As with the Martyrdom of St. Charles Lwanga and his companions we today remember a group of martyrs whose story is not nearly as well-known as it should be. And as with Lwanga and the Ugandan martyrs, the martyrdom of the Carmelite nuns of Compiègne speaks urgently to our own age, and offers instruction:

After the fall of the constitutional monarchy and the execution of King Louis XVI in 1792, Maximilien Robespierre created rituals to honor the Cult of the Supreme Being even as he led the Committee of Public Safety and the Reign of Terror from 1793 to 1794 — dedicated to eliminating enemies of the Republic.

The Carmelite nuns of Compiègne were just such enemies, although all they wished to do was remain true to their vows to pray, live and work together in a cloistered community. In Robespierre’s view, these nuns were counterrevolutionaries.

Say “French Carmelites” and some people will equate them with the Virgin Martyrs, but not in the excellent way they ought; instead, they will roll their eyes and say something about “mewling, simpering, weak women who hold us back” and they will be exactly wrong. The Virgin Martyrs of the early church were warriors and some of the bravest saints in our canon, because they were willing to face down a society that held them as little more than chattel, to be bartered off for land or connections, and declare themselves as emancipated in Christ and belonging to him alone; they took control of their own destinies and were living, breathing signs of contradictions to the prevailing culture. No wonder they confounded so many as they chose death over a life of compliance, no wonder they converted so many, too.

These Carmelites of Compiègne were a sign of contradiction, too, against a trend of raging secularism and a government that shouted “liberty” with one breath and “be silent” with the next, all while applying a boot to the necks of any who dared to continue talking or living in a manner “incorrect” to the times. Yes, they should speak to us today; in fact, they are shouting at us.

For me, personally, they have been a sign of contradiction in another sense, as well, particularly as we watch people make imagined victims of themselves because they think they’re being “denied” things that are no one’s “right” — the fantasy, for instance, that one must wear a Roman Collar and have a pulpit in order to have any power or priesthood in the church. The history of the church has given lie to the prevailing narrative that “the church suppresses women” which is demonstrably false. Like countless women before them, martyred or not, the Carmelites of Compiègne were magnificent priests; they happened to wear privileged collars born of sharpest steel. Their lives and deaths challenge us to better-understand what we lose when we get too caught up in clericalism to recognize the collars we are already offered, and need only consent to wear.

I wrote about that in this column for The Catholic Answer:

What was beginning was [Catherine de Hueck’s] priesthood. She spent the rest of her life championing the oppressed, the poor and marginalized in America’s ghettos, and preaching the Gospel so unapologetically that she was pelted with rotten vegetables. “Preach the Gospel without compromise,” she would say, “or shut up.”

The Carmelite Martyrs of Compiègne remind me of de Hueck. Offered enticements to compromise, they refused. Dispersed and de-habited, they quietly continued their subversive activity of prayer and worked out their priesthood, “preaching” all the way to the guillotine. They didn’t shut up until the blade fell. Our disoriented modern sensibilities equate nuns with meekness, not strength; it discounts the power of their priesthood (and the priesthood of all laywomen) because it is informal, unadorned. For some, priesthood is a prize of attainment rather than a surrender to service — a right to be won, rather than a gift bestowed. Unless their preaching is done from behind a pulpit, they think, it is devalued and illegitimate.

Catherine de Hueck might have called the pursuit of female ordination a distraction and a waste of opportunity when there is so much to be done, when we are all called and the work of our priesthood is already before us. The Carmelites of Compiègne understood this, as did St. Catherine of Siena, Dorothy Day, St. Teresa of Avila, Elisabeth Lesuer and Sister Dorothy Stang, none of whom waited for someone to hand a priesthood to them.

What is your collar made of?

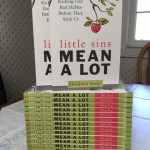

Both of the pieces excerpted here come from the same issue of OSV’s award-winning Catholic Answer Magazine. If you’re not subscribing to it, you really should, particularly if you have tween and teen kids; it is an excellent resource, and perfect for keeping just “lying around” in places where kids get bored and will pick up anything to read.

Related:

Dialogue of the Carmelites