In the days prior to that first Pentecost, Jesus’ followers were huddled together, gathered around a single command, a solitary promise. Jesus had told them to wait in Jerusalem for the “promise of the father” (Luke 24;49). So they did.

What would that promise have looked like to them? What exactly were they waiting for? A clue to the answer lies in Peter’s sermon, which he delivers after the upper-room faithful are filled with the holy spirit and speak in other dialects, which scattered Jewish pilgrims from throughout the Roman Empire are able to understand. Peter quotes from Joel 2 (Joel 3 in Hebrew): the spirit has been outpoured, slaves and slave-girls, young and old, male and female can now prophesy.

Peter’s use of Joel provides a pretty good clue to what the earliest followers of Jesus were waiting for. They waited for the outpouring of the spirit. That was the promise of the father.

Joel 3, which Peter quotes, belongs to a collection of promises that God would pour out the spirit. Prior to this, our own Pentecost, let’s look at a lesser known promise of the outpouring of the spirit—in the hopes that we, like Jesus’ earliest followers, can wait for the promise of the father, too.

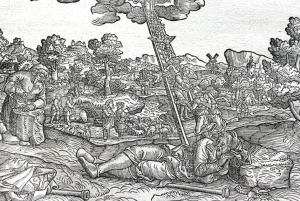

In the earliest of these promises, the prophet Isaiah confronts women who are mired in complacency—whether by their own choice isn’t clear. Isaiah predicts a failure of harvest, the aftermath of a war that will devastate the palace and city. These women, Isaiah urges, should beat their breasts in mourning for the death of their fields and vines.

Nonetheless, impending judgment is met with distant promise. The palace, city, fields, and vines will lie desolate:

… until a spirit from on high is poured out on us, and the wilderness becomes a fruitful field, and the fruitful field is deemed a forest. Then good judgment will dwell in the wilderness, and justice abide in the fruitful field. The effect of righteousness will be peace, and the result of righteousness, quietness and trust forever. My people will abide in a peaceful habitation, in secure dwellings, and in quiet resting places. (Isaiah 32:15)

The advent of the spirit will mean the inauguration of justice.

Like so many promises, however, there is something vague and inexplicable, something unimaginable about this one. How will good judgment dwell in the wilderness, and how will justice occur in fruitful fields?

Shouldn’t justice come to city gates, where men gather to deliberate?

Shouldn’t justice come to palaces, where kings and queens rule?

Not this time. This may just be an image of justice toward workers, a promise of fields with corners left unharvested so that the poor and aliens, like Ruth, can gather their food.

Is Pentecost about migrant workers? Does the promise of the father demand that we work on behalf of the workers who pick and pluck our Pentecost lunches, our strawberries and lettuce leaves? Is that what Pentecost means today?

And the effect of right judgment and justice will be, of course, peace, quietness, lack of fear. There will be, in short, security and stability. In the aftermath of destruction, in the wake of desolation, people will come home. Home will come to the homeless.

Is the promise of the father, the foundation of Pentecost, that home will come to the homeless, to wanderers, to migrants?

Probably. That’s why the outpouring of the spirit in Isaiah’s vision doesn’t happen in sacred sanctuaries, with red-festooned banners, with red-vested priests and pastors, with red-breasted bishops. The outpouring of the spirit, the advent of Pentecost, happens elsewhere: on the edge of desolation.

That’s the promise of the father.