Crystal Mason’s Story

I showed my kids that no matter what you can get out and get your life in order. But sometimes, regardless of whatever your past is, you are still going to be beat up for it. – Crystal Mason

In a just and compassionate nation, Crystal Mason’s story would – in its entirety – be one of resilience and redemption. It started out that way. Upon leaving prison, where she served 3 years of a 60-month sentence for tax fraud, she was reunited with her children and extended family. She found a job, and became a primary breadwinner for a large household, including her children and some of her nieces and nephews. She worked hard not only to support them, but to model for them a life of perseverance and beating the odds. It seemed, for a short while, like she was on her way to a better future.

All of that changed on Election Day 2016, when Ms. Mason walked into a voting booth in Fort Worth, Texas, and cast a provisional ballot before the term of her supervised release had expired.

In a just and compassionate nation, she would have been within her rights to do so. Many other democracies around the world allow for inmates to vote. But in the United States, Ms. Mason is heading back to prison… for casting a vote that was never counted.

Ms. Mason claims that she did not realize it was illegal for her to vote. After all, Texas is one of several states that restores voting rights to those who have completed their sentences. At the time she cast her vote, the “supervision” of her supervised released consisted only of checking into a website to confirm that she had not been arrested. When she went to cast her vote at her polling place, she found that her name had been purged from the rolls, but was told that she could cast a ballot and, if she no longer belonged on the rolls, it would not count. She figured there was no harm in trying.

Over four months later, she was arrested and ultimately sentenced in state court to another five years in prison for voter fraud. Additionally, last week she was sentenced in a federal court to another ten months of prison and over 2 years of probation for violating the terms of her release. This is all despite the fact that her lawyer maintains that the crime of voter fraud must be committed with intent, and her supervisor testified that he did not instruct her that she could not vote. Ms. Mason and her lawyer contend that her vote was a mistake, not a crime.

I contend that it should be neither.

Racism

Ms. Mason’s punishment for a vote that was never counted is heartbreaking and infuriating not only because of its excessive cruelty. It is blatantly racist, and it undermines what democracy is meant to be.

Racism can be suspected in Ms. Mason’s case due to the fact that African Americans are more likely to be convicted of crimes and to serve longer sentences than white people. Had Ms. Mason been white, she may have received more benefit of the doubt that her vote was a mistake rather than an intentional illegal action. Then again, had she been white, she may have received a lighter sentence for her first crime, and thus have completed it by November of 2016, making her vote completely legal. Yes, this is speculation. But it is speculation based on recognition of the deep, systemic, foundational racism that built a nation on slavery and segregation. It is speculation based on the consistent discrepancy between the conditions and treatment of African Americans versus white Americans.

What is not speculation is that in Tarrant County, TX, where Ms. Mason voted and was sentenced to five years of prison, a white man named Russ Casey, a justice of the peace, actively committed a different kind of voter fraud and received a much more lenient penalty. He forged signatures in order to put his name on a ballot, arguably a far more serious and consequential and unmistakably intentional crime. He pled guilty, and received a $1000 fine and five years’ probation, with the condition that he refrain from seeking a government office again.

That the same county could seek to imprison a black woman for a lesser crime than that of a white man – a judge who understood the law better than a lay person could be expected to – is unmistakably racist. And it comes in the context of the first national election since the gutting of the Voting Rights Act, which has had a detrimental effect on minority communities around the country. Kim Cole, Ms. Mason’s lawyer, contends that Tarrant County is making an example of her client in order to intimidate minority voters. Because Texas has closed over 400 polling places – more than any other state in the nation – since the Voting Rights Act was scaled back, I am inclined to agree.

Given that African Americans are convicted at higher rates and given harsher sentences than white people, a penalty so resoundingly severe for an unintentional and inconsequential infraction sends a strong message to previously-incarcerated voters, particularly minorities: “Don’t even try to vote. If you make a mistake, we can end you.”

Mocking Democracy

Many who balk at the harshness of Crystal Mason’s sentence nevertheless would contend that voting restrictions for people who have been previously incarcerated are reasonable. Many would argue that the seriousness with which society treats voting in the United States can be seen in how this privilege can be lost upon committing a crime. For many, exclusion gives a veneer of value. The more expensive or difficult to attain or hold onto, the more precious it must be. The more voting is limited to those who have proven themselves responsible by societal standards, the more meaningful it is, some would argue.

This is not true.

Voting is most meaningful when it is open and accessible to every of-age citizen, regardless of past mistakes. Democracy – governance by the people – should recognize that people are fallible but also redeemable, and no one’s ability to take part in the choices that affect themselves and their loved ones should ever be permanently rescinded.

To disenfranchise those who have committed crimes, as some states do permanently, is to deny the fact that humanity is always flawed and yet always redeemable. It is to perpetuate the popular but false myth that “criminals” are akin to a separate species, permanently divided from the rest of humanity. The truth is, we all mess up, and we all do wrong mistakenly and sometimes intentionally. Furthermore, there are crimes that hurt no one and yet are punished, and legal actions that can hurt many but have no punishment. Consequences for crimes should be aimed toward compensating victims and restricting offenders from further offending while they undergo rehabilitation, but they should not strip away all of a citizen’s political rights. A democracy truly concerned for the welfare of all its citizens would not silence anyone, even as it imposes appropriate consequences when necessary.

Disenfranchising those who have committed crimes makes it more likely that elected officials will be less aware of or less concerned about conditions that lead to crime and recidivism, as well as conditions of prisons and injustices in the criminal justice system. Systemic issues that contribute to poverty and crime are exacerbated, and those who work for dignified treatment of the incarcerated, including prisoners themselves, are handicapped. Loss of voting rights further stigmatizes prisoners in the eyes of society.

A more humane rehabilitation system would do just that – rehabilitate. An excessively punitive system teaches people that they lose their value upon entering the criminal justice system, which makes them less likely to be viewed respectably by potential employers, more likely to live in poverty, and more likely to return to prison. Retaining voting rights – with possible exceptions under extraordinary circumstances – would mitigate some of the systemic issues that lead to crime by reducing the stigma against the incarcerated and incentivizing public officials to help mitigate conditions that can lead to crime in the first place.

In the case of Crystal Mason, many years of prison and multiple felony charges will hurt not only her, but also her children and the nieces and nephews she cares for. Children suffer the punishments of their parents and caregivers, and in this case, like so many others, the punishment for neither party is warranted. This is how systems of poverty become ever more deeply entrenched.

Restoring Justice

Crystal Mason’s time in prison is scheduled to begin just after a massive, wide-spread prison protest draws to a close on September 9th. Prisoners in at least 17 states are striking from work and/ or going hungry in order to demand more humane prison conditions and voting rights restored. In their list of demands, prisoners are standing up for their irreversible human dignity. They are working for a system that will allow them humane conditions within prison walls and the best opportunity for a future on the outside.

For the sake of Crystal Mason and so many others suffering excessive punishment, for the sake of affirming the unalterable worth of every human being and declaring our faith in the power of redemption, and for the sake of communities across the nation that are better served when conditions that create crime are mitigated rather than exacerbated, I and I hope others will commit to hearing and amplifying their concerns. I pray for restorative justice for Crystal Mason and the system that failed her, and I pray for mercy upon all of us fallible but invaluable human beings.

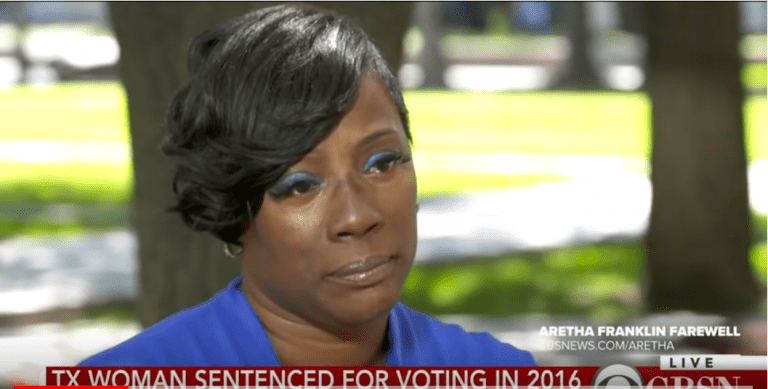

Image: Screenshot from Youtube: “Texas woman sentenced to prison for voting in 2016,” by CBS News