The Jesuits just won’t go away. In my classroom today, when discussing Christian missions in China during the 17th century, students started asking about Jesuits and how or why they might be responsible for terrible events from the Inquisition through the US Civil War and then atrocities in Argentina. While I’m never surprised at conspiracies involving Jesuits, this was the most exhaustive conversation I’ve experienced in a long time. I was both bemused and impressed when a student pulled up “The Jesuits Oath” on his laptop, citing the Australian library as a source.

As someone who studies the Atlantic world in the 17th century, I understand how exciting concerns about Jesuits can be for Protestants, and particularly English-speaking Protestants. An order that was explicitly formed to respond to the Protestant Reformation, consisting of men who were not required to stay in communities, but who traveled widely and attempted to blend into the societies they emigrated to, could be extremely alarming. While Catholic plots were a regular concern for Protestant states, Jesuits especially captured the imagination of worried Protestants.

In fact, Jesuits were trying to convert Protestants and non-Christians in general to Roman Catholic Christianity. They did operate outside the law in England (where I’m most familiar with them) and like other Catholic clergy, they hid themselves and engaged in smuggling religious paraphernalia such as books and rosaries. There was a genuine attempt to change the religious calculus of the world toward loyalty to the Roman church. And in the 150 years after the Reformation, the wars of religion featured folks on all sides engaging in assassinations, espionage, and plotting of various kinds against states they wanted to gain control of. Protestants, fewer in number, and controlling weaker states, were on the defensive.

In the 16th and 17th century, the English monarchs regularly married Catholic spouses, who were often allowed to bring their priests and a few co-religionists with them to the palace. This caused worries about Roman clergy within the very corridors of power and the regular jockeying for power with the court now included threats of Catholic influence on the heirs to the throne. Catholicism was outlawed, but somewhere between 2 and 5% of British subjects appear to have remained committed to the older faith. Elite Catholic families, often aristocratic, practiced dissimulation in order to retain their lands and position. This resulted in a cloud of distrust around anyone who was suspected of Catholicism. Jesuits, as among the most active of the missionary orders, willing to take risks in places where their faith didn’t dominate, were known to be propping up this minority—and it wasn’t a stretch to see them serving as a fifth column ready to topple the government at any time.

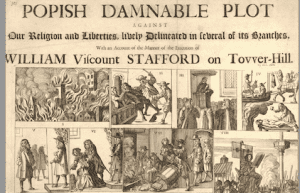

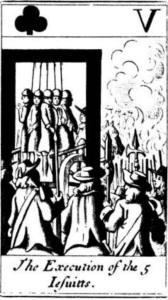

The ground was fertile for conspiracy. In the 1670s, the “Popish Plot” serves as the iconic model for what could happen when economic and political fears crossed with language about religious threats. Conflicts over the power of the monarch and foreign policy created space for Titus Oates, a social outsider who had flirted with Catholicism, to make money by testifying before Parliament outlining increasingly unhinged conspiracies about Jesuits plotting to assassinate the king. The nation went wild: newspapers reported a Jesuit army of 200, 000 invading from the north, neighbors reported on each other, and over 200 people were hanged, drawn, and quartered for the crimes of giving and receiving communion in the Catholic fashion. The assumption was that if you were Catholic, you were under the thumb of the Jesuits and plotting against the government.

There was no such conspiracy. Violence against Catholics would continue for another 150 years from time to time, though after 1681 there wouldn’t be any state executions of this religious minority. Jesuits themselves, often opposing Catholic elites in South America and France, were exiled and extirpated. (The modern version of Jesuits

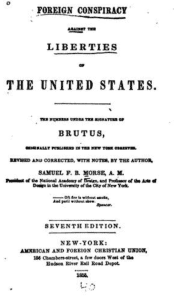

English-language political culture developed in the 18th century with the assumption that Catholics could not be truly in favor of rationality, liberty, or rights. In the 19th century, Pope Pius IX’s reign over the church further convinced Protestants that Catholics were against modernity, science, liberalism, and religious pluralism. The United States, faced with many immigrants from Catholic countries, became a hotbed of anti-Catholicism (often coinciding with general xenophobia) and conspiracies about oppressive and highly sexualized clergy. Titillating stories about convents with nuns servicing priests, resulting in babies that were killed after birth were very popular, along with legends about secret dungeons where Protestants were tortured (conflating the Spanish Inquisition with Catholicism in general).

It was one of these spates of anti-Catholicism that resulted in the so-called “Jesuit Oath” that my students found in the Library of Congress and the Australian National Library. And thus, an opportunity was formed for how historians read, especially how we approach primary sources. We ask–who wrote the document? When was it written? What was the context? What kind of document is it and where was it produced? It doesn’t take long in asking these questions of the “Jesuit Oath” to learn that it bears no relationship to actual Jesuits but was produced as part of anti-Catholic polemic in the 19th century. We can then be interested in the document, not as proof that Jesuits all actually swear to tear heretics apart limb from limb, but as a demonstration of what English-speaking Protestants in the US were worried about. In this way it is similar to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which would be really alarming if it represented something that actually occurred, but is instead a creation of anti-Jewish writers in the past.

Conspiracies are notoriously difficult to prove wrong. But we can start with the fact that just because something was written in the past doesn’t make it accurate. Historians don’t simply say “oh that’s a lie”—we look at the context of a document to find out what purpose it was serving and what ideas and practices it represents. The Jesuit Oath reveals a great deal about the United States in the 19th century. It tells us about what worries Protestants had, about the values of some people in the society that produced it, it can take us into research about political campaigns and the history of immigration, and the limits of religious pluralism. Debunking conspiracies doesn’t mean serving as cheerleaders for Jesuits—or for Christians of any kind. Humans have behaved badly, including Jesuits. People have actually tortured each other and attempted to overthrow governments or spied for foreign powers. We can tell the truth about the past without (to use Rodney Stark’s phrase) “bearing false witness.”

There may not be secret Jesuits everywhere, but in my classroom even the fictional ones can teach us about how to evaluate evidence, and to ask questions before we pass along exciting and incendiary YouTube videos, social media posts, or other elements that pass for “information.” While there’s a thrill that comes with thinking about secret knowledge, it can be equally satisfying to recognize when we are thinking clearly and observing fallacies. And then we can spend some energy on problems that are actually solvable.