I’ve never been really into the band Blue Öyster Cult, but thanks to my RSS Google News feed for the word “Satanic,” I wound up reading Sleazegrinder’s long, affectionate profile/history/tribute on Louder, “With lyrics by gonzo rock critics and a crazy live show, Blue Öyster Cult were born to break the mold.”

Sadly, the article never explains the unnecessary, but trend-setting umlaut in the band’s name — although maybe it does, indirectly, since the theme of this piece is the sometimes blurry gap between outrageous rock-n-roll mythmaking and reality:

The truth is almost comically anticlimactic. Blue Öyster Cult were not warlocks or space bosses or even backyard Satanists, they were engineering students and fantasy-novel readers from upstate New York who started their musical lives together as a jam band called Soft White Underbelly in 1967. Hippies, really, but hippies with vision – and two hotshot, first-generation gonzo rock writers scribbling endless pages of freaky lyrics for them.

Those two writers — Richard Meltzer and Sandy Pearlman — didn’t just supply lyrics, they also helped to manage the band, creating legendary personas for its members and spouting out a stream of publicity materials full of over-the-top impossibilities. This leads to my favorite anecdote in the piece:

“Sandy and Richard were writers, so to help promote us they’d make up shit about us.” Bloom says. “Meltzer wrote an apocryphal article about us in some rock magazine that was totally tongue in cheek. He wrote that we played at the Mount Rushmore rock festival. Of course, there was no such thing. But he said that the highlight of the show was when Eric Bloom jumped off of George Washington’s nose. A couple of years later, we’re driving somewhere in America in our van. We see some poor guy hitch-hiking on a two-lane blacktop, so we picked him up. ‘Are you guys a band?’, he asks us. ‘Yeah’, we tell him: ‘We’re Blue Öyster Cult’. The guy says: ‘No kidding! I was at the Mount Rushmore festival!’ He said he saw me jump off the nose…”

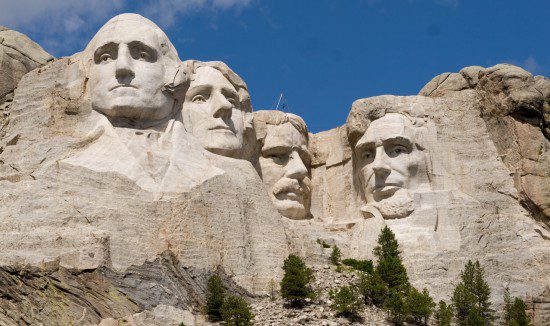

Jumping off of Washington’s nose on Mount Rushmore would be fatal. (This is how Martin Landau dies in North by Northwest.) But Bloom did not jump off anything when the band played the Mount Rushmore festival because the band never played the Mount Rushmore festival and also because no band has ever played the Mount Rushmore festival because it does not exist.

And yet this hitchhiker, and other fans over the years, told Bloom they remembered seeing him make that leap at a festival that never happened.

Obviously what those fans said wasn’t true. They could not have seen something that never happened and they could not remember attending a concert that never took place. But I don’t think they were lying, either — not exactly. I think what they were doing — and what Melzer and Pearlman were doing in creating and spreading such tall tales — was something more playful.

Melzer and Pearlman were concocting a rock-and-roll fantasy world and inviting fans to join in that fantasy, expanding and elaborating it in a collaborative effort. This isn’t what we usually think of as “lying” — as deliberately stating falsehoods in an attempt to deceive others. It’s more like improv, with its insistence on always saying “Yes, and …”

So this reminds me of Doveland, Wisconsin, “The Town That Wasn’t There.”

What makes Doveland so fascinating is that there are no records of a town with such a name, the town was not renamed or altered its zoning, and there is no map of the state that includes the coordinates of a town called Doveland, Wisconsin. Yet people claim they remember the town, had friends or relatives who lived there, have visited it, and a few folks have souvenirs to prove they have been to Doveland.

How could an entire town and its residents suddenly disappear into the ether?

Lauren Dillon writes about the various ways some American towns have been erased — like those flooded beneath reservoirs formed by dams. And the ways that some towns were abandoned — like dried up mining ghost towns, or the temporary towns constructed around former military bases. Doveland isn’t like any of those.

What it is, rather, is a game. Dillon’s article says “hoax,” and that’s accurate too. But it’s not only, or even mainly, the kind of hoax that aims to deceive others. It’s a mutually constructed hoax cooperatively created as a kind of play. Because it’s fun.

The internet is full of such games and it has made them larger and easier to share than they ever were with the slower forms of mass media available to guys like Melzer and Pearlman back in the ’70s.

I should have seen that coming, but I didn’t. Back in the late ’90s and early 2000s, it seemed like the Internet (we capitalized the word back then) was going to put an end to the naive acceptance of urban legends. Pioneering sites like Snopes collected and debunked various tall tales, documenting the receipts. If you heard an implausible tall tale, all you had to do was dial up and run a quick AltaVista search, and you could soon find a well-researched, footnoted-and-hyperlinked post tracing the origins of the legend, the history of its various permutations, and the actual facts of the matter.

Urban legends sites were popular because the legends themselves were popular because they were, for the most part, well-told stories. Discussing them was fun. The business of debunking such legends involved taking them apart to see how they were made, how they grew over time, and how they worked. And thus, as internet users learned to identify and debunk such legends we also learned, at the same time, how to create them.

Some of these new legends were created deliberately in forums where people who enjoy this kind of game gather to play it together. Some of their efforts fizzle, but others seem to take on a life of their own, spreading and mutating beyond the small group of original players. That’s how “Slenderman” came to be, and also, apparently, “Doveland.”

This form of play often seems absurd to those outside the in-group or subculture of players. Those outsiders do not accept the invitation to play this game. They usually don’t even recognize that invitation for what it is. To them it just seems like a lie.

“I saw the lead singer of Blue Öyster Cult jump off Washington’s nose during a concert at Mount Rushmore.”

“No. No you didn’t. Here is a picture of Mount Rushmore. Set aside the impossibility of staging a concert there, just look at Washington’s nose. Here is a picture showing, very clearly, how Washington’s nose is hundreds of feet above a sheer cliff. Jumping from there would be suicide. You have proven yourself to be either a liar or else a very, very silly person who cannot tell the difference between fantasy and reality.”

The outsider isn’t wrong there about the story. That story is absurd and obviously not true.

But their harsh assessment of the game-player isn’t quite accurate. The falsehood the game-player is spreading isn’t intended to deceive and it isn’t a delusion. Most people participating in such games can still tell the difference between fantasy and reality — they just like the fantasy better. They prefer it.

That’s understandable. Fantasies should be cooler, more exciting, and more appealing than mere reality, otherwise why bother fantasizing about them? The fantasy is fun. That’s why you play the game.

Alas, though, for some people the appeal of this fantasy is so much greater than the depressing facts of their day-to-day reality that they can’t bring themselves to stop playing the game. Ever.

Photos and other evidence won’t snap them out of it because their choice wasn’t due to a lack of evidence. That choice was the result of the relative misery of their reality versus the exciting appeal of the fantasy. It’s still not quite a delusion — an inability to know the difference between reality and fantasy — because it’s always still a choice and that choice is only available to those who can and do know that difference.

So this can all be complicated, nuanced, and layered. Just because someone is telling you an impossible story doesn’t mean they’re either an evil liar or a foolish dupe. It may be some tragic, heart-breaking combination of the two.

Most likely, though, the story-teller is just playing a game.

“Abortion anecdote from DeSantis at GOP debate is more complex than he made it sound,” three reporters write for the Associated Press, in a well-researched, painstakingly reported “fact-check” that utterly misses what’s really going on here.

Of course the story isn’t true. Of course the impossibilities it includes are impossible and of course no evidence can be found to support its ludicrously implausible assertions.

Because it’s a game. Ron and Penny are just playing a game and they’re inviting everyone to play along.

It’s undeniably a disastrous game that hurts countless real people, slanders all women, creates excuses for injustice, and bears toxic fruit for American politics and religion. But they think it’s fun and useful and better than reality. And they’re determined to keep playing.