As we approach Reformation Day within the Protestant corners of the one holy catholic and apostolic church there is a tendency to romanticize the true nature of the various reformations to the point that the baby is all but thrown out with the bathwater. As an Anglican, and as one who believes in the branch theory of the church, to misread history in this manner is not only negligent: it is also lazy. My goal is to briefly outline the lasting and true legacy of the English Reformation in the remainder of this post.

My friend and former mentor, Bishop Fitzsimmons Allison, once said to me, “Anyone who believes the English Reformation was about King Henry VIII truly deserves King Henry.” Though we may not agree on imputation or the new perspective on Paul, I have to agree with Bishop Allison wholeheartedly on this point. To resign the English Reformation to King Henry’s need for a divorce or control over his church is to miss the point entirely. The English Reformation wasn’t the byproduct of a judicial or ecclesiastical statement on the King’s marriage, rather it was the culmination, fulfillment, and realization of a spirituality that far preceded the Tudor dynasty, dating back to the second and third centuries after Christ.

A reformation was already afoot in the fourteenth century as John Wycliffe began translating the Bible into the English language. An influencer of Jan Huss, William Tyndale, and Martin Luther, Wycliffe set in motion the movement toward giving the English people a Bible in her own tongue. Translating the Bible out of Latin is seen as a benchmark of the various sixteenth century reformations but too often it is forgotten that an Englishman had started the trend over 150 years earlier. Wycliffe died some 150 years before Thomas Cranmer became Archbishop, but he is still remembered as the “Morning Star of the Reformation.” Continuing his great work, Tyndale and Coverdale also translated portions of the Bible into English ultimately climaxing decades later with the production of the King James Version in 1611; thus setting the biblical standard for centuries.

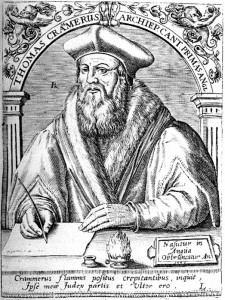

Similarly, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer worked his liturgical genius during the 1540’s and early 1550’s under Kings Henry and Edward to reform English liturgy. Cranmer was responsible for the first piece of liturgy written in English (the Great Litany of 1544), much of the Book of Homilies, the inclusion of the Great Bible in parishes around the nation, and the 1549 and 1552 Books of Common Prayer. These landmarks insured one thing: a common language for the faith and worship of the Church in England. Every parish in the country would now read the same Bible, hear the same homily, and pray the same prayers in the exact same language.

The 1549 Prayer Book was a compilation of various ancient sources from the early church and post-Council period. Elsewhere I have written:

The 1549 book was adapted from many sources in use at the time. The Sarum Rite as used in the Diocese of Salisbury was perhaps the most important component. Other primary sources for Cranmer’s liturgical compilation include: Quinones’ Breviary, the Archbishop of Cologne’s Church Agenda, the Pie, and Bucer’s Ordination Service (for the 1550 Ordinal) amongst others. Cranmer’s work should be labeled as both reform and return because he introduced new elements—chiefly his original collects—and yet he also returned to ancient practices and prayers. Bard Thompson suggests four vital reasons for the introduction of the 1549 book: exposing people to the whole of Scripture, using English to reach the “hartes”, simplifying the service, and creating uniformity within England. Duffy stresses the significant change for English Christianity and spirituality in the 1549 book, perhaps resulting in spiritual “impoverishment.”[1]

Additionally, Cranmer relied heavily upon the Gelasian Sacramentary as part of his liturgical revival and reform which can only really be described as a return to the words and forms of ancient liturgical worship. By the time the second prayer book was produced in 1552, England was worshipping liturgically together on a weekly basis reminiscent of the Didache and Justin Martyr’s Apology. The English Reformation was not without its dark moments.

One of the saddest events was the “stripping of the altars” and the destruction of the monastic tradition during the reign and at the order of King Henry. A wealth of liturgical, ecclesiastical, monastic, and artistic brilliance was lost and as a result many pockets of evangelical Anglicanism are didactically rational rather than being beautifully holistic.

Bishop Lancelot Andrewes said it best when describing the hooks upon which the Church of England can hang her theological hat: “One canon reduced to writing by God himself, two testaments, three creeds, four general councils, five centuries and the series of fathers in that period – the three centuries, that is, before Constantine, and two after, determine the boundary of our faith.”[2] To be Anglican, therefore, is to celebrate the rich and vast history of liturgy and theology (one might say liturgical theology) of Christ’s Church over the last two millennia; it is to be rooted in the Great Tradition of the Church and firmly committed to ecumenical efforts; it is to embrace the heritage of Christian thought and spirituality stemming from missionary efforts, monastic soil, and an unwavering desire to read and pray in one’s own language.

What then is the true legacy of the English Reformation? A common Bible and a common prayer book in a common language for a common people.

[1] From “The Edwardian Prayer Books: A Study in Liturgical Theology” as posted on Academia.edu

[2] http://datsociety.blogspot.com/2012/09/11-lancelot-andrewes-1555-1626-private.html