? Were LaHaye’s attitudes exceptional, or normal?

The answer to the first four questions is that LaHaye was a member of, and an ambassador for, the John Birch Society. Which is why the answer to the next two questions is “No.”

No, he was not satisfied with the president’s reply — whatever that was — because the Bircher’s whole thing was to be perpetually aggrieved and thus never satisfied with any reply, response, or concession. And no, he did not “continue to recommend Wheaton” because he had never done so previously. A few years later he started his own school — Christian Heritage College.

And that right there — “Christian HERITAGE College” — answers Curtis’ next three questions about the non-evolution of LaHaye’s views about the Civil Rights Movement. (While there do exist scattered examples of usage in which the word “heritage” is not a winking euphemism for white hegemony, this is not one of those examples. Again: John. Birch. Society.)

Curtis’ final two questions there seem to require a book-length answer, but let’s focus just on that last one: “Were LaHaye’s attitudes exceptional, or normal?”

Tim LaHaye was asking that same question in 1968. He was fairly confident that his view was normal, and he was absolutely certain that it ought to be normal. But news of that Wheaton memorial service had him worried that some of his fellow white Christians weren’t holding the line. He fired off this letter to exceptionalize what he saw as Wheaton’s dangerous attitude, to ensure that any sympathy toward or respect for the Civil Rights Movement would be buried with that “liberal heretic.”

This is the key point about LaHaye’s letter. It wasn’t a one-off. On May 23, 1968, he wrote this letter aiming to delegitimize the Civil Rights Movement and to make opposition to the Civil Rights Movement a mandatory, necessary stance for all white evangelicals and fundamentalists — a defining boundary of evangelicalism. He went on to write more than 80 books, founded a university, and helped to launch the Moral Majority, Concerned Women for America, the Council for National Policy, the American Coalition for Traditional Values, the Coalition for Religious Freedom. And, of course, he teamed up with Jerry B. Jenkins to give us Left Behind.

All of that could be described as Tim LaHaye’s attempt to ensure that the attitudes he expressed in that 1968 letter would be and remain “normal” for white evangelicalism in the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, 2000s and 2010s. For the next 48 years of his life, right up until his unraptured demise in 2016, Tim LaHaye never stopped writing this letter.