“It is hard to be human. It is hard to know what to do. It is hard to know how to take care of those we love. It is hard to give up on our fantasies of immortality, or power, or the thought that if we could shape the world to our will everything would be better.” — One of my favorite bits from what has become an extraordinarily long (and endlessly interesting) conversation with Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik, creator and writer of The Booth at the End.

Joseph Susanka: The series’ tagline — “How Far Would You Go?” — captures the central motivation behind everyone who comes to The Man for help. All of them are driven by a desire for some real good, but the question of how far they are willing to go — how much of their souls are they willing to mortgage to get what they want — is a suspenseful (and often terrifying) one. In Season Two, in “a new diner in a new city with new and unexpected clients,” we’re promised a bit more insights into The Man himself, and the motivations behind his mysterious behavior. What was the idea you were most excited about exploring in this second season, how much will it change the way we view its protagonist, and do you have even more ideas and topics you would like to flesh out in future seasons after this?

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: Well, first, I love all the characters. Always. The show is an anthology series featuring each of the clients wrapped up in the long arc of the mystery of The Man. So, simply getting a chance to get back in that booth and hang out with new characters is something I’m happy to do.

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: Well, first, I love all the characters. Always. The show is an anthology series featuring each of the clients wrapped up in the long arc of the mystery of The Man. So, simply getting a chance to get back in that booth and hang out with new characters is something I’m happy to do.

In terms of pushing things forward, what I care most about is following The Man on his journey. He has an agenda (which I know, even if it still remains a mystery to the audience). In Season Two, I wanted to watch The Man get more involved in the lives of his clients. In the First Season he made a point of not engaging with the people across the table from him. In this season, he does.

Joseph Susanka: You have said of yourself that “I’m not religious by nature. I am religious in my curiosity.” But you also say that Booth is “a very moral show, drawing out of the supernatural New England tradition, going back to Nathaniel Hawthorne.” The series is very much a spiritually searching one, particularly when it comes to The Man’s continual fascination with the impetuses of his “clients” and their struggles between what they want and what they know they should do. (Is he an angel? A demon? Puppet, or the Puppet Master?) Could you talk a bit about the ways in which your own particular thoughts on religiosity and spirituality seep into the show, and how it “puts immoral things in the spotlight to highlight morality and the choices and complexities?”

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: There are several things to talk about here:

Christopher “C.K.” Kubasik: There are several things to talk about here:

The first is that issues of religion, or spirituality, or morality—these are all very human concerns. Even the New Atheists, with their relentless yammering against religion, are engaged in concerns and debates about religion. People have had arguments about God and Faith since humans have been around to have arguments. It’s one of our species’ hobbies.

So, the first thing you need to know is my primary concern as a dramatist is humanity—and religion is part of humanity.

If I’m going to be curious about people, issues of religion and faith will show up. There’s no way around it.

My primary concern about humans is because I’m madly in love with how strange it is to be a human being and how hard it is to be a human being. More than anything else, I consider The Booth at the End a love letter to us… the billions of strange creatures living on this planet, trying to figure out how to get through every day.

I know this might seem strange, given some of the horribleness involved. But the horribleness is not what the show is about. The difficulty of being human is what the show is about.

It is hard to be human. It is hard to know what to do. It is hard to know how to take care of those we love. It is hard to give up on our fantasies of immortality, or power, or the thought that if we could shape the world to our will everything would be better.

The Man’s magic offers everyone a chance to avoid the limits of being fallible, fragile, and mortal. The Man’s offer says, “You don’t have to grow up and accept limitations. You can keep your adolescent fantasies forever.”

The characters that turn their back on The Man’s deals are the characters that learn to grow up.

* * *

The Man is as curious about people as I am.

The Man is as curious about people as I am.

As I imagined him, The Man doesn’t write off anyone. Even people you and I would dismiss out of hand, he’s curious about.

“Why does person hate that person?” “Why is this person willing to kill others because of love?” In this way The Man is, I think, better than the rest of us. He listens to anyone and everyone. He pays attention to anyone and everyone. How many of us could make a similar claim?

He doesn’t presume to have all the answers. He knows he doesn’t have all the answers. That’s why I put The Book into the show—to make it clear he does not have all the answers. To be clear: I do not consider him a “puppet master” at all. If he had all the answers, if he knew everything already, and was handing out tasks knowing how everything would turn out and manipulating people with foreknowledge, he would simply be a sadist of the soul, torturing people with choices that don’t matter. A character like that wouldn’t be very interesting to play or very interesting to watch.

He is in that diner booth because he’s trying to understand who we are and what makes us tick. I think that’s a worthy goal. Which also means, just like the characters sitting opposite him, he is putting people at risk. He is a Robert Oppenheimer of the Soul, splitting open moral choices because there is something he needs to understand. He has an agenda that could blow back at him. And because of that, to me at least, he’s an interesting character—because he is, in part, unable to control his own curiosity in the same way he is unable to control the forces he is unleashing from The Book.

* * *

Let’s assume for a moment that by the word “religion” we mean very many things.

Let’s assume for a moment that by the word “religion” we mean very many things.

If we look at the notion of religion outside the tradition of trying to control other people or treat people as “the other” (which is how religion is often used, by the way), one thing you are left with is a wrestling with the strangeness of being alive as a human being. Because here is the truth: We are frail, mortal creatures filled with tremendous dreams and ambitions. There is a gap there. And that gap is hard to fill. And I believe that gap is where a lot of our troubles come from.

We are mortal but have dreams of immortality. We are doomed to frailty but want to only grow in strength. We are trapped in finite containers of bone and blood but in our dreams and fantasies we think we can be infinite.

When I look at religious texts I see, yes, the power fantasies and desperate tribalism that religions often become. But I also see comfort and succor to those willing to realize we can’t have it all—and that we’d simply make a mess of things if we could.

Moreover, religious texts also say, in one-way or another, “Even if you are limited, even if you are mortal, you are enough. You are human, and alive, and capable of love. And that is amazing. You are part of something larger than you can fully conceive. Honor that, love that. Treat each other with well.”

* * *

A final point on this matter. David Foster Wallace wrote:

“In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.”

Now, while this quote probably enrages atheists who will insist they worship nothing and will demand a debate about the word “worship”—the quote makes perfect sense to me. And it certainly makes sense in the context of The Booth at the End.

Every character that goes to The Man is making choices about what he or she will worship. The struggle of what to worship is, in part, what the show is about. My point is the choice of what to worship is difficult and worthy of examination.

Parts I, II, and III can be found here, here, and here.

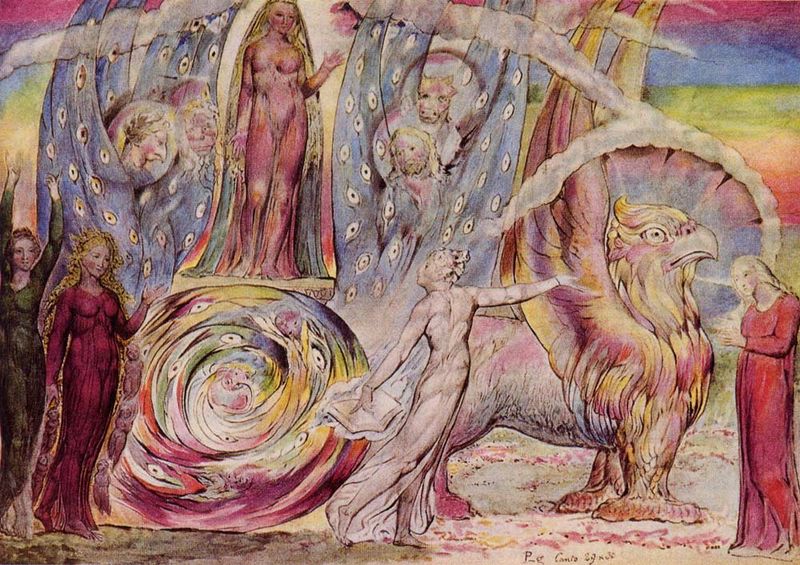

Attribution(s): Publicity images and film stills are the property of Hulu and other respective production studios and distributors, and are intended for editorial use only; images of Mr. Kubasik were provided by C.K. himself; “Beatrice Addressing Dante” and “The Tower of Babel (Vienna)” by Pieter Brueghel the Elder are both licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.