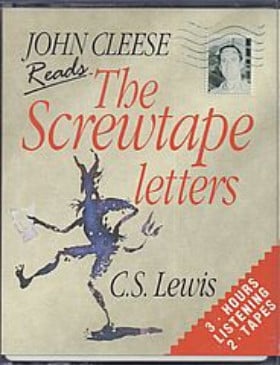

• A few folks in comments here the other day mentioned this excellent essay from Laura Robinson and I want to give it a bit more attention: “Three Questions to Ask Yourself Before You Try to Imitate The Screwtape Letters.”

This is a terrific exploration of why C.S. Lewis’ book works — partly because it’s a humorously self-deprecating work of introspection, and partly because Screwtape himself is such a memorable, comic character, a kind of David Brent of Hell. Robinson’s discussion of that helps us to better understand and appreciate Lewis’ classic, but even more so it exposes why his many, many, many would-be imitators fail so miserably.

This is a terrific exploration of why C.S. Lewis’ book works — partly because it’s a humorously self-deprecating work of introspection, and partly because Screwtape himself is such a memorable, comic character, a kind of David Brent of Hell. Robinson’s discussion of that helps us to better understand and appreciate Lewis’ classic, but even more so it exposes why his many, many, many would-be imitators fail so miserably.

One of the things I admire about The Screwtape Letters is that Lewis is confessional and relentless in the way he interrogates his own rationalizations, mixed motives, and internal struggles, but yet still manages to produce a book that, in the end, suggests that when he is just left alone to spend an afternoon sitting by himself enjoying a good book, it is a moment of cosmic significance that causes the princes of Hell to tremble.

(This is one thing Lewis’ American evangelical fans often miss in his work — that there is a recurring theme of his addressing them, directly, and telling them that, No, they may not deny him his books and his beer and his pipe.)

I’ve mentioned this before, but I highly recommend the audiobook of Screwtape as read by John Cleese. Perfect casting to capture the pompous, officious, inappropriate confidence of the character who is also, of course, an extremely British demon.

• Erik Loomis comes to Philly to visit the American grave of Octavius Catto. Considering the number of ballplayers he has covered in this series — he just did Minnie Miñoso — I thought we’d get a little more attention here to Catto’s history as a pioneer in the national pasttime (Walt Whitman almost certainly, at some point, watched Octavius Catto play baseball), but then I suppose his achievements as a champion of Reconstruction and desegregation really are more important.

Loomis shares this excerpt from an 1865 New York Times article on some of Catto’s activism:

Last evening a colored man got into a Pine-street passenger car, and refused all entreaties to leave the car, where his presence appeared to be not desired.

The conductor of the car, fearful of being fined for ejecting him, as was done by the Judges of one of our courts in a similar case, ran the car off the track, detached the horses, and left the colored man to occupy the car all by himself.

The colored man still firmly maintains his position in the car, having spent the whole of the night there.

The conductor looks upon the part he enacted in the affair as a splendid piece of strategy.

The matter creates quite a sensation in the neighborhood where the car is standing, and crowds of sympathizers flock around the colored man.

• And here is a Visit to an American Grave that is not from that series, and it’s the grave of someone who never actually lived: “Here Lies Charlotte Temple, the Woman Who Never Existed.”

Charlotte Temple, or sometimes Charlotte, A Tale of Truth, was a 1791 novel by Susanna Rowson. It’s a seduction novel — a tragic tale of a woman used and scorned and abandoned by cruel men. Probably not something you had to read in school, but it was a huge best-seller in its day — a big enough deal that somebody (nobody is sure who) decided to buy a grave plot and set up a marker for its heroine as a tribute, or maybe as a tourist-trap.

• Betteridge’s Law states that “Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no.” This applies to this piece by Yanan Rahim Navarez Melo for Sojourners: “Can Global Evangelicalism Save American Evangelicals From MAGA?”

Melo, who is from the Philippines, argues that we can’t understand “global evangelicalism” without examining the ways in which it is a product of American white evangelical colonialism. His argument is a good companion piece to Alex Mayfield’s recent post “Why Is It So Hard to Do Pentecostal History?” (a headline that shrewdly sidesteps Betteridge’s Law).

Glad to see both of those pieces as indicators that the conversation is moving beyond shallow invocations of “global” Christianity, especially when that language is used to defend white American Christianity as some pure, abstract form of religion wholly unaffected by cultural context.