“Liturgical Sense” is a new series on this blog and will feature weekly installments. The goal of Liturgical Sense is to examine various bits and pieces of the liturgy in order to understand them both individually and within the whole liturgical structure. Borrowing the title from Louis Weil’s book, the goal is to look at the “logic” of the liturgy, or as Fr. Alexander Schmemann put it, “the liturgical coefficient.” Future posts will include the Prayers of the People, the Collects, the Gloria, the sermon, the anaphora, and much more.

Introduction

Liturgy has an inherent flow, an inner logic that guides participants from one element to the next in praise and worship of the triune God. The structure, and therefore logic, of the liturgy is know as the ordo, and within the world of liturgy there are varying ordos. The study of historic ordos and their development is known as liturgiology. The process of explicating and elucidating said worship is known as liturgical theology. Liturgical theology is the focus of Liturgical Sense

Fr. Schmemann described the “liturgical coefficient” in the opening to his book Introduction to Liturgical Theology. The belief is that each component of the ordo may have inherent meaning but truly finds significance and definition based on its location in the liturgy and therefore its relationship with every other element. For example, some Eucharistic prayers contain the Lord’s Prayer immediately before the Fraction (Breaking of the Bread) whereas others place the Lord’s Prayer at the beginning of the liturgy. The Lord’s Prayer is still the Lord’s Prayer but it means something slightly different in each of these locations. Likewise, in Lent and other penitential services, the corporate Confession of sin takes place in the opening moments of worship while during the rest of the year it usually falls after the Prayers of the People and before the Peace.

Fr. Schmemann offered a working definition of the “liturgical coefficient”:

“Worship simply cannot be equated either with texts or with forms of worship. It is a whole, within which everything, the words of prayer, lections, chanting, ceremonies, the relationship of all these things in a ‘sequence’ or ‘order’ and, finally, what can be defined as the ‘liturgical coefficient’ of each of these elements (i.e. that significance which, apart from its own immediate content, each acquires as a result of its place in the general sequence or order of worship).[1]

You can already see from Fr. Schmemann’s quote some specific liturgical components that I will cover in our series. What is the liturgical meaning of the lectionary? How can a sermon be liturgical? Moving beyond the quote, part of our liturgical worship is the time that we inhabit and transcend on the Lord’s Day. Mary’s Magnificat is refreshed and seen anew when said or chanted on the Feast of the Annunciation or juxtaposed with the national celebration of Mother’s Day. The church calendar—and therefore the world’s calendar—is woven into worship as well.

Our corporate quest in Liturgical Sense to examine and study the individual elements of the liturgy will look to this principle as our North Star. To understand the one is to make sense of the whole. My desired outcome is a deeper understanding of liturgical worship and a renewed desire for liturgy that is robustly theological.

Relationship Rethought

There is an ongoing liturgical disagreement between two different camps and I’d like to briefly mention it here in order to offer a synthetic third perspective. Michael Aune has outlined these two camps as his own and the other as the Schmemann-Kavanagh-Fagerberg-Lathrop school.[2] The disagreement is about deciding who or what is active in the liturgy. Is God active in the liturgy or is the church? Aune argues for a top-down approach in which God is the active agent in worship. The school of thought represented by Schmemann, according to Aune, argues for a bottom-up approach focusing on the activity of the church.[3]

I think that this is an unnecessary and false dichotomy. Rather than either/or we should be speaking the language of both/and. All liturgical worship is call and response. God is the First Mover in worship. He calls out to His people and His Church responds to this call by gathering together, praying, hearing His word, and breaking bread. It is not that God is the only active agent in liturgical worship but that He is the object, subject, cause and catalyst of our worship and adoration.

The Church’s activity is secondary in the sense that the Church does not initiate anything apart from the Holy Spirit, however the Church’s activity is essential to both liturgical worship and liturgical theology. This is the “synthetic third perspective” mentioned above. By combining the top-down and bottom-up approaches we are given the picture of the Church in worship and God inhabiting the praises of His people. Everyone is active, everyone is participating, and God is still primary.

First Things: The Gathering

Let us use the act of gathering together on Sunday morning for our first case study in Liturgical Sense. There can be no worship or liturgical experience without the people of God first assembling. Being the week before Pentecost, I’m particularly reminded of Acts 2:1, “When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place.” It may seem too obvious to mention, but for Jesus to be present among two or three they first need to be gathered together in his name.

This gathering is called synaxis and it is always a response to God.

I believe that the liturgy actually begins early on Sunday morning when the decision is made to join the gathered faithful for song and praise. The Holy Spirit prompted, nodded, nudged or reminded you to be with Christ’s body and you responded in obedience. You could have been in a million different places while others were at church, yet you were exactly where you were meant to be: with the church.

While many missional arguments can be made about where and when a church should meet, the witness of the early church should guide us. The earliest Christians, according to Justin Martyr, gathered together on the Lord’s Day (Sunday) for worship. Likewise, after the conversion of Constantine the church began to meet in basilicas and other public settings that had been set aside and consecrated for holy use. Where and when the church gathers is an important detail because it speaks to what one believes to be taking place.

The gathering of God’s people for His worship is important because it undergirds everything that takes place in the liturgy. True Sunday worship cannot be done alone. The pilgrim people of God assemble as the Church, Christ’s bodily representation on Earth for the celebration of the Lord’s Day and for the sharing of the Eucharist. In the celebration of the Eucharist the Church becomes “that which she already is” and we get a glimpse, a foretaste of the Kingdom. We corporately share in the practices of kingdom citizens through the confession of sins, prayer, the offering of the peace, and our own sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving.

As the people come together they bring with them the totality of their being: their homes, jobs, relationships, finances, talents, desires, fears, sins, and hopes. Without fully realizing it, parishioners bring their world to the altar that the Lord may accept their offering and then commission them back into the world as agents of radical transformation and redemption. Fr. Kavanagh wrote that, “Liturgy is doing the world the way it was meant to be done” and therefore the church does not gather to “do church.”[4] We are sent back out into the world for the life of the world. We cannot be sent unless we are first gathered, taught and fed!

Next week we will examine the use of the word “Amen” by the Church in worship.

Helpful Resources

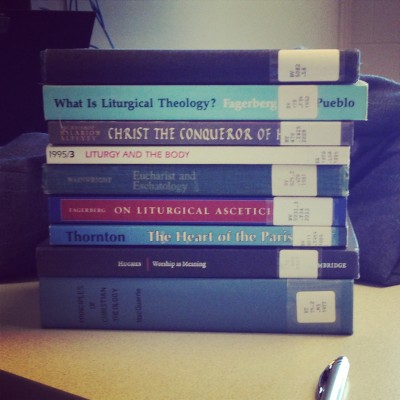

For some of you this may be the first time you’ve delved into liturgical theology or really studied individual elements of the ordo. Here are some names with which you should become acquainted (the hyperlinks will direct you to their Amazon.com page). Enjoy!

For those interested in studying Anglican liturgies: The Book of Common Prayer

[1] Schmemann, Introduction to Liturgical Theology, 19.

[2] This is captured well in the opening pages of Maxwell Johnson’s book, Praying and Believing in Early Christianity.

[3] I think that Aune mischaracterizes the work of the Schmemann-Kavanagh-Fagerberg-Lathrop school.

[4] A combination of quotes from Kavanagh, Fagerberg and Schmemann. Kavanagh from On Liturgical Theology; Fagerberg from What Is Liturgical Theology?; Schmemann from The Eucharist.