Sometimes I feel like I must be missing some kind of Jewish gene that enables so many other liberal Jews to comprehend ideas that seem completely meaningless to me. This is how I felt while reading the Forward’s latest installment of “Godology,” a conversation between columnist Elissa Strauss and Scott Perlo, a Conservative rabbi. “Godology” is a monthly series “in which they explore what it means to be ‘Godish’ – to kind of, sort of, believe in God.”

The first thing I did was to Google “Godish.” I feel so lost when I read these kinds of exchanges that I wanted to make sure that I wasn’t also missing out on some brand-new exciting theological trend. Unfortunately, the internets have not heard about it. A search for “Godish” got me only as far as Dish TV (“Go Dish!”).

Their back-and-forth dealt with one of my favorite topics: the meaning of the Torah. Elissa asked how – given that we more or less know who wrote the Torah, why, and under what circumstances – she was supposed to celebrate Shavuot. After talking about the basic irrelevance of the holiday’s meaning for her, she tells Rabbi Perlo:

…this isn’t to say that I don’t love the text, because I do. It’s just that, for me, its gravitas comes not from divine-inspiration, but from our attempt to infuse it with divinity for so long. Basically, it feels holy because we have used it to pursue the divine for so long – not because it was divinely inspired.

Rabbi Perlo acknowledges the fact that the Torah is a composite text. He even recommends Richard Elliott Friedman’s Who Wrote the Bible? Yet somehow, even in the face of this acceptance, he can still say this:

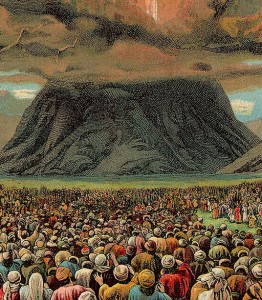

… it is our ancestors’ [emphasis in original] best attempt to communicate what happened at Sinai. I believe, as an aside, that the Divine did reveal itself to us at Sinai, and that the Torah is our attempt to capture the experience and the intent.

If you’re going to accept the findings of biblical criticism and archeology, you cannot simultaneously believe that there was a revelation at Sinai. It did not happen.

He goes on to talk about the importance of “Oral Torah,” the interpretive process invented by the ancient rabbis which they claimed to be a parallel Sinaitic revelation. This process of interpretation, also known as midrash, was the rabbis’ way of projecting their values onto the text. I understand that this is religiously meaningful to him and most rabbis, but for me and many other modern Jews, this process does not make the study of Torah and other Jewish texts more compelling.

I don’t mean to say that studying Torah is not interesting. It is profoundly interesting because in a certain kind of way it is revelation. Not revelation of God’s word. Revelation of how our ancestors – philosophically and scientifically unsophisticated though they were – teased meaning out of texts that they believed were divinely inspired. This has historical significance. And it is the reason why I spend so much time on these texts. (I teach many classes about the Jewish interpretive process and about who wrote the Bible and why.) It informs us about the past in some very significant ways.

It is the practice of using these texts to find answers to our modern-day questions that eludes me and so many others. The rabbi explains how it works for him:

…I think that not to seriously, reverentially incorporate our historic spiritual connection into contemporary spirituality is, well, to somehow cut off the new buds from the roots. But more to your question, I think that reading, for Jews, is a fundamentally holy act. Many people meditate, many pray, but in Judaism, reading is reverence. Interpretation itself brings us to God.

I agree with him that reading is very important to Jews and knowing these texts really can help us feel connected to our roots. Amos Oz and Fania Oz-Salzberger wrote eloquently about this in Jews and Words, a book about how secular Jews might appreciate our literature. What confounds me is this rabbi’s desire to play in a pre-modern sandbox as if we were pre-modern people.

Literature has the power to transform our ways of seeing the world. Whether we are reading fiction (like the Torah) or tendentious history (like much of the rest of the Bible) ancient literature helps us understand who came before us, what they considered important, and how they dealt with their own very different realities.

But I think we actually demean our ancestors and ourselves when we infuse our literary treasures with the magical “Divine” power to guide our search for answers to the big questions of our day. Are they going to teach us how our society should relate to women? To lesbians, gays and trans people? Are they going to teach us the importance of proper sex education? Will they help us to understand how to construct fair and equitable economic systems? To save our environment? To fashion a sensible foreign policy for our nation?

We have before us many more relevant paths to travel as we consider these questions. The answers will not be found in the stories and interpretations of ancient Israelites or the rabbis who succeeded them. Maybe it’s because I’m not seeking closeness to God, but I really do think that we could generate a lot more interest among contemporary Jews in learning about Torah and other Jewish texts if we taught them as the wonderful artifacts of history that they are and stop trying to dig meaning out of them for 21st-century Jews.

I wonder if any of these modern rabbis with their acceptance of the sole human authorship of these texts ever stop to consider that they’re employing the wrong educational approach, at least for many people. I know that they look at the polling data on how Jews feel about “religion.” So why can’t they embrace an alternative? Even if such an approach doesn’t serve their own need for “reverence,” what they are doing is obviously not working for a lot of Jews.