‘My name is Death: the last best friend am I’. Robert Southey, 1816

‘My name is Death: the last best friend am I’. Robert Southey, 1816

Co-authored by Dr. Kate Kingsbury* and Dr. Andrew Chesnut

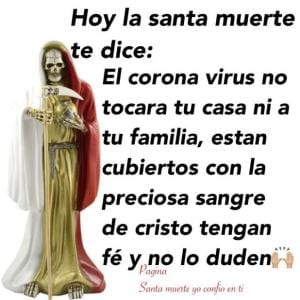

As Santa Muerte cards circulate in Mexico with prayers of protection against covid-19, we consider the contours of life and death in these tumultuous times.

Many countries across the world are now in lockdown or a state of emergency due to Coronavirus, as governments and citizens, gripped with fear, seek to attenuate the virus’ reach. The panic and paranoia over the pandemic are the result of fear of severe illness, and death. Although all living beings must inevitably perish, across the ages, humans have seldom been able to accept their mortality or that of their loved ones. They have invented mythological figures, like vampires who never die, to wallow in fantasies of eternal life. As we watch the numbers of those deceased from Covid-19 increase on television, computer and phone screens, we are constantly reminded of our own ephemerality and the fact that our loved ones will all expire sooner or later. And many, even the agnostics amongst us, are appealing to higher powers to protect themselves and their beloved from the latest threat to our existence.

Death Negative

In the U.S., Canada, England and countries across Europe such sudden and obtrusive loss of life is shocking. For most, demise is a taboo topic and it is only recently with the advent of death positive movements, such as ‘The Order of the Good Death’ that a handful have begun to address their mortality in a more affirmative fashion. Nevertheless, for many in Mexico and other Latin American nation states, death is accepted as part of life and has been for millennia. For Christians, the skull has long been associated with the brevity of life and the fear of demise. Memento mori motifs not only serve as a reminder of the fleeting nature of life but as an exhortation to an ascetic lifestyle punctuated by regular prayer to avoid the punishment of hellfire. The death positive movement has led to a resurrection of memento mori practices among many young Catholics, such as Sister Theresa Aletheia, “the Memento Mori nun” who keeps a skull on her desk as a constant reminder of her own mortality and tweets prodigiously about it.

Death and Duality

In much of MesoAmerica, the skull was a sign not of impermanence, but of earthly rebirth and of the duality and interdependence of life and death, and indeed death and power. The dead in Aztec culture transferred their life force into the land upon their demise, fertilising it and also strengthening the state and its inhabitants, thus ensuring the survival of the living. As such death was not about abrupt endings, as it is in much of European and American culture, but about continuity, community and the cyclical nature of the cosmos.

Given this backdrop and the quotidian violence that plagues much of Latin America, it is little wonder that Santa Muerte, the female folk saint of death, is one of the most important religious figures of the 21st century, venerated by at least 5-6 million Mexicans and many more across the Americas and even some in Europe. The Skeleton Saint is petitioned to prolong life but also provides a cultural framework within which to accept death’s bony embrace should she appear with her scythe in hand to reap one’s last hour.

Santa Muerte, Salubrious and Mortiferous

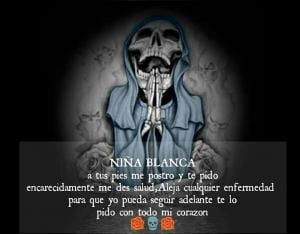

Votive candles with the Saint’s cadaverous motif feature supplications and symbology that appeal to her for both life and death. Devotees may seek the saint’s supernatural services to visit eternal darkness upon an enemy. For example, they may employ the black candle of death inscribed with ‘Muerte contra mis enemigos’ (death to my enemies). And during fieldwork in Oaxaca, many a written pernicious petition has been found in Santa Muerte shrines below ebony candles that wish alcoholism, drug addiction and eventually death to foes. Nevertheless, the skeleton saint is also turned to for protection from death. More recently, we have observed prayer cards circulating which solicit Santa Muerte in her role as Santa Sanadora, that is to say as a salubrious saint, to safeguard devotees from covid-19.

Devotees, such as Yuri Mendez, a self-identified Santa Muerte witch, pray to the saint in public chapels or at their home altar, imploring their effigy to keep them and their families safe. The white Santa Muerte votive and statue have been the most favoured for keeping covid-19 at bay. Yuri also recommends to devotees the purple healing candle, along with offerings of an eggplant due to its mauve colour and a glass of olive oil. In Santa Muerte devotion, colour symbology is vital and white is the colour employed for cleansing, blessing and purification of homes whilst purple connotes healing.

However, other votives are also being lit, such as the seven-coloured candle typically used for multiple miracles, and the black candle which may also be used for protection, not just hexing and death. Also a new candle recently became available specifically for healing of coronavirus featuring a prayer and the image of Santa Muerte. Libations of tequila, mezcal, and other types of liquor together with other offerings such as tobacco, victuals and flowers are always proffered to the saint in a quid pro quo with death for life. Much as ancient Greeks offered garlic to the witch goddess Hecate, we have noted that devotees of death sometimes offer Santa Muerte the pungent bulb, especially when asking for health and healing.

Bare Life

The Mexican government has been berated for its ineffectual attitude towards coronavirus but if truth be told in the post-colony transience is tragically the norm. Giorgio Agamben has written about “bare life” using the Greek word zoe to describe a situation whereby human life is unprotected and is constantly exposed to death. This, he explains, takes place in a State where the indiscernibility of law contributes to a normative crisis where humans are treated no better than animals and can be subjected to violence and killed with impunity. As Mexican peace scholar Pietro Ameglio Patelli has pointed out, in Mexico every citizen has been reduced to bare life to“zoe: that is unprotected life, … of a being that can be subjected to violence, kidnapped, ill-treated or humiliated and murdered with impunity.

The Mexican murder rate in 2019 reached an all time high, with 35,000 confirmed murders. Furthermore, as a result of the drug war 65,000 people have vanished since 2006, confirming that the president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador`s policy towards narcos, summarized in his maxim “abrazos no balazos” (hugs not bullets), has been ineffectual. Femicide and gendered violence in Mexico is a dire problem. Perpetrators have been treated with impunity. The country has been named one of the most dangerous countries for women. According to a Mexican NGO, every 18 seconds in Mexico a woman is raped 40 and government figures note an average of 10 women are murdered daily 41.

The number of femicides has grown 137 percent over the past five years. Mexican authorities have hazy definitions of femicide which allow it to be treated with laxity. The Femicide Observatory, a coalition of 43 groups that document crimes affecting women, found that a mere 16 percent of female homicides in 2012 and 2013 were classified as femicides and only 1.6 percent resulted in convictions. Coronavirus now adds itself to the long list of threats to life in the Mexican post-colony. When we asked Zaniyah, a devotee of death, why she worshiped Santa Muerte, she told us ‘porque lo unico seguro es la muerte’, because the only thing that is sure is death.

We have often wondered whether devotees of death are less afraid of death than we are, after all they are constantly asking the skeleton saint to give them and their loved ones one more day. For example, Josefina told us her son had been sick for a long time and doctors had been unable to help him, therefore she had turned to saint death. She had bought a statue and established a shrine in her home. Every day, she told, she prayed to the effigy and every week offered her saint a cigarette, placing it in her ear and she told us that the saint puffed heavily enjoying every single toke. When her son made a miraculous recovery, she knew, she stated, that la Santa had heard her prayers.

Doctor Death

In asking Saint Death to vanquish their ailments, devotees not only have specific prayers at their disposal but also a number of rituals. La Biblia de la Santa Muerte, for example, contains five such ritual recipes for recovering both one’s own health and that of loved ones. The ‘first ritual for health’ is representative of the genre:

1 medium stalk of rue

1 meter of purple ribbon

1 votive candle for health (purple)

1 bottle of Santa Muerte lotion

1 cigar

1 maguey leaf

1 black pen

Procedure:

With the black pen write down all your ailments on the ribbon and then use the ribbon to tie up the rue in a bunch. Apply a bit of the Santa Muerte lotion to the bunch of rue. Light the cigar and blow smoke over the rue.

Next, cleanse your entire body with the rue, starting with your head and working down to your feet, making sure you pass the rue several times over the part of your body that’s most ailing. As soon as you finish, wrap the rue in newspaper and throw it away.

Take the sharp tip of the maguey leaf and write your full name along the width of the candle. Now cleanse your whole body with the candle, starting with your head and ending with your feet, again making sure to pass over the most affected body part several times. Light your candle and recite the prayer printed on it. It should burn in front of your Santa Muerte or place it on your altar, but always ask her to take care of your health.

This ritual would seem very familiar to many Santa Muertistas, since, with the exception of the Santa Muerte lotion, both the ingredients and the act itself come directly from Mexican folk healing practices, or curanderismo. The latter syncretically draws on Spanish, Indigenous, and, to a lesser extent, African healing practices to offer ailing Mexicans a cheaper and more holistic alternative to Western medicine. Rue is a plant that was brought by the Iberians to the New World, where it continues to serve the same purpose that it did in Spain and Portugal, and even in ancient Greece.

Ethnohealing with Death

Rue was used in ancient Greece and is used in modern Mexico and much of Latin America to protect against witchcraft and the evil eye, which continues to be a widespread belief among the working classes of Ibero-America. In ethnohealing practices, many Mexicans also brew the bitter herb into a medicinal tea that is thought to cure a wide range of maladies including the same headaches, dizziness, stiff neck, and inner ear problems that have been plaguing at least one of us. Here in the Saint Death health ritual, rue serves as a kind of cleansing sponge that absorbs sickness as it’s passed over the body of the afflicted. After the cleansing ritual, the contaminated rue is tossed in the garbage, where it won’t be a potential contagion.

Two other ritual ingredients serve to enhance the cleansing power of the rue. Since purple is the primary colour of healing, the ribbon of this hue, which is tied around the rue, reinforces the herb’s curing power. Of all the ritual ingredients, the cigar has the most powerful link to healing, despite being a carcinogen. Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas smoked, chewed, and drank tobacco tea for inter-related medicinal and spiritual purposes.

Today the use of cigars and cigarettes in both folk healing practices and African-diasporan religions is ubiquitous . The use of tobacco dates back to pre-Hispanic times in Meso-America where shamans have long employed it in rites of healing. We ourselves have had tobacco smoke blown over our bodies on numerous occasions, in Ecuador by a Quechua-speaking shaman and multiple times by Santa Muerte leaders and shamans across Mexico. Statues of the skeleton saint are also often ‘awakened’ and ‘blessed’ by devotees by suffusing them in cigar and cigarette smoke, as Kingsbury relates here. As described earlier, in the case of Josefina, cigarettes may be placed in or on statues as offerings. For most practitioners of the Saint Death health ritual, tobacco serves as a powerful agent and symbol of healing.

Like tobacco, maguey, also known as the century plant, links Mexican Santa Muertistas to their pre-Columbian past. The Aztecs used the plant for various maladies, such as topical wounds and gout. Moreover, the Aztecs and other Indigenous groups in central Mexico brewed the juice of the plant into a fermented drink called pulque, which contains substantial quantities of vitamin B and still serves as an important source of nutrition for a significant but diminishing number of impoverished campesinos in rural central Mexico.

Seeking stronger drink than pulque, Spanish colonists distilled the juices of the maguey and blue agave plant into mezcal and tequila, respectively. Of course in the Santa Muerte healing ritual, the leaf of the plant serves as a writing instrument, not as a medicinal salve. Thus the multi-purpose maguey functions as an essential ingredient in this recipe for healing by lending its curative fibers to make an inscription on the votive candle. Like the rue, the purple votive candle also serves as a cleansing agent, absorbing affliction as it traces the body of the petitioner. The contagions collected in the purple candle are then symbolically incinerated as the wax is left to burn at the altar of Doctor Death.

Death the Healer

Santa Muerte’s role as faith healer has often been ignored by the mass media who focus on her as a narcosaint but in Mexico, across Latin America and even in the USA, devotees regularly turn to her for health and healing. Presently they are lighting white candles as they petition her to keep them and their loved ones safe from Coronavirus, as well as the many other evils that threaten their safety.

More importantly, however, unlike most of us in the Western world who have difficulty accepting death, veneration of Santa Muerte allows those who worship her to be ever ready and ever willing to meet her hollow gaze and take her bony hand when the time comes for them to leave this world. The new religious movement is based, much as Indigenous faith once was, upon acceptance of the duality and interdependence of life and death. For believers in Santa Muerte this duality is the only certainty and furnishes the framework for understanding their reality. I, Dr. Kingsbury, realised this one day when I asked a devotee of death whilst visiting their house in rural Oaxaca, whether I could use their internet to send a quick email. The Wifi network was easy enough to find, it was called Santa Muerte. I asked for the password. Abby, the devotee, replied to me ‘vida y muerte‘, life and death.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford and is author of the forthcoming “Daughters of Death: The Female Followers of Santa Muerte” with Oxford University Press. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda. Follow Dr. Kingsbury on Twitter