Whose side were you on in the scandal that erupted over Indiana Senate Bill 101, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act? When Gov. Pence signed the bill he insisted that all it did was prohibit state or local governments from “substantially burdening a person’s ability to exercise their religion”. Americans are all over freedom of religion, right, so what could be the problem? Well, claims and counter-claims of persecution went up on all sides as politicians scrambled to amend the law. In the furor, all sides were claiming to be the victims while accusing their opponents of persecution.

When Raven board member, Tripp Hudgins, posted a plea for understanding on his Facebook page this week, he stumbled into the highly charged search for the real victim. He posted an article from Stream.org by John Smirak who feels vilified for standing against same-sex marriage on the basis of his Christian beliefs.

Sample the hate that has been spewed at the state of Indiana in the past week, and faithful Christians in recent years, by gay activists and their allies. We are “bigots,” “Neanderthals” and “haters,” whose views must be ritually rejected by anyone hoping to keep a job in today’s America — even in a Catholic high school. Where will this end? Is there a logical stopping point for this aggression, where Christians are left in peace?

He went on to explain that he feels so persecuted by “the media, the law and our elite institutions” that he fears becoming the target of state sponsored violence and mass slaughter. While in no way endorsing the author, Tripp nevertheless asked that we – those of us who feel that Smirak’s brand of “faithful Christians” are the persecutors and not the victims – that we make the effort to understand his fear. Tripp’s plea elicited many thoughtful responses and a remarkably civil conversation for what was taking place around this issue in other social media venues.

My Enemy, My Self

What struck me was that that the main focus of the comments was around trying to identify the real victim of persecution. Here are a few comments:

If it wasn’t LGBTQ it would be something else. People just love to feign outrage and play victim.

Nobody but NOBODY plays the persecution card like the privileged Christian.

Calling religious people idiots is not meaningless, it’s bigotry.

Siding with real victims meant opposing those who were feigning or making false claims of victimhood. Finding the real victims means that we have truth and justice of our side, which gives us permission to persecute the persecutors. And so the scandal churns – everyone is a victim and no one admits to being a persecutor.

When we are caught up in a scandal, we are in a relationship with our enemy that we would rather deny than acknowledge. Knowing our enemy is a backhanded way of knowing ourselves. It works like this: If you are the persecutor, the wicked and wilfully hateful one, then what am I? By default, I am the victim or the victim’s defender. If we get stuck along in the surface of a scandal, our sense of ourselves as good people can become dependent on finding and opposing an enemy other. As Jeremiah Alberg brilliantly explains in Beneath the Veil of the Strange Verses: Reading Scandalous Texts, if we are to find our true selves we need to be careful “to avoid being entrapped (by the fascinating surface of scandal) and thus lose the opportunity to ‘get beneath the surface’.”

Beneath the Surface of Scandal

So how do we get beneath the surface? Here was Tripp’s advice for those of us who are scandalized by Christians who

have been taught that they are a persecuted people. Their entire world view is predicated on a Christology and Ecclesiology of persecution. As a fellow Christian, I am called to love them. So, when I am tempted to go get a pointy stick, to show disrespect, I stand on the slippery slope of dehumanizing them. I think they are wrong and misinformed, but I am called to love them no less. I say this as a pastor whose first wedding was a same-sex wedding more than a decade ago. I have been an advocate for LBGTQ inclusion my entire adult life. The only way I am able to do this work is to find some way to understand the hearts and minds of the people with whom I disagree. (italics are mine)

“As a fellow Christian, I am called to love them,” Tripp said. But how do we honestly love someone we believe is a persecutor? How do we follow Jesus’ command to love our enemies? We can begin by acknowledging the relationship with our enemies that links us at the level of identity. The command to love is a command to shift the quality and substance of that relationship.

Love is more than respect, more than tolerance – love involves a willingness to be changed by and in the presence of the other. Unless we are that completely open and unguarded, that willing to be wrong and to be forgiven, our love is hollow, nothing more substantial than an act impelled by the threat of legal action.

To love a fellow Christian who feels persecuted might mean to take seriously their fear of becoming victims of violence right here in the U.S. Is it possible that our dismissive antagonism towards that fear is actually fueling it? That’s the kind of humility that love requires.

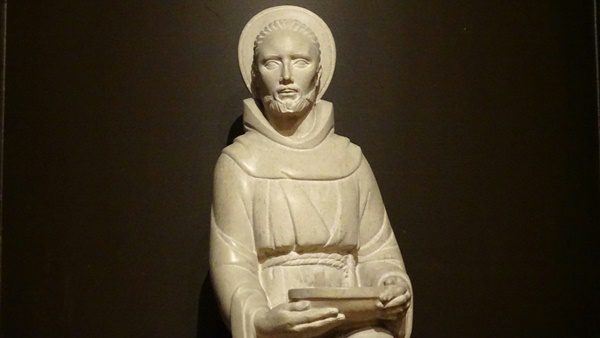

Only love has the power to move us beneath the surface of scandal. If we truly want to protect victims from persecution, we need to doubt our own conclusions long enough to wonder if we have become persecutors ourselves. What side did you take in the scandal? Perhaps we can all try being on the same side, the side where we are all a little bit wrong, a little bit prone to self-justification, and a little bit violent. When the real victim stands up, none of us wants to find that we have been his persecutor.