Then the LORD God formed adam as dust from the ground,

and breathed into his face the breath of life;

then adam became a living being. (Genesis 2:7)

In the opening scene of the Bible, death enters only thinly disguised in the specter of “dust from the ground.” This repetition—dust and ground in tandem—is an adumbration of human mortality, set as the curtain rises, to alert us to the inevitability of death, so that the first breaths of man and woman which follow should not bewitch us into the belief that life will last forever.

In the opening scene of the Bible, death enters only thinly disguised in the specter of “dust from the ground.” This repetition—dust and ground in tandem—is an adumbration of human mortality, set as the curtain rises, to alert us to the inevitability of death, so that the first breaths of man and woman which follow should not bewitch us into the belief that life will last forever.

The first human doesn’t just come from dust; the first human is dust from the ground. Dust is, in brief, our substance, not merely our source. Not even the animals are depicted with such disheartening hues. God creates them, as God created adam from the ground, but they are not depicted as dust: “So out of the ground the LORD God formed every animal …” (Genesis 2:19). Ground? Yes. Dust? No.

Then, just a few narrative moments later, rings another jarring note: God decrees death to adam: “In the sweat of your face you shall eat bread until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:19). Even in death, adam’s substance is dust and his source, the ground. Dust and ground–both.

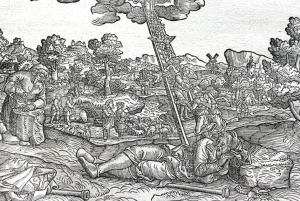

Smack in the middle of all this talk of dust and ground, we glimpse God’s bending and breathing into the first human’s nostrils–face, really–the breath of life. As a result, the human being becomes more than dust from the ground; the human being becomes a living being, a person with a capacity to till the garden, to chat with God, to name the animals, to pulse with sexual desire. The intimacy with which God imparts life, the face-to-face bestowal of breath, the dramatic transformation of lifeless dust from the ground into the first of our race—all of these together convey an emphatic affirmation of life, the quintessence of creation, and the core of human vitality.

When my daughter Chloe was a couple of years old, she’d climb onto my lap, stand unsteadily, set her small mouth full on over my nose, breathe deep—and blow. A full-force gale of toddler’s breath. Whoosh. I’d feel my nose fill, my head swell, and her breath sneak out of my eyes, even. Alive! She’d giggle. I’d belly laugh. Adam in the garden. The breath of life breathed full-on into my face.

Still, it would be a violation of the opening scene in scripture to underscore human vitality without giving death its due or, by the same token, giving death its due without underscoring the exclamation of human vitality. The unfortunate clash between energy and emptiness, life and death, breath and dust, is an essential ingredient in taking hold of our world, where the giving of life is hemmed in by punctuations of death, like exclamation points in a Spanish sentence, where a single, shared intimate moment between God and adam is bordered by the inevitability of death: dust then life then dust. The opening scene of the human drama, though set in a garden of delight, echoes against the implacable cliffs of the valley of the shadow of death. This is where we start to talk—chatter, really, given how little we grasp—about the spirit. This is where black and blue saints begin to discover God.*

*If you’d like to study this in more depth, see Filled with the Spirit (Eerdmans, 2009), pages 14-15.