Co-authored by Dr. Kate Kingsbury* and Dr. Andrew Chesnut

He only appeared two years ago but Mexico’s newest folk saint is already being condemned by the Catholic Church in Mexico as worse than Santa Muerte. The Holy Child of Huachicolero (Santo Niño Huachicolero) appeared out of nowhere on social media in 2016 and has caused such consternation that both the Archbishop of Puebla and more recently, the Archdiocese of Mexico have rebuked the surreal folk saint as worse than Santa Muerte because it’s a blasphemous distortion of the Christ Child Himself.

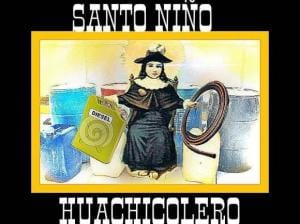

The anonymous creator(s) of the controversial folk saint slightly altered the image of the Holy Infant of Atocha, a well known advocation of the Christ Child in Mexico, switching out his iconic staff and flowers for a gas can and siphon. Gas cans and siphons are tools of the trade for huachicoleros or gasoline thieves who look to the folk saint for protection from both law enforcement and pipeline explosions, such as the recent one in the state of Hidalgo that killed dozens, including children.

Readers unfamiliar with the intriguing Mexican religious landscape might be wondering about the term “folk saint.” Despite having the world’s second largest Catholic population and second most Catholic nation in Latin America after Paraguay, Mexico, like much of Latin America, is home to scores of grassroots saints that are not recognized by the Church but are considered miracle workers by their millions of devotees. By far the most popular Mexican folk saint is Santa Muerte or Saint Death who with an estimated 12 million devotees is now the fastest growing new religious movement in the West.

The Mexican Skeleton Saint, however, differs from other folks saints in that devotees view her as the personification of death itself whereas the others were all real or imagined Mexican men and women who experienced tragic, often violent, deaths, such as Jesus Malverde, the original “narcosaint” whose statuette recently appeared alongside the defense team of notorious narco kingpin, El Chapo Guzman whose fate is currently being decided by a jury in New York.

One might think that with some 10,000 Catholic saints to choose from Mexicans could find one or two to satisfy their spiritual needs. The problem, however, is that most of the canonized saints are Europeans who lived centuries ago and don’t necessarily resonate with the spiritual needs and preferences of 21st century Mexicans (and Latin Americans in general). In contrast, the folk saints are made in the image of their working class devotional base and are thus often viewed as more accessible and approachable.

Veneration of the Holy Child of Huachicolero coincides with an escalating gas crisis in Mexico. In many parts of the country, from Guadalajara to Veracruz, there has been a shortage of gas at stations, with motorists unable to fill up their tanks. Some of Mexico’s most notorious cartels have ostensibly been involved in clandestinely peculating from pipelines that transport fuel. In a bid to overcome this, the government has re-routed distribution via trucks. However, this has entailed long lines at gas stations due to delays in deliveries of fuel. Furthermore, due to shortages in the last two years, gas prices have gone up 31%. Driving has almost become a luxury, far from affordable for the numerous Mexicans that earn under $7 a day, when it costs $40 to fill up a 10 gallon tank of a small car, such as a Nissan Versa.

For thieves, this shortage has provided an opportunity, catering to people’s desperate need to acquire fuel at reasonable prices. They pilfer and sell gas and in turn are able to substantially supplement their meager income. Some also purloin petroleum out of desperation so that they can afford to keep driving their vehicles, transporting their families or merchandise as their needs require. Gas thieves turn to the Holy Child of Huachicolero, propitiating him for protection from the police whilst they are out siphoning. They also supplicate Santo Niño Huachicolero to avoid fires and explosions in the places where they secretly store the fuel, and protect their families who may live close to, if not in that very same locale. They may also pray for protection of children who are often involved in pilfering activities. Children often take the role of juvenile sentinels who watch out for the police or other authorities whilst parents siphon and collect the fuel.

La Cultura Huachicolera, as Huachicolera culture is known, is so deeply ingrained in parts of Mexico that not only do Huachicoleros, gas thieves, have their own saint, they also have their own songs, such as ‘La Cumbia del Huachicol’ (the dance of the gas thief) by Tamara Alcantara, which was a hit on Mexican airways a couple of years ago. With gas prices remaining high, periodic fuel shortages and most Mexicans employed, if at all, in low-paying jobs the Holy Child of Huachicolero, despite the obloquies of the Mexican Church, will likely continue to be venerated nation-wide until all the factors compelling gas thieves and those who purchase their discount fuel are obliterated. This is not likely to happen any time soon. Meanwhile the popular refrain ‘vamos a huachicolear’ (let’s steal gas) will continue to be heard across Mexico.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford, where she also did her Mphil. Dr. Kingsbury is a polyglot fluent in English, French, Spanish. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. She is fascinated by religious phenomena, not only in terms of their continuity across the Holocene and into the Anthropocene but equally interested in the changes wrought to praxis and belief by humans ensuring the infinite esemplasticity that is inherent to all religions, allowing for their inception, survival, alteration, regeneration and expansion across time and space. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda. Follow Dr. Kingsbury on Twitter