Today is the birthday of Dorothy Day – the journalist and social activist who co-founded the Catholic Worker movement. To mark the occasion, I’m posting the essay I wrote about Day’s classic autobiography, The Long Loneliness. The essay first appeared in Besides the Bible: 100 Books that Have, Should, or Will Create Christian Culture (Biblica, 2010). I also encourage you to check out this wonderful video of Dorothy Day on the Christopher Closeup show.

Today is the birthday of Dorothy Day – the journalist and social activist who co-founded the Catholic Worker movement. To mark the occasion, I’m posting the essay I wrote about Day’s classic autobiography, The Long Loneliness. The essay first appeared in Besides the Bible: 100 Books that Have, Should, or Will Create Christian Culture (Biblica, 2010). I also encourage you to check out this wonderful video of Dorothy Day on the Christopher Closeup show.

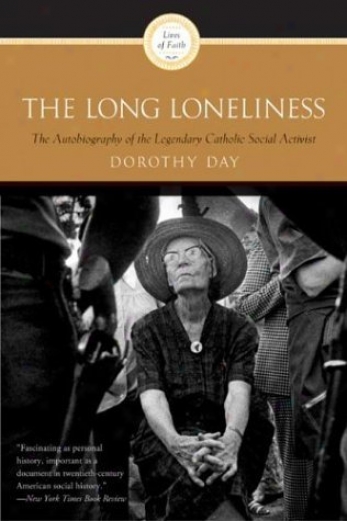

The photograph on the cover of HarperOne’s 1997 edition of The Long Loneliness, Dorothy Day’s classic spiritual autobiography, captures the cofounder of the Catholic Worker Movement at age 75, just minutes before she is arrested. Day had traveled to California’s San Joaquin Valley, grape country, to support the right of the United Farm Workers to strike. In the photograph, she is seated outside on a portable stool, legs crossed, hands on one knee, wearing glasses, a plaid dress, and a wide-brimmed straw hat. She is framed by two figures in the foreground. They are armed policemen, there to take her into custody, and Day looks up at one of them with an expression of serene defiance.

Great-grandmothers don’t often have FBI files 500 pages thick. But saints have a way of disturbing the peace. And by 1973, the year that photo was taken, Dorothy Day had been disturbing the peace for more than half a century—first as a radical bohemian, then as a radical Christian. Day converted to Catholicism in 1927 at the age of 30. Having spent the previous decade writing about issues of labor, poverty, and human rights for radical newspapers, Day lamented that the communists, socialists, and anarchists were consistently sacrificing their own well-being for the good of the poor and their fellow workers, while the church seemed unwilling to do the same.

Then, on a reporting trip to Washington, D.C., in 1933, the depths of the Great Depression, Day knelt in the national shrine at Catholic University and asked God to show her how to use her gifts to help the poor and disenfranchised. The very next day, she walked into her apartment back in New York and found a man waiting for her. His name was Peter Maurin and he was there to convince Day to start a truly permanent revolution—what Day would later describe as “a revolution of the heart, a revolution which has to start with each one of us ” The Catholic Worker was born.

The Catholic Worker opened houses of hospitality in inner cities, as well as in extremely poor rural areas. Day and Maurin also organized the Catholic Worker newspaper, which from 1933 to the present has been sold at a cover price of just one penny. Over the years, contributors have included Thomas Merton, Jacques Maritain, and Daniel Berrigan. Day served as the paper’s editor until her death in 1980. Maurin wanted to create a society in which it is easier for people to be good, and from the beginning, the Catholic Worker newspaper has staked out a position of extreme libertarianism, equally distrustful of the welfare state and big corporations because of their power to alienate a man from himself, his community, and God.

Catholic Workers also participated in bold acts of nonviolent disobedience against racism, social injustice, and war. Day was arrested multiple times in the late 1950s for refusing to comply with the rules of New York City’s civil defense drills. For her 1957 witness against the nuclear arms race, she was sentenced to thirty days in jail, where she worked on a book about her favorite saint, Thérèse of Lisieux, “the Little Flower.” Catholic Workers joined protests and picket lines. They held signs bearing quotes from papal encyclicals about workers’ rights. A policeman ordered to break up one such protest said it was like arresting the pope himself.

There are currently about 185 Catholic Worker houses of hospitality around the world, offering food, clothing, and shelter to those who are most in need. These communities provide active support of labor unions and human rights, and pacifism remains a central tenet of the movement.

Day once told a group of visiting Harvard students that the meaning of her life was to live up to the moral vision of the church, and of some of her favorite writers, including Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Dickens. Indeed, The Long Loneliness can be read as both the autobiography of a reader and a prooftext on the power of books to change lives.

The Catholic Church is currently considering Dorothy Day for sainthood, and while Day drew sustenance from the lives of the saints, one wonders how she would feel about the prospect of joining them. Day was asked about this once when she was alive, and she replied, in essence, “I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” Day seemed uncomfortable with the church resting on its laurels on her account. Not when there is still work to be done.