Recently the Conference on Faith and History hosted a panel on witch hunts, both in history and in the contemporary world. We found ourselves asking the question—why is there a perennial interest in witchcraft history and the study of persecution of witches for both our students and the reading/watching public? Why is this so attractive to us? What seems clear is that we like stories with clear villains and victims and the inquisition and witch hunts seem like they provide us with this. There is secrecy and titillating violence and torture, and as many sociologists have argued: humans like their monsters. Perhaps we don’t want to be part of witch hunts. Rather, we want to read about and study them, so we can feel good that those other monsters (persecutors) are well and truly put to bed.

While humans have always had their monsters, with the attendant myths that explain them, historical witch hunts, in the popular imagination, are often rooted in the early modern Atlantic/European world. Phillip Jenkins reminds his readers that witches and witch hunts have been and still are common in many places around the world, but this essay focuses on ones the “Western” world engages most. Scholars agree that climate change in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries combined with large scale religious wars, the integration of the Western Hemisphere with its new people and ecologies, and the widening literacy and focus on legal rationalism all contributed to a concern with Satan, witches, heresy, and the role of the supernatural in local communities. Both Protestant and Catholic societies had their witch-hunts and inquisitions, in all their variations, over the 200 years leading up to the Enlightenment era.

The compulsion to find a way to explain the fears and challenges that we can’t control is fundamental to humans. We are meaning makers. We want a narrative that makes sense to us. In the decades after the integration of the Americas and the Protestant Reformation, Christians in Europe started forming new identities around their national languages, new political states/empires, and religious commitments. The expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain was part of this.

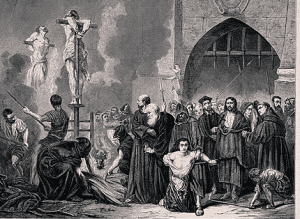

The Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella set up the Inquisition to root out any secret Jews or Muslims, who might be undermining their desired unity of the Roman Catholic faith. Within Spain, those victims of the Inquisition were primarily other Spaniards who claimed to be Catholic, not secret Spanish Protestants. In fact, Catholic and Protestant communities rarely used witch hunts to attack other denominations. They usually went after those of their own tradition, who seemed to have access to power and influence and were using it to harm others. In the Americas, the Spanish Inquisition was more concerned with the nefarious use of witchcraft that they perceived as coming from indigenous Americans (those they called “Indians”). They didn’t see Indians as fully formed Christians who could be held accountable by the Inquisition, but many Spaniards and mixed-ancestry folk, who were pulled into the Inquisition, had connections with Indians and their access to supernatural power.

While witch hunts varied from place to place, they were attempts to connect the continued belief in the supernatural powers and transcendent power of the Christian worldview with the newly developing commitment to literate and legal rationality. Specific forms of evidence and causation were desirable. The belief in a good and powerful God existed alongside a sense that some of the bad things happening were caused by people accessing evil power, or who believed the wrong things and were therefore causing displeasure to God or undermining the body politic. In England, the peak moment for witchcraft trials was during the Civil War/Interregnum period, when society was in chaos and folks really wanted to have some security that God was on His throne and the powers of Satan could be detected and curbed. In parts of Switzerland, the primary witchcraft concerns centered on evil actions against farm animals, the locus of most farmers’ wealth. When disaster, such as disease, accident or fire occurred, folk wanted to make sure they could prevent it or declare themselves innocent of wrong. In times of greater uncertainty, they looked for scapegoats.

While elites in the Atlantic world began to eschew witchcraft as an explanatory model after the Enlightenment, almost right away worries began about less supernatural groups. Conspiracies regarding the Illuminati and/or Freemasons flourished. Colin Dickey’s work has traced worries about elections in the early years of the United States to rumors and pamphlets asserting the role of secret societies. Protestant communities belief in nineteenth century Illuminati conspiracies or theories concerning secret Catholic underground activity were gradually replaced with alertness to Communist subversives in the twentieth century.

Scholars of the phenomenon of witch hunts connect the emotions behind them and their contexts to contemporary conspiracy theories. Who can be blamed for the anti-social behavior of the young? Maybe cults or satanism or “rock music” (in the 1970s and 80s). How might we handle the worries about latch-key children and the increase of women in the workforce? Perhaps we focus on kidnappings or child-trafficking (in the 1980s and 1990s). Even in a time when crime decreased and risky behavior declined among youth, the US in the 1990s and early 2000s was full of warnings about the dangers of video games, popular music, and Harry Potter books. In a world full of conflicting information, with no strong sense of central authority (for better and worse), humans want some sort of explanation for how decisions get made.

The hunt for nefarious actors, as a method of explaining uncertainty, is one explanation. But today we enjoy watching/studying those times when witch crafts have happened, and we often identify with the victims of the conspiracies. I think in many ways, my students’ obsession with learning about witch hunts, the Holocaust, and McCarthyism is connected to their desire to not be the monster. If we can explain why and how such persecution occurred, perhaps we can prevent it. The new monsters are those who have attempted to root out the heretics, witches, and so-called bad actors in the past.

Perhaps more fascinatingly, we may have transitioned from explaining real-world dangers to handling our fears through fiction, fantasy, and horror. On the podcast, “The Pulse”, Nina Nesseth and Arash Javanbakht recently shared research on our modern attempts to control our fears through film, roller coasters, and haunted houses. We all have fears and many of us find that seeking out a certain kind of scary experience can give us a sense of control over it—the reassurance that everything will turn out okay in the end, if we obey the rules.

As someone who is teaching young adults and participating in a church community with children, all of this new scholarship is reminding me that doing away with fear and worries about the world, altogether, is not possible. However, there are clearly more or less damaging ways of attempting to gain control over our lives and preventing disintegration in our communities. Above all, blaming groups of other people for being responsible for all the bad has almost never proven to be either a) accurate or b) helpful. While I might want assurance that I and my loved ones are safe from disease or economic downturns, history seems to indicate that reading a novel or trying a new sport, or even learning to do public speaking, if that scares me, might be more useful than attacking a political party or isolating myself from my neighbors.