Co-authored by Dr. Kate Kingsbury* and Dr. Andrew Chesnut

In this piece we explore the portrayal of Santa Muerte, the Mexican Female Folk Saint of Death in ‘Penny Dreadful: City of Angels.’ The show is set in 1938 Los Angeles which, it claims, is ‘a time and place deeply infused with Mexican-American folklore and social tension.’ The television series in actual fact demonstrates creator John Logan’s ignorance of Mexican culture and his penchant for cultural misappropriation in his misuse of and fictional fabrications around the folk saint of death.

Over the past decade, Mexican folk saint Santa Muerte has become a leading lady in Hollywood starring in such films and TV series as Breaking Bad, Bad Boys for Life, True Detective, Not Forgotten, and now the new season of Penny Dreadful, “City of Angels.” While Santa Muerte and her evil sister Magda will be protagonists throughout the eight episodes, here we will only review the premier entitled “Santa Muerte.” Set in Los Angeles of 1938 the first episode introduces us to supernatural sisters Santa Muerte and Magda who determine the fate of mid-20th century Angelenos and their sunny city.

The supernatural sorority, of course, is a fiction imagined by creator John Logan. In real life devotion to the object of the fastest growing new religious movement in the West has no sister or any family members for that matter. It centers solely around one figure, Santa Muerte, who takes on different powers according to the colour of her garb. Despite the title of the premier, it’s the dark sibling Magda who steals the show. Dressed to kill, literally, in Nazi-style BDSM black leather the Succubus-like sister named after the apocryphal prostitute Mary Magdalene sews discord and destruction in the City of Angels, mostly by fomenting a race war between Mexican-Americans and Anglo-Americans.

In the episode that would have been more appropriately titled “Magda” the demonic shape-shifter first appears as a sexy German immigrant to a Nazi compatriot from Essen, a physician who is leading the local campaign to keep the US out of WWII. Later on she materializes in the guise of an advisor to a racist White city council member whose anti-Mexican policies attract the attention of the local Nazi spy network. In media interviews, Logan has been evasive as to why he chose to give Saint Death an evil twin but we surmise that Magda was invented as the dark alter-ego, the yin to Santa Muerte’s yang.

In some forms of devotion there are three manifestations of Santa Muerte – the Lady in Red for matters of the heart, Lady in Black for protection and harm to others, and Lady in White for gratitude, purity, and all other matters. Ironically, in the late 1930s and until the 1980s anthropologists in Mexico reported Santa Muerte being petitioned, predominantly by women, for only one reason – love magic of the Lady in Red, the one manifestation completely absent from the first episode.

Like Maria Vega, the matriarchal devotee in Penny Dreadful who tells us the Skeleton Saint is good and takes people to heaven, most believers see her as a benevolent saint generously granting miracles of health, wealth, and love. By creating Magda, Logan was able to integrate Santa Muerte’s notorious dark side without actually ascribing it to her. In so doing, the critically acclaimed British series could avoid charges of cultural and religious insensitivity in its depiction of the fastest growing NRM in the Americas. Yet as we will point out through the insensitive and erroneous portrayal of the folk saint, Logan has certainly culturally misappropriated Santa Muerte to support his story-line. This is glaringly obvious not least when Tiago, the Chicano police officer, explains to his White partner when they discover several corpses with Day of the Dead face paint, that ‘Day of the Dead make up honours Santa Muerte’. This of course is completely wrong. It is hard to tell whether Logan intentionally or ignorantly muddles his facts up. Either way, considering the wide viewing audience, dissemination of such misinformation means many may take such fictional fabrications for truth, perpetuating misunderstandings of Santa Muerte.

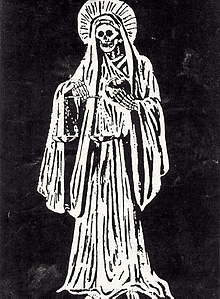

Overshadowed in the opener by her sinister sister, Santa Muerte appears as the White Girl (la Nina Blanca, which is one of her main monikers) in attire that evokes a Spanish gothic advocation of the Virgin Mary. Her piercing green eyes and light complexion add to her European look. In all fairness back in the 1930s and throughout most of the 20th century Santa Muerte’s iconography drew from Spanish Gothic imagery. She was depicted with a nun’s habit, holding the hourglass of life in one hand and the scales of justice in the other.

However, the Skeleton Saint developed on Mexican soil. In her depiction on the TV show the only nod to her Mexican identity are the inlaid skulls on her regal tiara, and of course even skulls comprise ubiquitous symbology of death. Logan has therefore stripped the folk saint of her Mexican origins in a way that evokes the dark past of the conquest of the Americas. Much as those who settled in the New World saw it as a tabula rasa upon which to build their financial success, it seems Logan has appropriated Santa Muerte to forge his Hollywood fiction and glean the financial benefits of a prime-time show and there are certainly no records of the folk saint being worshipped in 1930s Los Angeles.

Another glaring omission is that the saint of death does not appear in the show in skeletal form, rather Santa Muerte is played by two fleshy, young women. Lorenza Izzo, the Chilean actress plays the white garbed version of the folk saint- in the only nod to Santa Muerte’s Latin origins, although it’s the wrong country- and Natalie Dormer as Magda. By depicting Santa Muerte as an incarnate human figure, Logan has once again demonstrated his complete ignorance of his subject matter and of Mexican culture. Santa Muerte should never be portrayed with flesh on her bones. She is known by Mexicans as la Huesuda, which means the Bony Lady, and this for a reason: in at least 99% of her iconography, both past and present, she is always represented as a fleshless skeleton.

Logan and his crew thus display total ignorance of the Saint’s origins. In part she hails from La Parca, the female Grim Reaper brought by the Spanish to the New World. La Parca literally means the parched one, and alludes to the reaper’s desiccated disposition which Santa Muerte has inherited in her Mexican guise. In fact, in Mexican lore the Folk Saint is said to suffer so severely from dehydration due to her cadaverous composition that devotees offer their Santa Muerte effigy daily oblations of water to quench her supposed insuperable thirst.

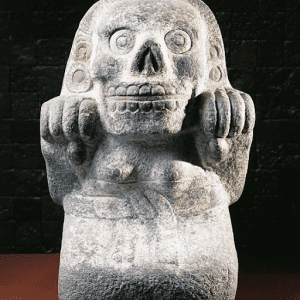

As a syncretic saint, Santa Muerte also derives from Mexican death deities. After all, the Spanish never worshipped La Parca, but Indigenous peoples of pre-Hispanic Mexico petitioned death goddesses and gods, thus when they encountered the Spanish Grim Reapress they most likely perceived her as akin to their thanatological divinities and began to worship her. Most death deities hailing from pre-Columbian times were also depicted with skeletal attributes such as Yum Cimil, the Mayan death god who has a skeletal rib cage, a skull head and extruding bowels to signify flatulence in the moment of death. Whilst, Mictecacihuatl, whom many Santa Muerte devotees have claimed is the Skeleton Saint’s supernatural ancestress, was portrayed with flayed skin, a skull head and a chasmal, skeletal jaw much like Saint Death is today. Logan has entirely obliterated this aspect of Santa Muerte and thus her Indigenous past. For a show that claims to highlight racism, misappropriation of la Muerte makes one wonder.

For Logan and his producing partner, Michael Aguilar, Magda depicts Santa Muerte as a so-called ‘chaos demon’. Such attributions again reek of cultural misappropriation, misunderstanding and neocolonialism. Santa Muerte is not in any way linked to the devil. To assume so is to suffer from a colonial hangover. When the Spanish colonialists came upon the death deities of pre-Hispanic Mexico, they misconstrued them not as Gods and Goddesses but as satanic figures and forced Indigenous people to abandon their worship at risk of torture, seeking to obliterate all local religious forms and replace them with Catholicism. Missionary accounts penned during the era describe local gods and goddesses as ‘devils’ sowing discord, just as Logan and Aguilar have turned the dark side of Santa Muerte, Magda, into a chaos demon, without understanding the Saint’s role in Mexican religion.

In both her personas in the show, whether as psychopomp receiving the bodies of the deceased or as Magda, whose only goal is to reap havoc and discord, Santa Muerte only has one true purpose: death. This entirely overlooks the Bony Lady’s appeal to Mexicans which harkens to her Indigenous past underscoring the interdependence of life and death, the continuity, and cyclical nature of the cosmos. Many Mexicans see Santa Muerte not as an agent of death, but as a caring supernatural mother who brings new life in all ways to their lives, whether through health and healing, financial success or blessing new ventures. Many women even ask the saint of death to bring life to their barren wombs. Holding the scales of justice in many depictions, the Female Folk Saint is also well known in Mexican lore for interceding for devotees when they face unfairness and bringing about equity. Yet Logan’s saint is monomorphic.

In the anachronistic altar scene, which features three-dimensional depictions of the saint that did not exist in the 1930s, Maria Vega asks Santa Muerte for aid. Logan’s fictional saint refuses and tells the devotee that her only duty is to receive the bodies of the dead, for Santa Muerteros this could not be further from the truth. Santa Muerte’s appeal and the mushrooming of the movement is precisely due to her ability to grant devotees miracles of all kinds with all manner of problems, as in the the best-selling rainbow-colored Seven Powers candle that Santa Muerteros light to ask her to bless them and their endeavours in all the many ways possible. The real folk saint is a complex, multifaceted miracle worker with a rich history and a sophisticated presence in the present. Logan’s simplistic saint is but a sorry travesty.

*Dr. Kate Kingsbury obtained her doctorate in anthropology at the University of Oxford and is author of the forthcoming “Daughters of Death: The Female Followers of Santa Muerte” with Oxford University Press. She is a polymath interested in exploring the intersections between anthropology, religious studies, philosophy, sociology and critical theory. Dr. Kingsbury is Adjunct Professor at the University of Alberta, Canada. She is fascinated by religious phenomena, not only in terms of their continuity across the Holocene and into the Anthropocene but equally interested in the changes wrought to praxis and belief by humans ensuring the infinite esemplasticity that is inherent to all religions, allowing for their inception, survival, alteration, regeneration and expansion across time and space. Dr. Kingsbury is a staunch believer in equal rights and the power of education to ameliorate global disparities. She also works pro bono for a non profit organisation that aims to empower and educate girls in Uganda. Follow Dr. Kingsbury on Twitter