The emergence of mid-twentieth century evangelicalism, often referred to as “New Evangelicalism” or “Neo-Evangelicalism,” created an influential conglomerate for the purpose of regaining cultural and political power, and it was nothing short of a re-branding effort of conservative, reformed, protestant Christians, who had witnessed how the “Fundamentalist” brand power had been diminished in the public’s eye by modernist pastors like Harry Emerson Fosdick and journalists like H. L. Mencken. I have come to refer to this turning point in the history of Protestant Christianity in the States as the birth of the Brand Evangelicals.

Devin Manzullo-Thomas is one among many historians of evangelical history, who has recognized this re-branding moment. In Exhibiting Evangelicalism he claimed:

Amid the boom in church attendance and religious affiliation after World War II, fundamentalist Christians and other conservative Protestants deployed evangelical heritage to forge what they termed “new evangelicalism,” a rebranding of the faith suited to postwar society.[1]

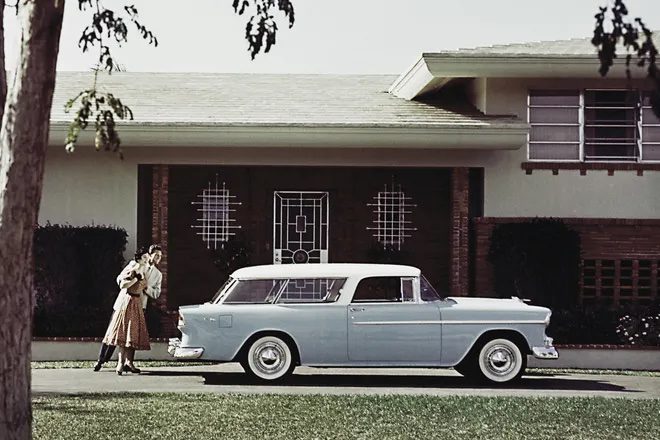

The timeliness of the rebrand to Brand Evangelical was somewhat fortuitous in that it occurred serendipitously with the emergence of a booming economy of mass consumption, characterized by the emergence of the suburbs, suburban shopping centers, station wagons and later minivans, and suburban stay-at-home housewives.

The suburbs provided families with spacious lots and homes to fill with new consumer goods. Station wagons and later minivans were roomy automobiles that allowed families to move those goods from the newly created suburban shopping centers to their suburban homes. Stay-at-home housewives were tasked with the responsibility to be the primary consumption decision-makers for the home, and their stay-at-home status provided the margin for them to run errands, visit the shopping center, purchase goods, and transport them home.

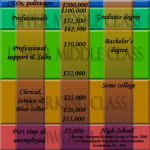

The momentum of the movement, which I like to call Brand Evangelicals, coincided nicely with the emergence of what historians have dubbed as the post-WWII Affluent Society, and this movement fostered a particular socio-cultural demographic. The makers of the Brand Evangelical movement were characteristically white, male, suburban husbands, and the affinity group most drawn to the movement was unsurprisingly much like the movement’s makers, white and suburban.

Brand Evangelicals as a conglomerate of broadly conservative, reformed, protestant Christians flourished for generations. However, the movement has fallen on trying times. The 2016 election cycle and Trump presidency led to strident criticisms of evangelicalism and its overwhelming support of the Forty-fifth President of the United States. As a result, some have described the evangelical movement as one that is splintering, fracturing, or fragmenting into factions. It shouldn’t be a surprise to us that the group that is most wrestling with how to navigate this tumultuous period for Brand Evangelicals are the same sort of socio-cultural demographic that had birthed and led the movement.

Kevin DeYoung offered four postures or responses to the issues of race, politics, and gender in his March 2021 TGC article entitled, “Why Reformed Evangelicalism Has Splintered: Four Approaches to Race, Politics, and Gender.” In pastoral fashion, the four approaches he offered were alliterated as 1) Contrite, 2) Compassionate, 3) Careful, and 4) Courageous. DeYoung argued that the factious issues of race, politics, and gender cultivated sensibilities that could not be reconciled. Rather than seeking a solution, he suggested settling for understanding the landscape while seeking a renewed focus.[2]

Similarly, Timothy Dalrymple began his April 2021 editorial for Christianity Today by teasing out the factious development in evangelicalism:

New fractures are forming within the American evangelical movement, fractures that do not run along the usual regional, denominational, ethnic, or political lines. Couples, families, friends, and congregations once united in their commitment to Christ are now dividing over seemingly irreconcilable views of the world. In fact, they are not merely dividing but becoming incomprehensible to one another.[3]

Michael Graham later quoted Dalrymple above in his follow-up analysis in June 2021 over at Mere Orthodoxy, where he re-iterated Dalrymple by arguing, “The reality is that while many in the evangelical movement thought their bonds were primarily (or exclusively) theological or missional, many of the bonds were actually political, cultural, and socioeconomic.”[4] Graham went on to offer a scheme for interpreting six ways that evangelicals are fragmenting from one another into the following subgroups: 1) Neo-Fundamentalist Evangelical, 2) Mainstream Evangelical, 3) Neo-Evangelical, 4) Post-Evangelical, 5) Dechurched (but with some Jesus), 6) Dechurched and Deconverted.

Following these articles, I listened to President Phil Ryken synthesize this literature at a Townhall Meeting at Wheaton College. Ryken endeavored to assess this literature, among other interpretations of the evangelical landscape, for the purpose of addressing how Wheaton College could attract the broadest group of evangelicals to study at the college while also fulfill the role of moderating and mediating between fragmenting groups of evangelicals.

It was in near proximity to this period that I had seen David Brooks’s February 2022 piece at the New York Times, “The Dissenters Trying to Save Evangelicalism from Itself.”[5] Brooks has been on his own spiritual journey, and as I understand it, locates himself within the Christian Faith.[6] He shares values and has some consonance with the main body of evangelicals, and even if merely evangelical adjacent, he has been a self-critical conservative, white, male friend to Brand Evangelicals for some time. Brooks’s dissenters piece narrates the experience of a hodge-podge of personalities who were prophetically speaking into the disorientation of the evangelical world. Brooks credits this disorientation of the evangelical world more to a series of scandals, while leaving room for the possibility that Trump ushered in a watershed moment that brought all this disillusionment to a head. Brooks was another one of the pundits Ryken had appealed to in his Townhall Meeting, though I don’t think it was this particular article that Ryken had referenced.

I recall leaving that Townhall Meeting with a mixture of responses that I cannot get into right now. Needless to say, one notion that struck me, after encountering all these interpretations of the evangelical landscape, was that the evangelical brand had taken some heavy blows and its historic champions (white, male, conservatives) were wrestling with how to reposition themselves and their movement next. It would undoubtedly be no small rallying effort for the brand to recover, if that were even plausible.

As time went on it became clear to me that some of the makers of Brand Evangelicals were clearly distancing themselves from the brand altogether, and some consumers had likewise disassociated from Brand Evangelicals. A more recent instance of one figure describing their own journey is Katelyn Beaty’s March 2024 Substack post, “What ‘Post-Evangelical’ Means to Me,” where she preferentially adopts Michael Graham’s notion of Post-Evangelical as more fitting than another common identifier, Exvangelical. Beaty distinguishes the two identities, saying:

I prefer post-evangelical to its angstier cousins, ex-evangelical or exvangelical, because it’s simply meant to describe a new stage of faith identity that comes after a previous stage of faith identity. It’s meant to describe a sequence rather than a reaction against.[7]

Both Exvangelical and Post-Evangelical have meaningful purposes for those individuals who are on a discovery process to determine what variety of Christianity they wish to consume next, since their taste and preference for the evangelical brand has altered. Incidentally, NPR journalist, Sarah McCammon, has published a recent New York Times bestseller, The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church, which is a helpful source for understanding the journeys of many, who have reacted against the evangelical brand, and sit anywhere on a spectrum of non-Christian to spiritual but not religious to merely non-evangelical.[8]

As a result of the deterioration of the evangelical brand, there are those who have called for the end of evangelicalism, and their efforts may even allude to the attempts of another re-brand for conservative, reformed, protestant Christianity. One such example of this new direction for Brand Evangelicals comes from Jake Meador at Mere Orthodoxy, who declared that the evangelical movement is dead. In his June 2023 piece, “The End of Evangelicalism and the Possibility of Reformed Catholicism,” Meador proclaimed “Evangelicalism is dead. It’s time to let the dead bury the dead.”[9] He then went on to promote the case for “Reformed Catholicism,” which I believe finds its roots in the scholarship of Scott Swain and Michael Allen, at Reformed Theological Seminary. These two Reformed Protestant theologians, who would likely locate themselves in a theological heritage that includes the school for the Theological Interpretation of Scripture as well as one that finds its heritage in the theologian John Webster, have constructed the theological foundation and communal language necessary for a rebrand, and their notion of “Reformed Catholicism” fits the bill for the sort of rebrand that keeps reformed protestant values at the center and appeals to the social imaginary of reformed protestant men like Jake Meador.

How Brand Evangelicals will rebrand is yet to be determined, but there is undoubtedly an attempt to keep Reformed Protestantism at the center of the brand. However, I believe this attitude perpetuates the short-comings of the Neo-Evangelicals and the Reformed Resurgence. Until evangelicals can set a truly broad ecumenical table, in the spirit of Lausanne, that reflects the texture and features of global Christianity, while also attending to a distribution of power among a diverse socio-cultural demographic, the movement, regardless of what name we attribute to it, will continue to suffer from the same dysfunction and dysphoria that has plagued it during the last four generations of Brand Evangelicals.

[1] Devin Manzullo-Thomas, Exhibiting Evangelicalism: Commemoration and Religion’s Presence of the Past (University of Massachusetts Press, 2022), 3.

[2] Kevin DeYoung, “Why Reformed Evangelicalism Has Splintered: Four Approaches to Race, Politics, and Gender,” The Gospel Coalition, March 9, 2021, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/kevin-deyoung/why-reformed-evangelicalism-has-splintered-four-approaches-to-race-politics-and-gender/.

[3] Timothy Dalrymple, “The Splintering of the Evangelical Soul,” Christianity Today, April 16, 2021, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2021/april-web-only/splintering-of-evangelical-soul.html

[4] Michael Graham, “The Six Way Fracturing of Evangelicalism,” Mere Orthodoxy, June 7, 2021, https://mereorthodoxy.com/six-way-fracturing-evangelicalism.

[5] David Brooks, “The Dissenters Trying to Save Evangelicalism from Itself,” New York Times, February 4, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/04/opinion/evangelicalism-division-renewal.html.

[6] Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “David Brooks’s Conversion Story,” The New Yorker, April 29, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/david-brooks-conversion-story; Russell Moore, “Losing Our Religion: David Brooks on the Allure of Tribalism,” Christianity Today, August 23, 2023, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/podcasts/russell-moore-show/losing-our-religion-david-brooks.html; “David Brooks on His Conversion,” Christianity Today, https://www.youtube.com/shorts/Lt4ck_fR8o0.

[7] Katelyn Beaty, “What ‘Post-Evangelical’ Means to Me,” The Beaty Beat, March 28, 2024, https://katelynbeaty.substack.com/p/what-it-means-to-be-post-evangelical-anxiety.

[8] Sarah McCammon, Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical Church (Macmillan, 2024).

[9] Jake Meador, “The End of Evangelicalism and the Possibility of Reformed Catholicism,” Mere Orthodoxy, June 12, 2023, https://mereorthodoxy.com/reformed-catholicity; Michael Allen and Scott Swain, Reformed Catholicity: The Promise of Retrieval for Theology and Biblical Interpretation (Baker, 2015).