Memorial Day is only some three months away. And we all know what that means. (No, I’m not talking about parents having to take another day off of work for some lame school holiday.) It means summer. It means that if you want to get that perfect “beach bod,” you’ve got three months to get in shape for it.

The good news is there’s plenty of time. Plenty of time to pack on those extra pounds, add those missing curves, so that your body can be the envy of all your friends.

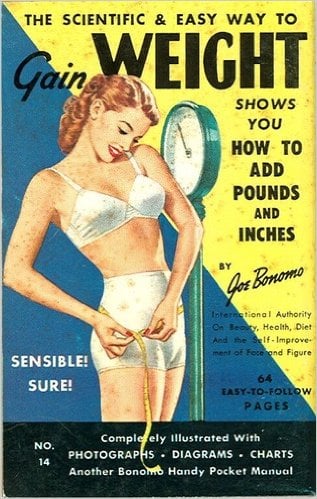

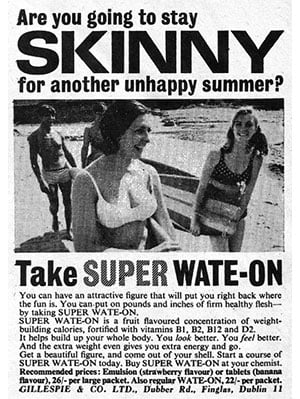

We are so drenched in the worship of the skinny in our current culture, that the existence of “Wate-On” is almost unfathomable to me. And check out this gem of a booklet from 1965 (unfortunately not currently available on Amazon).

There is an easy point to see in these old advertisements. (And by “old” here I mean something that was my parent’s generation, so really not that long ago.) That is this: standards of beauty change. Ok, so that’s somewhat trite. Everyone knew that.

But dig into it a little more. These ads help us see that cultural norms shape our very sexual desires.

When in Rome… Things Look Roman

Spend any amount of time studying sexuality in another culture and you’re likely to find that things you take for granted are not the same in all times and places. What we consider “natural” turns out to be rather particular.

Craig Williams, a classicist who teaches at the University of Illinois, gave this piece of sage advice for interpreting ancient texts:

For “nature” read “culture.”

In other words, what someone sees as natural from within their limited sphere of experience will likely be seen as culturally peculiar from the perspective of an outsider. This might be true for far more than ancient texts. It might be true of many of our perceptions.

For many of us (looking at you, Myers-Briggs Js), one of the most difficult life lessons is recognizing that what we experience or think is not just “what is.” It is our way of perceiving and judging.

Cultures and sub-cultures have this same problem. Corporately we look at things a certain way, judge them by our norms, by things that are completely obvious to us. And we often find ourselves simultaneously judging people whose judgments differ from our own.

When you’re in Rome, things look Roman. When you’re on Fox, things look Foxy.

Back to Sex

Sorry to stray from talking about sex for a second there. I’m back now.

One aspect of life in Ancient Greece and Rome that creeps me out is how Greeks and Romans configure sexuality.

The Greek idea of pederasty (“tutoring” a young adolescent boy for his own training in social goods and graces) I find completely nauseating. It reads to me like the Panhellenic Pedophile Association got together and found a way to make their little perversion into a national virtue.

Ok. So maybe that one’s not such a great example.

But there are other things that make me scratch my head almost as much.

In Ancient Rome it was assumed that a citizen might have sex with any number of people of either gender. A brothel was likely to have both male and female service providers, and the same person would be expected to use either depending on what they felt like on any given day.

Similarly, we see various indications that all slaves were sexually available to their masters, with no judgment being made about whether the slave (we would say) raped (they wouldn’t say “raped”) was male or female.

It’s enough to make me wonder if the working assumption, which lies just beneath the surface of so much popular chatter on sexuality, that “normal” sexual preference is singular and persistent might, itself, be culturally conditioned.

Essentialist v. Social Constructionist

This fall I did some wide-ranging reading on race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. There was one common thread that ran through all the material I studied, and it surprised me a bit.

Generally speaking, each of these fields seems to have gone through a cycle in which they begin their study with the assumption that their topic is an essential, inherent characteristic of the group being studied. But then, be it for reasons of science (DNA doesn’t uphold the notion of “race” as a physiological category), or anthropology (that culture has 7 different gender categorizations), or something else, the conversation moves.

The shift is into a model of social constructionism.

The idea whose remnants (if only it were just remnants) continue to impact us today, that “black skin” signals a different kind of person, is a construct born out of colonialism, the modern transatlantic slave trade, Jim Crow reconstruction, and the subsequent justifications for them. “Race” as we experience and think about it is a social construct.

(You can quiz yourself on this when you think you’re ready.)

Here’s the first thing we need to come to grips with in this essentialism vs. social constructionism conversation: almost every field starts with an essentialist assumption because that is how we experience the world.

The reality in which we live in the U.S., for instance, is one in which “white” or “black” makes a dramatic difference in how a person is perceived, what opportunities and dangers society presents, etc.

For most of us, the sorting of the world into boys and girls at birth makes complete sense based on (what we know of) presence or absence of sexual organs.

But dig a little deeper and we start to see that all facts are interpreted facts. And our culture provides interpretive grids that we are not typically aware of.

“God Made Me Like This”?

As I listen in on the on-going Evangelical Christian debate around sexuality the conversation often presents these two options: (a) being gay is a choice; or (b) being gay is how a person comes wired (“God made me like this”).

I hope that everyone has had enough conversations with LGBQ folks to know that their sexual orientation, like a “straight” person’s, is not a choice. That is to say, “not option (a).”

But…

In reading all of this material about essentialism and social constructionism, I did start to worry that the Evangelical Christian answer to the question of why we should be affirming of people’s sexuality might build too much on the shaky foundation of essentialism. If the whole argument is, “God made me like this and it’s ok,” then you’re probably going to be nuancing it to death in ten or fifteen years.

Because the reality is likely more complicated: We are in a certain culture that has given us a binary option. Most of us therefore end up on one side of the binary. The dispositions and DNA mingle with cultural expectations and expressions of maleness and femaleness in yourself and in reaction to others. We don’t choose to wire our brains, and in the case of our sexuality it is usually not possible to rewire them.

But between “it’s a choice” and “God wired me like this” is a complex set of interactions between our physiological make-up and our social constructs that, in very real ways, construct us. (One of my early shocks was reading Judith Butler saying something along the lines of: I’m not sure I want to be called a lesbian, because that presumes we agree on what one means when calling someone a woman.)

Perhaps this is just a plea, or even a warning, not to pin too much on DNA sequencing, or some other physiologically demonstrable aspect of “being made.” There are lots of ways to imagine being “fearfully and wonderfully made” that aren’t reducible to genetics.

God’s Glory, Still

There is a way that the “God made me like this” argument can fall short. Essentialism is a trap. But there’s another aspect of it that is deeply true. There is no “abstracted from culture” human being or human characteristic that is “what God made,” which brings God glory or delight.

To be human is to be embedded in culture. To express any facet of our identity is to put on display an enculturated reality.

Race and even ethnicity are human constructs. And, the kingdom of God will be incomplete to the extent to which its race and ethnicity fail to embody the fullness of humanity’s racial and ethnic diversity.

Gender and maybe even sex are human constructs. And, the kingdom of God will be incomplete to the event to which it fails to incorporate male, female, and everything in between, into its whole life.

Sexualities are human constructs as well. This does not make them any less bearers of the divine fingerprint.

One of my favorite literal translations is from Isaiah 6. Most Bibles read, “The whole earth is full of His glory.” A more wooden translation is this: “The fullness of the earth is His glory.” The first one means that something comes from God and fills the earth. The second, the literal one, means that something emirates from the earth and conduces to the glory of God.

The fullness is God’s glory.

The earth full of people and places, of cultures that understand themselves and live their lives from within. Peoples and cultures become unique though divisions and categories we make for ourselves and the identities we craft within them. This is all the beauty and the fullness that is God’s glory.

And since we can only ever be who we are within culture, maybe we can even say, “God made me like this.”