Sociologist Joel Best is the Poisoned Halloween Candy Guy.

Best earned that title due to years of painstaking, published research into the baseless but enduring urban legend and moral panic. He literally wrote the book on the subject. If you want to talk to an expert who knows all the facts of the matter and who has thought deeply about what they mean, then you need to talk to him.

On some level, I suspect, Best is also a bit weary of having to be the Poisoned Halloween Candy Guy* — particularly this time of year, every year, when he winds up doing tons of interviews with journalists writing October stories reassuring parents that they don’t actually need to worry about Poisoned Halloween Candy because it’s never actually been a thing that has ever happened. Best teaches at UD, so the Delaware newspaper I used to work for had a local angle for that annual article and some reporter would call him every year as soon as the leaves started to turn.

Jennifer Byrne’s debunking of this perennial urban legend — “Why Halloween’s ‘Poison Candy’ Myth Endures” — also includes a mini-profile of Dr. Best and of what it means to be the Poisoned Halloween Candy Guy:

As the author of the 1990 book Threatened Children and the co-author of a study tracking all reports of contaminated Halloween candy since 1958, the University of Delaware sociology professor is arguably the nation’s foremost expert in “Halloween sadism.”

Halloween sadism is defined as the act of passing out poisoned treats to children during trick-or-treating. But even before the term was coined in 1974, parents already feared a mysterious, mentally unhinged candy killer for decades, despite a lack of supporting evidence.

For Best, who has updated his report every year since the 1980s, the month of September kicks off a sort of “interview season,” during which he inevitably fields calls from the press about the latest crop of claims.

“There’s always high anxiety in the years when something happens in September,” says Best. “Reports of poisoned candy increased after September 11. Whenever something unsettling happens shortly before Halloween, I get more calls that year.”

But this annual panic doesn’t require anything unsettling to set it off. Last year’s version, you may recall, involved a Fox News-fueled hysteria over some imagined “rainbow fentanyl” being passed out as candy to unsuspecting children.

“As you might imagine,” Best says, “the total number of cases of fentanyl in Halloween candy in 2022 in the United States was zero.”

The absolute, undeniable baselessness for that 2022 panic offers a lesson that America seems incapable of learning. That means poor Dr. Best is doomed to continue being the Poisoned Halloween Candy Guy until he retires and passes that title along to some younger apprentice.

What explains that? Best suggests it’s an expression about our anxiety over the safety of children:

Best says the fear of poisoned or otherwise tainted Halloween candy has come to serve as a proxy for very legitimate societal anxieties. In a modern world rife with looming threats … it is useful to be able to funnel these fears into a less unwieldy receptacle. By offloading anxieties onto a manageable yearly event, people can fend off a feeling of helplessness, says Best.

“If you think about it, Halloween sadism is the best thing in the world to worry about,” he says. “There is somebody in your neighborhood who is so crazy, they will poison little children at random. And yet, they’re so tightly wrapped, they’ll only do it one night of the year,” he says. “So on November 1, you wake up, look around the breakfast table and count noses. If everyone’s still there, you can say, ‘OK, we don’t have to worry about this for another 364 days.’”

But Byrne also talks to Elizabeth Tucker, a folklorist at Binghamton University, who notes that the Poisoned Halloween Candy legend echoes many of the themes of conspiracy theories about nefarious others threatening our innocent children — going all the way back to the ancient, antisemitic blood libel that still serves as the ancestor and template of every toxic conspiracy theory today.

That suggests something far less innocent. The blood libel and all of its Satanic baby-killer variations are not borne of a legitimate, innocent concern for the safety of our children, but from pride, self-righteousness, and the need to pretend we are Good by accusing some marginal Other of being superlatively evil.

That suggests something far less innocent. The blood libel and all of its Satanic baby-killer variations are not borne of a legitimate, innocent concern for the safety of our children, but from pride, self-righteousness, and the need to pretend we are Good by accusing some marginal Other of being superlatively evil.

There’s more than a hint of that in the Poisoned Halloween Candy legend.

I think there’s a distinction here between urban legends and conspiracy theories. The former, I would say, are distinct in that they do not require the existence of some nefarious, secretive, all-powerful cabal. The hook-handed serial killer terrorizing teenagers on Lover’s Lane is not part of some vast conspiracy. The story doesn’t involve or require any monstrously evil “They” or “Them” for it to be accepted as true.

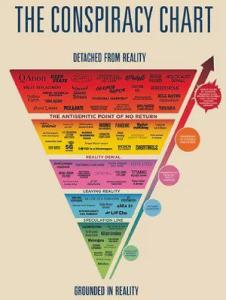

This relates to what Abbie Richards suggests with her insightful Conspiracy Chart and her notion of the trajectory of conspiracy theories ultimately requiring some such cabal or Them which, in turn (at least within Western Christendom) always wind up being identified as “the Jews.” Hence what Richards refers to as “The Antisemitic Point of No Return.”

I was reminded of Richards’ insight when reading this interview with historian Colin Dickey, author of Under the Eye of Power, which explores the history of conspiracy theories.

Dickey discusses the conspiracy theories about Freemasons that became massively influential in America during the 1800s. That led to the formation of one of the most important third parties in the history of American politics — the Anti-Masonic Party.** As Dickey says, “Freemasonry went from being a positive social philanthropic fraternal organization that people like Ben Franklin and Washington were proud to be associated with to increasingly being seen as this parallel shadow government that had infiltrated the country.”

I suspect part of the reason the Anti-Masonic conspiracy theory prospered when and where it did because those communities were otherwise lacking in Jews and Jesuits.

Jesuits always seem to be Plan B when conspiracy theorists embrace antisemitic tropes in a society that doesn’t have enough prominent Jews to make them seem to be a plausible candidate for a nefarious, all-powerful cabal. So in the absence of Jews, conspiracy theorists will go after the Jesuits as a proxy for them. (Liza Clark Diller has a fascinating discussion of anti-Jesuit conspiracy theories at the Anxious Bench — including a kind of anti-Jesuit Protocols still circulating online today.) In the relative absence of both Jews and Jesuits in many places in 19th-century America, conspiracy theorists had to fall back on Freemasons as Plan C.

Part of Dickey’s explanation for the appeal of conspiracy theories is similar to Best’s argument about the anxiety underlying the persistence of that Halloween legend. Dickey argues that conspiracy theories function as a kind of makeshift theodicy:

The conspiracy theory of society happens when you get rid of God and ask what’s in his place. What I found in writing the book and thinking through my other research in conspiracy theories is what they do is offer an explanatory mechanism for chaos and disorder and randomness, almost to the point of a quasi-theological explanation.

Anything that is happening today can be, if you so choose, understood to be part of the incredibly byzantine and hidden plan of the Illuminati that may seem confusing to us on the surface but you can trust as an article of faith that is part of their grand plan. They are both omniscient and omnipotent (unlike God they’re not benevolent) but they are working behind the scenes and that explains the world.

Even though that’s a malicious and terrible view of the world, for a segment of the population that is more reassuring than a world of pure chaos and disorder. People will cling to this idea that, yes, well, at least we know that this is part of this malevolent world order, even if it’s evil and out to get us.

I’m not sure it’s helpful to think of this as what “happens when you get rid of God.” Theodicy isn’t about God’s existence or non-existence, but about God’s apparent silence and seeming indifference to suffering and injustice. Theodicy is an attempt to vindicate God or to exonerate God of the charge of responsibility for the “chaos and disorder and randomness” of our apparently unjust world.

That’s what “theodicy”*** claims to be about, anyway. Usually, though, I think it’s a form of distraction by abstraction. It has less to do with God’s responsibility for the existence of evil than with our own anxiety about living in an apparently unjust, unpredictable, and unsafe world.

The classic text for theodicy is the Book of Job, and the characters in that story correspond to what both Dickey and Best suggest about the human anxiety driving belief in the “quasi-theological explanations” of conspiracy theories and urban legends.

In the first act of Job, his friends Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar argue that Job’s suffering must surely be the consequence of something he did wrong. Job’s sudden, random, massive misfortune has unsettled them and they’re desperate to have some tidy explanation that might reassure them that the same thing won’t suddenly happen to them. If Job did some secret Bad Thing for which he is being punished, then they could avoid that punishment by avoiding that Bad Thing.

Bildad et. al. know the world is a dangerous place and they hope for some secret trick that would enable them to navigate its dangers safely. This is, as Dr. Best suggests, one appeal of urban legends, which tend to offer a moralistic, reward-and-punishment explanation of the world like that sought by Job’s friends.

Bad things sometimes happen to children, but if you are vigilant and obedient, then bad things won’t happen to your children. Check your candy and you will be safe.

Conspiracy theorists, according to Dickey, are more like Elihu, the young theobro who shows up in the next act of the book of Job. Elihu, a kind of proto-Calvinist, argues that Job’s suffering is what everyone deserves. Job’s suffering, for Elihu, is simply “part of this malevolent world order, even if it’s evil and out to get us.”

Elihu wouldn’t say “malevolent” and “evil.” He would say, rather, that Job’s suffering was “part of God’s holy world order, which is so holy that it’s out to get us.” But it’s not clear to me how this understanding of “holiness” is distinct from malevolence and evil.

(The book of Job, by the way, weighs in on both of those arguments by having God appear in the final act as an on-stage character who tells them all to shut up because they’re wrong about everything.)

Most conspiracy theorists, I think, don’t believe that God is monstrously “holy.” Nor are they atheists who have “gotten rid of God” and replaced God with a godlike but malevolent cabal of conspirators. I think they are people who continue to believe in a powerful and benevolent God, but who embrace a kind of dualistic theology in which the cabal functions as a kind of second, rival God.

This is similar to the dualistic theology of many “spiritual warfare” Christians, who believe in a “literal” Satan (based on a literal reading of every extra-biblical mention of this character they can find). This Satan figure functions as a rival God — a divine being who is omnipresent, omniscient, and omnipotent. (Or, maybe, just a teensy smidgen less omnipotent than the Good Guy God.)

The dualistic theology of God vs. Satan Christians implies some ultimate future resolution to this battle. I think that’s also true for the dualistic theology of conspiracy theorists.

So the next question is what kind of eschatology they propose for this final war between the dueling Gods. If they’re imagining some kind of otherworldly, premillennial apocalypse then we should expect their conspiracy beliefs to produce a kind of fatalism and withdrawal from cultural and political struggles. No sense trying to fight against the cabal here in this life, but just wait until the afterlife, when they’ll get punished and we’ll get rewarded.

But if they’re imagining a postmillennial apocalypse here in this world, well, that’s another story.

* Back before social media and search engine companies set out to sideline blogs, I occasionally met people who would say, “Oh, wait, you’re the Left Behind Guy!” I’d always pause for a beat before conceding that, “Yeah. Yeah, that’s me. I’m … the Left Behind Guy.” I was always grateful for the acknowledgement of the work I’d done to earn that designation, but part of me was also usually rethinking all of the life choices that had led up to my being able to claim that particular unpleasant niche as my own.

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I

Took the one that made me the Left Behind Guy

And that has made all the difference.

I suspect that Dr. Best feels something like this same mix of emotions whenever his phone rings in October.

** Jonathan Blanchard was an important abolitionist who later became the founding president of Wheaton College in Illinois. He was also a rabid anti-Mason and a leader of the Anti-Masonic Party. Wheaton has a fun online exhibit exploring Blanchard’s obsession with the subject that includes this anecdote:

Jonathan’s eloquence on secret societies was prolific. Charles Albert once asked at the dinner table, “Father, can we not speak about something in this house besides Free Masonry? I am extremely weary of the whole subject.”

*** Theodicy is a mug’s game. The only way to win is not to play.

“Why do the wicked prosper?” and “Why do the innocent suffer?” are legitimate questions. We can and should demand an answer to those questions from any and every entity that makes any claim of sovereignty.

But the whole “omnipotent vs. good” construct is more like an antinomy than an argument. It conflates “omnipotent” with “omniresponsible,” smuggling in a host of assumptions about power as the sole cause of every effect. It also assumes that if there exists a Greatest Power then that greatest power must also be the sole locus of power — that all might rests with the Almighty and nothing else, anywhere, possesses or exerts any might that might have any consequences. Feh.