I really like the way Simcha Fisher analyzes this painting, “The Adoration of the Magi” by Tai-Shan Shierenberg.

Is it a problem that these “Magi” are not kings or wise men, that they’re not even all men, that they don’t have historically accurate clothes or hair, or that they don’t show any signs of bearing gifts or of having traveled afar? Not necessarily. These departures from more traditional art may irritate or perplex you, but they aren’t enough, in themselves, to disqualify this painting as religious art.

The reason I call it a secular painting is because it kind of . . . doesn’t have God in it. The Magi’s faces take up most of the canvas; but that’s not what I mean. I mean is that this painting is about the “Magi” themselves, and not about God. A depiction of the Adoration of the Magi might have all sorts of elements in it, but it absolutely must contain at least an indication that what they are adoring is God. This is what is lacking in this picture, and that is what makes it not religious art.

You can tell by the shadows and highlights that the light source is above and to the right, out of the frame. . . In a traditional piece of art depicting the Magi, the light would be emanating from below, from the Christ Child, or from above, from the divinely-appointed guiding star. In this painting, there is a significant break: the light — late morning sunlight, from the looks of it — is from above, from behind the faces, and to the viewer’s right. And it’s pretty clearly just the sun. Why this innovation, if not to make a point?

Read the whole thing; I agree with everything Simcha says, and I would add that in some respects this painting reminds me of some of the particularly “we/us-oh-yeah-you-but-mostly-we/us” centered songs that we use at Mass. Let me take pains to say I do not dislike all modern Catholic music, but a great deal of it is execrable, and in this case I’m thinking of a song like the we/us-fest that is “Gather Us In.”

We are the young – our lives are a mystery

we are the old – who yearns for you face.

we have been sung throughout all of history

called to be light to the whole human race.

Gather us in the rich and the haughty

gather us in the proud and the strong

give us a heart so meek and so lowly

give us the courage to enter the song.

That’s no more a “hymn” than this painting is religious art, and in both cases, the instructive edge that should accompany what is transcendent in sacred music and sacred art has been damped down in order to serve a refocusing, away from God and toward ourselves.

Part of this is simply a response to the Post Vatican II attention to enlivening the horizontal aspect of Mass, the unintended consequence of which was to under-emphasize the vertical. Ideally, the two should be in balance — a representation of the cross — and as I note in discussing this hymn:

Oh, God, by this commingling

of water and of wine

may He who took our nature

Give us His life divine… it was one of those great hymns that provided catechesis; it accentuated and defined the vertical and horizontal aspects of the mass, while having the beneficial effect of adding to the sense of reverence, awe to the most solemn part of the mass, when earth and heaven are joined in Christ, and communion and community all support it. And it joined our prayers to the priests in a profound way — who sings prays twice — and that is part of community, too, and dare I say it, unity.

Instruction is missing in our religious art and music. We might look at a modern song and think, “nice melody, not impossible to sing and it sure makes us feel good about us” or we can look at a painting like the “Adoration” above, and appreciate it for its fine technique, but meaning has become muddled, and too often there seems to be no real center beyond ourselves — room for God in between the borders of the canvas, or the codas on the staves.

We are a culture that takes pictures of our meals and puts them on Facebook; takes endless snapshots of ourselves doing nothing at all noteworthy, and shoots them off to friends; watches meaningless reality-tv for purposes I don’t even understand beyond the “we/us-centricity” paradigm.

Form follows function. Religious art, whether painted or sung, is formed to follow the function of worship, which is the praise and attempted knowledge of God. In much of our Modern “religious art” we can see — as with these examples — the pieces being formed to follow the function of our cultural idolatry.

We cannot see God in our paintings, or find him in our songs, because we have crowded him out — or more accurately, we have obliterated him by the fore-placement of the shiny idol of ourselves, ourselves, ourselves, in order that we may see us, puny us, endlessly mirrored back in our direction.

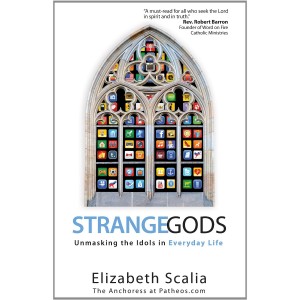

As I note in my upcoming book, we love our Strange Gods, and create them non-stop. But we don’t have to.