On Wednesday I started exploring again the importance of narratives, the stories we tell to make sense of the facts of the world, the stories we tell that create the facts of the world.

Yes, interpretation has the power to create facts.

Sometimes this is easy to see: a people interprets a minority group as being inherently inferior, which leads over time to systematic discrimination and lack of social standing and privilege.

But sometimes it is difficult to see: the notion that “black” is a different “race” from “white” is a modern construct that would not have been immediately intelligible to a first-century Roman, for instance. Our interpretation of skin color as a racial category generated the “fact” that upholds black-white racial categories across much of the (Western) world today.

Four Jesus Stories

One of the most astounding things about the Christian scriptures that we have four different Jesus stories. On par with this for its potential to astonish is that the authors of some of them have thoughtfully and intentionally changed one or more of the others in order to tell a Jesus story that fits its own theology better.

The presence of four Gospels at the beginning of the New Testament is a latent power, waiting to explode our preconceptions of what Christianity must (or must not) be.

You would think that if there were one thing that Christians had to agree on it would be Jesus. And to a degree that’s correct: yes, to be a Christian is to agree that Jesus is critical, that Jesus is the agent and revelation of God, that Jesus accomplishes something in the cosmic story of God’s engagement with the world.

But, wittingly or no, when the church decided to include four Jesus stories it made a permanent statement that no one version of how Jesus is so important would ever be determinative.

This cuts deeply across all of our human instincts. Our tribal instincts have a deep evolutionary history that we always struggle to shake. We need to define our tribe. We need to know who is Other.

Stories and Violence

Harmonizing the Gospels is the first act of violence against the diversity of God’s people.

When we will not let Mark’s Jesus warn us against trying to harmonize the wine of his ministry with the wineskins of Jesus and at the same time allow Luke to remind us that the old wine is better we arbitrarily decide that to be a Christian is to follow our own theological preference. There is a world of difference between choosing a story of Jesus for reasons that we in our time and place find compelling, and ripping out a competing story altogether.

The history of the church is sometimes a story of this very kind of violence. Neither Matthew nor Mark nor Luke would have survived the anathemas of the Councils of Nicea and Constantinople. I’m sure that if I had been at either assembly I would been with the progressive majority, attempting to leave behind the conservative notion that only the Father qualifies as the creator God.

But I take this as an indication that, as usual, God’s capacity for love and embrace is a whole lot bigger than mine.

As someone who has been running in progressive (evangelical) circles for a few years, I wonder if we’ll discover a commitment to a church that’s bigger than ourselves. I find penal substitution as crazy making as the next person, but it makes a lot better sense of Romans 3:21-26 and Romans 5:1-11 than most other models I’ve read (and fits with Jewish martyrological traditions as well). I think there’s room here for Paul and for people who like him.

Is our progressive abhorrence to violence driving us to our own acts of violence toward those who tell the story differently? Is there an escape from the danger of replacing the violence we find reprehensible with the violence that legitimates our own telling of the narrative?

The Surprise of Transformation

What if…

What if the presence of Gospels (Matthew and Luke) that changed another Gospel (Mark) shows us that what we might deem violence to the text (taking its story and transforming it for a different context) is actually the way of peace and unity?

The Gospel that is most different (John) also shows the greatest theological dissonance with the others (in John Jesus is preexistent and revealer of what he knew and heard before he came to earth). But it is also the Gospel that makes the most overt gestures toward the need for unity and even reconciliation.

- There are signs of tension: every time the beloved disciple is mentioned (a character unique to John), Peter is also present. And there is some indication that the beloved disciple is superior or closer to Jesus.

- And yet, in nearly every scene, there is collaboration between these figures or deference or Jesus diffusing what might be a tension. Yes, the beloved disciple is reclining on Jesus’s breast, but it’s Peter who tells him to ask who will betray him. Yes, the beloved disciple outran Peter to the tomb, but it was Peter who went in first. Yes, Jesus says that it’s none of Peter’s business if the beloved disciple sticks around forever, but no, Jesus didn’t say this was the b.d.’s actual destiny.

- The tensions between two different communities are represented. But they are narrated into a shared leadership among the twelve. And this is the Gospel where Jesus prays that his followers on earth may all be one.

Retelling the story, changing the meaning of words and phrases, is what we so often would think of as exercising violence on the text, on the story, or even Jesus himself. But here we have a plea to recognize the opposite: the story with the most profound change begs to be read as a story among the others, its own voice in harmony without being harmonized, in unity without being subsumed.

Renarrating our Story Telling

How we tell stories has the potential to change the facts of the world we live in. Perhaps the most important story we need to revisit is what we’re doing when we tell stories.

No matter where we are on the theological spectrum there is a tendency to vilify the stories that are not our own while lionizing the narratives that come from the mouths and pens and electrons of our own heroes. The points of difference are the identity markers of our tribes. It’s human nature to police those boundaries and raise the alarm when they are crossed. Even if those alarms are only the internal alarms of our fears and anxieties.

But what if we are called to tell the story in such a way that variance is not a sign of infidelity but of honoring and upholding the shared story of Jesus? What if the very presence of four Gospels is supposed to create the fact of theological plurality within the church?

What if the love to which we’re called is as capacious as the love of God who could love Luke no less than John, Paul no less than James, Mark no less than Revelation, Jeremiah no less than Nehemiah, the Priestly writer no less than the Jahwist?

What if…

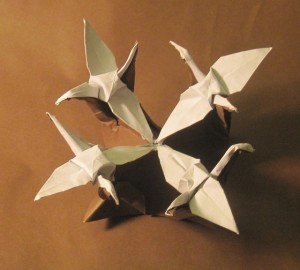

Featured Image “Four Cranes” © Tyler Spaeth | flickr | CC 2.0