Today, in 2024, when you see a person or a group described as “evangelical Protestant” that term is meant to distinguish them from mainline Protestants. “Evangelical” as opposed to “mainline.” That’s how this word is used and thus is at least part of what it means. The larger group of (western) Christians includes both Catholics and Protestants. And among Protestants there are two main kinds — “mainliners” and “evangelicals.” That’s the general sense.

But that hasn’t always been the general sense. And that was very much not what “evangelical” meant to those who first claimed the term. Those folks — Billy Graham, Carl F.H. Henry, Harold Ockenga, among others — began rebranding as “Neo-evangelicals” (they later dropped the “Neo-” bit) — in the hopes of carving out a third category between what were then regarded as the two main kinds of Protestants, “fundamentalists” and “modernists.”

Those terms go back to the “Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy,” an early 20th-century tussle among Presbyterians spread throughout other denominations and nondenominational congregations. The tensions and factions here were not brand new, but the split created a real division, separating American Protestants into two camps or categories that, in turn, clustered around or built new institutions. This is more or less when “mainline Protestants” became “mainline Protestants” — the pre-existing denominations that retained most of their prior institutional structure as the fundamentalists broke away and separated from the main lines of denominational Protestantism. Before this, nobody needed to talk about “mainline” Protestants — they were just, you know, Protestants.

The fundamentalist side of this split was then — as it is now — a diverse and sometimes messy collection defined as much by what they were against (“modernism”*) as what they were for (“the fundamentals”). In the first half and through the middle of the 20th century, mainline Protestantism was generally respected and respectable in a way that fundamentalism generally wasn’t (see, for example, the Scopes Monkey Trial, or the massive popularity of the 21st Amendment overturning Prohibition). Ecumenical mainline Protestantism influenced the broader culture and engaged with it in a way that many fundamentalists could not or would not. “Fundamentalist” was not a winning brand name.

Thus the hugely successful creation of a new brand — “Neo-evangelicalism” — in the 1940s and ’50s. This was a movement that broke away from the rest of fundamentalism the same way that fundamentalism had broken away from the rest of denominational Protestantism.

“Evangelical” was chosen as a new name to distinguish this new movement from the rest of fundamentalism. It was a name that meant, essentially, “We’re fundamentalists, but we’re not like those fundamentalists.” Billy Graham was the poster boy for this new brand of “Don’t call us ‘fundamentalists,’ we’re ‘evangelicals’ now.” He meant it. This was, after all, a guy who initially enrolled at Bob Jones University, couldn’t stand the place, and wound up transferring to Wheaton College where he found a strain of fundamentalist Christianity that didn’t make the term seem quite so pejorative.

This re-branding of Fundamentalists But Not Like That as “evangelicals” involved not just claiming this new use of an old word for themselves, but also projecting it backwards into the past, re-christening prior generations of Protestants that they liked as “evangelicals” and representatives of “evangelicalism.” That anachronistic** usage was widely accepted, and boosted the success of the re-branding effort, strengthening its asserted distinction between “evangelicalism” (the good and proper and respectable form of fundamentalism) and “fundamentalism” (the rest of the fundamentalists who weren’t on-board with the re-branding).

Joey Cochrane touched on some of this history earlier this year at the Anxious Bench, writing:

The emergence of mid-twentieth century evangelicalism, often referred to as “New Evangelicalism” or “Neo-Evangelicalism,” created an influential conglomerate for the purpose of regaining cultural and political power, and it was nothing short of a re-branding effort of conservative, reformed, protestant Christians, who had witnessed how the “Fundamentalist” brand power had been diminished in the public’s eye by modernist pastors like Harry Emerson Fosdick and journalists like H. L. Mencken. I have come to refer to this turning point in the history of Protestant Christianity in the States as the birth of the Brand Evangelicals.

Cochrane’s description is somewhat playfully cynical, but none of this is controversial or obscure. The re-branding — the invention of “evangelical” Christianity — isn’t some wild theory pieced together from arcane documents unearthed in some archive. It was an explicit, public, media effort. It involved theological treatises but it also involved press releases and a media campaign conducted with the considerable might, charisma, and savvy of Billy Graham Inc.

What Cochrane describes there is A Thing That Happened, in public, and fairly recently.

And, again, my point here is that this re-branding — this claiming or re-claiming of the word “evangelical” — was not intended to differentiate between “evangelical Protestant” and “mainline Protestant.” It was intended to differentiate between “evangelical” and “fundamentalist.”

That’s what the term meant for most of the middle of the 20th century. It was still true in the 1980s, when I was a member of a fundamentalist church and a senior at a private, fundamentalist Christian school. I had applied to three colleges: Gordon, Messiah, and Eastern. This dismayed many of the good folks at both my church and school, who viewed such places as squishy, backslidden, and downright dangerous, because they were evangelical. One concerned church member told me I’d be better off going to Rutgers, because at least then I’d be prepared for the danger. Then they quoted the warning to the church in Laodicea from Revelation 3: “I would thou wert cold or hot. So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spew thee out of my mouth.”

That was how fundamentalists understood the word “evangelical” for a full generation after Graham & Co. coined the term. And it was how most evangelicals understood the word themselves. This is how the term was originally intended to be used — what it was meant to mean. It meant you were the kind of Protestant who went to Wheaton instead of to Bob Jones. You were someone fully committed to the fundamentals, but Not That Kind of Fundamentalist.

If the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy was a schism among American Protestants, the “Neo-evangelical” rebranding was a schism among fundamentalists. We could call it the Fundamentalist-Evangelical Controversy. And the evangelical side of that schism was, initially, triumphant. The Neo-evangelicals built a series of successful, thriving institutions — Fuller Seminary, Christianity Today, the National Association of Evangelicals. And the new brand was so successful that it was adopted by scores of pre-existing institutions. Look again at those colleges I applied to. All of them pre-existed the mid-20th century rise of “Neo-evangelicalism,” but by the time I was visiting them in the 1980s, they were all self-describing as “evangelical.”

The triumph of the evangelical side and the success of the rebranding effort changed the context. In this new context, the word “evangelical” took on new meaning — the meaning that it has today. The original meaning of “evangelical as opposed to fundamentalist” increasingly gave way to the new meaning of “evangelical Protestant as opposed to mainline Protestant.” Instead of the kind of Protestant who went to Wheaton instead of Bob Jones, it meant the kind of Protestant who went to Wheaton instead of Oberlin.

Basically, the “third way” between fundamentalism and modernism that the Neo-evangelicals had sought to create was so successful that it was no longer the third way, but the second, and it became the dominant term for those American Protestants who were not mainline Protestants.

That led to a strange development that isn’t much discussed. Roger Olson mentions this once in a while — see for example this 2019 post from him, “The Fundamentalists Are At It Again” — but mostly it goes unremarked or unnoticed. Once “evangelical” came primarily to differentiate between evangelicals and mainline Protestants, it also began to refer to all Protestants who are not mainline Protestants, and thus came to include the very same fundamentalists it was originally intended to distinguish it from.

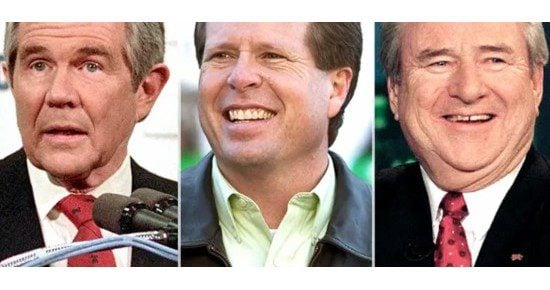

Today, even fundamentalists who are, emphatically, Exactly That Kind of Fundamentalist — the kind Billy Graham was so eager to distance himself from — will describe themselves as “evangelical.” There are still just as many fundamentalists as there were before the Scopes Trial, but nobody seems to use the term for themselves anymore (apart from a very few holdouts, like Bob Jones MCVII or whatever number they’re on), Fundies like Al Mohler or John MacArthur or Tony Perkins are routinely described by themselves and by others as “evangelical.” Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University is now an “evangelical” college. So is Moody Bible Institute. The wildest snake-handling fundie weirdos of the CharisMAGA fringe are all “evangelicals” now too.

The upshot of this is that today, most “fundamentalists” are “evangelicals.” And, because that subset is larger and louder, most “evangelicals” are “fundamentalists.”

Billy Graham took on the fundamentalists and it seemed like he won. But now Billy Graham is dead and the fundies have pulled off a comeback. The rebranding meant to isolate them has given them more power and influence than Billy ever dreamed of at his peak.

* Ironically, as folks like George Marsden and Mark Noll have pointed out for years, fundamentalism was itself an extremely “modernist” phenomenon. Both sides of the modernist/anti-modernist split adapted to and adopted “modernism” in their own way. Have I recommended Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind recently? If not, time to do so again.

** That’s a fightin’ word here. Want to start a fight among usually staid, moderate white evangelicals? Just pick some admirable Protestant from a previous century — I dunno, Adoniram Judson, say — and ask if they were “evangelical.”