Yesterday a friend’s Facebook post got me thinking about the issue of God and gender. Specifically, does God have it?

The obvious answer is no. God is neither male nor female. This was the reality that my friend was (rightly, I think) trying to get his Christian college theology class to get hold of.

As my freshman year religion professor put it, “God does not have genitalia.”

But that doesn’t really answer the question about whether God has gender. It answers the question of whether or not God has (a) sex.

I want to suggest that God does, in fact, have gender. What Christians debate about is whether this is a good thing or a bad thing, or whether it’s necessary and therefore being done right or therefore needs to be done better.

Full disclosure: I’m about 20% convinced of what I’m about to suggest here. I’d love to hear what other folks think.

Sex and Gender

First, though, we need to know what we’re talking about. The words sex and gender are sometimes used interchangeably. But here’s how the APA and medical community differentiate the terms:

- Sex (male, female, intersex) refers to a person’s biological characteristics such as chromosomes, genitalia, internal and reproductive organs.

- Gender refers to behaviors, attitudes, and feelings that a given culture associates with a given biological sex.

While sex is biologically measurable, gender is always a cultural measure. We have expectations for what a man will do, how he will dress, how he will act. Each culture has its own list of idealized masculinity and femininity. People conform or fail to conform to various degrees.

This also means that one culture’s masculinity might be another culture’s femininity. A North American dude bro who boasts about having sex every night would be thought effeminate in ancient Rome for his enslavement to his body’s passions.

God’s Gender, Human Culture

One of God’s great liabilities is that people are always part of the picture. Well, we tend to think of it as a liability; biblically speaking it seems to be something God quite enjoys.

But in this case the problem is that once people are involved, so are human cultures, and so, then, are our cultural cues about gender identity. For people, there is no “God as such,” there is only God as God is made known in particular times and places. This means that our interpretive lenses are always actively filling in the gaps and creating the narratives.

The standards for what makes a god good, or worthy of worship are always deeply embedded in cultures. The stories of the conquest tell of a God worthy of worship in a world where provision of geopolitical security is the hallmark of a worthy divinity.

The divine warrior God is manliness writ large. Or, perhaps better put: an ancient king is God writ small.

In the New Testament, of course, the most pervasive title for God is “father.” This is a male gender role. When, throughout the history of the church and across the globe, people say, “I believe in God the Father,” we are confessing a God of male gender, even if we don’t believe that this God is an expression of the male sex.

Because gender is a cultural construct, and because our access to God is always mediated through people who form cultures, and because those cultures have typically been patriarchal, the Christian God does have gender and it is typically male.

I think that this is a problem. I’ll talk about why in just a bit. But for now, what about God as God is in Godself?

God Without Culture

There are two problems with appealing to God as God is in Godself as an end-run around the reality that we inhabit.

The first problem is that we don’t have access to any such thing. All we have as what has been revealed. And all revelation is mediated through humans who are embedded in gender-making cultures. This includes the revelation that comes to us in the male-sexed body and male-sexed gender of Jesus.

The second problem that we have as Christians when we want to retreat to heaven is that a set of gendered relationships is waiting for us there: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit–an image of “Father” chosen specifically so that the “Son” can be “begotten” (which men do) without being “borne” and “birthed” (which women do).

God as such might not have a gender, but it seems difficult to claim that the Christian God does not have one.

A Time to Embrace?

The notion that God is male is deeply problematic. Mary Daly has famously said, “If God is male then male is God.” It doesn’t take much knowledge of culture and power both ancient and more recent to know that this is a devastating insight into both the purpose and effect of a male-gendered God.

But it might be too much to ask us to cultivate a God without gender. It might be humanly impossible, and given the gendered God who confronts us in scripture and tradition it might be, more specifically, Christianly impossible.

Might it, then, be up to us to back away from what we might want to claim about God in Godself: “God does not have gender,” and own up to the reality of who we are and who God will always be for us?

We humans will always give God gender and anticipate a corresponding gender expression. So rather than saying, No, what if we say Yes?

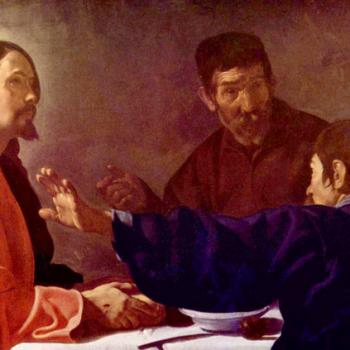

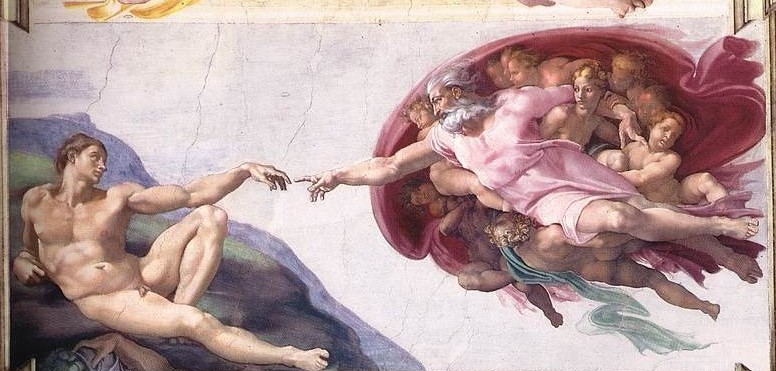

What if we say, Yes, God has gender, and it is both male and female? What if we work toward cultivating a feminine gender identity for God that is as rich and robust and mentally captivating as the yarns and epics that fit within the activity of Michelangelo’s Powerful Old Man?

What if, paradoxically, embracing this cultural limitation might bring us closer to the truth than striving to cast it off entirely in pursuit of a heavenly ideal that would always allude us?