Jonathan Edwards was the Greatest American Theologian of his time, we say. And that may even be true.*

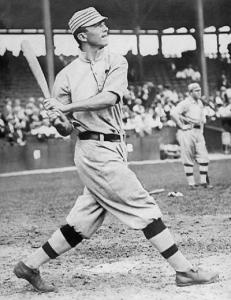

But it’s also true in the same way that Frank Baker was the Greatest American Slugger of his time. That’s why they called the man “Home Run” Baker, after all — hitting twelve home runs in a single season earned you a nickname like that in the dead-ball era.

Or think about the enduring influence of the Greatest American Composer of the 1700s. Who was that, you ask?

I’m asking too. Does anybody know? Or care? Or need to know or care?

I’m sure that music history people could provide us a list of candidates for that title and could probably get into heated arguments for and against various American composers who might have a claim to it.

And that’s all good. If some music historian wants to write a two-volume biography arguing that Francis Hopkinson deserves to be remembered as a composer just as much as he is remembered as a signer of the Declaration of Independence, then I hope they do so. The world will be richer for it.

And if some music aficionado writes a passionate blog post on “Why You Need to Stop Everything and Listen to Charles Theodore Pachelbel’s Magnificat” I’ll probably read that and give it a listen and broadly accept that this lovely composition deserves to be remembered and merits the writer’s enthusiasm.

But I probably still won’t read that two-volume biography of Francis Hopkinson: Composer, because for those of us outside of the niche world of Early American Classical Music Studies it’s not really an urgently necessary topic.

I’m not at all suggesting that non-specialists should dismiss these composers and their music. I’m sure Hopkinson’s works are worth a listen. And I’m glad choirs are still performing the Palmetto Pachelbel’s Magnificat. People over here in the backwater colonies were producing substantial works of great beauty and insight that can still reward our time and attention, even if they weren’t at the vanguard or the pinnacle of the craft compared to what was happening elsewhere.

But for all that, the fact remains that outside of the niche study of American musical history, none of the Greatest American Composers of the 18th century is enduringly influential.

If you were writing a sweeping history of the development of classical music from its origins to the present day, you could easily skip over even the most accomplished composers of Colonial America without losing anything essential from the story. You might want to include some mention of them in an effort to be comprehensive, but you wouldn’t need to spend a great deal of time discussing their influence on the development of the music because, well, they really didn’t have much.

We can’t quite say the same thing about the Greatest American Theologian of Colonial America, but the truth about the influential contributions of Jonathan Edwards to theology is probably closer to that end of the spectrum than it is to the attempts to portray him as an early American Augustine. If you’re writing a sweeping history of the development of Protestant theology from its origins to the present day, you’ll probably want to mention Edwards, but you won’t need to spend a whole chapter on his many unique contributions to our theological thought because, well, he didn’t actually have a whole lot of those.

There is, in other words, a kind of Washington Irving factor in all of this discussion of Jonathan Edwards. Every anthology of American Literature is going to include something from Washington Irving because they need to put something American in there to cover that period of time, which is otherwise mostly slim pickings. An anthology of world literature covering that time period probably won’t include anything from The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, but if the exercise requires some representative of American literature that includes something about which we Americans can say “That’s ours,” then Irving is gonna have to be included. (That same anthology of American lit will likely also include Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of An Angry God,”** because the literary output of the colonies pre-Irving was so sparse that poems, plays, stories, and essays have to be supplemented with sermons from that time.)

So if you’re writing the theological equivalent of that American lit anthology — some more narrowly focused history looking only at Reformed Protestantism or only at Protestant theology in America — then you might need a whole chapter on Edwards. In that narrower context, Edwards’ influence is more essentially significant. But it’s also a bit slippery. This has to do with the First Great Awakening.

This is another of the grand titles often assigned to Jonathan Edwards — the Great Theologian of the First Great Awakening. The impact of that “awakening” on American Christianity and American culture is undeniably important, and Edwards’ role in that awakening is likewise important. But the significance of his theology in that role is harder to describe.

The revivalism of the First Great Awakening was picked up on by visiting British evangelists like Wesley and Whitefield, but their role is far easier to explain. They were Methodists — or, at least, they were creating Methodism — meaning they were anti-Calvinists and people for whom revivalism and conversionism was a natural expression of their essential theology.

Edwards was a Calvinist. Revivalism does not seem to flow naturally from TULIP Calvinism. It’s not obvious that revivalism is even compatible with TULIP Calvinism.

Here in America, today, you can hear a Reformed preacher offer a ferocious sermon advocating the doctrine of predestination, affirming his staunch and unwavering commitment to unconditional election, limited atonement, and irresistible grace, and then you can hear him end that sermon with an altar call in which the congregation quietly sings “Just as I am, I come” and listeners are invited to choose to come forward to make a decision for Christ.

The staggering incoherence of that is difficult to explain, but it traces back to Jonathan Edwards and the revival that broke out in Northampton way back in 1733.

Edwards’ own revival sermons didn’t include that altar call. He mostly just laid out his Calvinist doctrine, explaining as starkly as possible that some few would be the undeserving recipients of God’s overwhelming grace and that everyone else was screwed — helplessly doomed to the damnation that all of us richly deserve. That didn’t leave room for an altar call. One wouldn’t expect it to leave much room for revival or “awakening” either. If you read those sermons, and accept the premise of them, then all you seem to be left with is the desperate hope that you might be among those with a winning lottery ticket. But just because you and Edwards might both hope and want that to be true for you, there was no guarantee it was, and there wasn’t really anything you could do about it anyway.

Having read some of Edwards’ other writings I think he’s a bit squishier than he wanted to admit on that point. One gets the sense, frequently, that he’s arguing something like “Human volition plays absolutely no role in salvation, but …” after which he describes something that sounds suspiciously like a role for human volition even as he insists it’s not that. One also gets the sense that Edwards sometimes leans — or at least hopes — toward a more expansive understanding of limited atonement. Yes, he tends to be very “wide the gate and broad the way that leadeth to destruction,” but he also seems open to the possibility that a substantial proportion of those in attendance at his sermons somehow beat the odds and are among those predestined for the narrow way that leads to salvation.***

I’m not really sure how Edwards squared the circle to produce his Reformed revivalism, but it exists. Conversionist Calvinism is a thing and it became a thing thanks, in large measure, to Jonathan Edwards. That’s evidence of his enduring influence.

But if the revivalism of the Great Awakening is the basis for our anointing of Edwards as the preeminent theologian of his time, the outcome of that revivalism might also undermine his case. A far greater number of Americans were church-goers after the Awakening than had been before. But most of those new converts and newly committed church-goers were Methodists and Baptists, not Reformed Congregationalists.

Still, though, that Awakening was pretty Great, and if Edwards was instrumental in starting it, then he probably deserves the whole “Greatest American Theologian of His Time” honorific. Just like Frank Baker deserves the name “Home Run.”

That’s not to disparage either one of them. Do you know how nearly impossible it was to hit one of those saggy, heavy balls over the fence? To do that 96 times earns you a spot in the Hall of Fame.

But Baker’s still not anybody’s pick as the starting third baseman for their all-time all-star team. Baseball Reference ranks him somewhere between Graig Nettles and Buddy Bell on the all-time list.

And if we’re going to insist on ranking theologians, that’s about where I’d rank TGATOHT too. Legit all-star. Very good player. Maybe even a borderline hall-of-famer.

* We seem to want it to be true. That’s understandable, because awarding this title to Jonathan Edwards spares us from having to concede it to anyone named Mather. That would be embarrassing. Though it’s still not clear to me why Salem in 1692 should be regarded as more shameful than New York City in 1741.

We also want the “Greatest American Theologian” of this time to be, you know, American. One of us and not just some visiting foreigner touring the colonies before returning home to England. So we’re in need of somebody local we can put up against Whitefield or Wesley.

Maybe the most interesting part of the “Jonathan Edwards was the Greatest American Theologian of his time” discussion involves the reasons for dismissing other contenders. Quakers need not apply because, I guess, Massachusetts outranks Pennsylvania or something. And anyway John Woolman and Benjamin Lay weren’t theologians. One was a saint and the other a prophet, and those don’t have anything to do with theology.

Oh, and no fair nominating anyone from outside the bounds of the 13 colonies. As Philip Jenkins points out, American history is always told right-to-left and east-to-west, and nothing counts in any of the places that became America until after they became part of America. Junipero Serra can’t possibly be compared to Edwards because Serra was a Spanish-speaking Catholic and Spanish-speaking Catholics don’t count as Americans — they’re just some of the unimportant people that Americans took America from.

** Many proponents of Edwards as The Greatest American Theologian of His Time don’t want to talk about “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” because they feel TGATOHT should not and cannot be reduced to a single famous sermon. That’s fair.

It’s also fair to note that Dexys Midnight Runners released six successful albums in a long career, including many singles over the years that appeared on the UK pop charts. Their greatest hits album — The Very Best of Dexys Midnight Runners — has 19 songs on it. And 18 of those songs are not “Come On Eileen.”

But it’s also kind of dumb to think you can ever talk about Dexys Midnight Runners without talking about “Come On Eileen,” a song that came out more than 40 years ago but still gets played at every wedding reception with more than 10 white people in attendance. No, it’s not the only thing they ever did, but it’s what they’re famous for, and it works as a representative and example of the rest of their work.

*** The word there isn’t “salvation,” of course, but “life.” And while this passage from the Sermon on the Mount is often cited as extolling limited atonement, it’s also entirely premised on human choice — “enter,” “find” — and teaches that membership in the kingdom of heaven is contingent on the fruit of good works.