This is a post contributed by my friend, Matthew Dallman. Matthew is the Executive Director of Akenside Press and his bio can be found below.

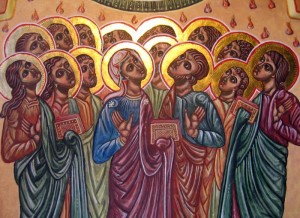

Many of us have our favorite moments in Holy Scripture for personal reflection. Among mine are the Annunciation to Blessed Mary, the Parable of the Leaven, the Binding of Isaac, Jesus’ Agony in the Garden, and Eve’s confrontation with the Serpent in Eden. Yet the one I think about the most is the second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles—that is, Saint Luke’s account of the Day of Pentecost.

Liturgically, of course, Pentecost is a treasure. For many people, the hymns, “Come, Holy Ghost” and “Come down, O Love divine” trigger glorious memories of life in the Church. There are traditions abundant in parishes and cathedrals around the world.

Yet in all such richness, I confess that the aspect of Acts 2 that shows up on the Solemnity of Pentecost—that is, verses 1-11 as the first of the three appointed lessons—is not the part of the chapter that thrills my imagination the most. I would never discount its importance, for it describes a great Mystery of the faith! Yet the chapter as a whole points toward nothing less than what my favorite theologian, Anglican priest Martin Thornton, called “a staggering spiritual experience, the implications of which took centuries to formulate.”[1]

Think of it all. Yes, the “tongues as of fire,” yet also Saint Peter’s sublime preaching. The confidence in his voice—“Men of Judea and all who dwell in Jerusalem, let this be known to you, and give ear to my words.” The humor—“These men are not drunk, as you suppose, since it is only the third hour of the day.” Then one arresting image after another, first quoting the prophet Joel—“Spirit poured upon all flesh,” “blood, and fire, and vapor of smoke: the sun shall be turned into darkness and the moon into blood.” Then quoting King David—“thou hast made known to me the ways of life.” Then comes the announcement of miracle of miracles—“God raised [Jesus] up, loosed the pangs of death,” and “This Jesus God raised up, and of that we all are witnesses.” Yes we are!

The people hearing all this asked basic yet crucial questions. “What does this mean?” (v. 12) and “Brethren, what shall we do?” (v. 37) are exemplary given the outrageous atmosphere of energy, vibrancy, and—ok, I will say it—cosmic disclosure. The first Christians encourage us to explore with our priest, pastor, or spiritual advisor the very same questions—such is the heart of genuine spiritual direction seen as guidance in prayer.

Responding, Peter exhorts the people to repentance and baptism, both for the forgiveness of sins, and for receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit. These are counter-cultural words—“save yourselves from this crooked generation”—and they are effective words, for “about three thousand souls” were baptized.

For some, the story may climax here, but yet in the very next moment, v. 42, is something subtle yet fundamental: “And they devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers.” Despite its plainness, the significance of this sentence cannot be overstated. The verse itself may not inspire in us the holy fear of God, but it provides crucial, practical direction to those people who have been “cut to the heart” (v. 37)[2] by the presence of the Holy Spirit and now need to know, in no uncertain terms, what shall we do?

Whether its emergence was in fact sheer spontaneity as Saint Luke implies, we see here what is the fundamental framework of the Christian life. This framework is threefold: 1. apostles’ teaching and fellowship, 2. the breaking of bread, and 3. the prayers. Each is a distinct kind of action yet also intimately related to, and requiring, the others. The New Testament Church was built upon all three, lived out corporately and in dynamic interaction.

Ever wonder how this framework might have come to be? Perhaps creative meditation would help: we can suspect the apostles likely gave immediate teaching on the need to perpetuate Jesus’ Last Supper through the Eucharist. What’s more, we already have those two paradigmatic questions (vv. 12 and 37) which doubtlessly the people continued to explore with the apostles in community. And of course the inhabitants of Judea and Jerusalem were well versed in daily prayer patterns, and yet in the brand-new Christian environment, is it too much of a stretch to suppose the apostles also taught the people how to pray, based on how Jesus taught them—that is, the Our Father? The earliest liturgical evidence we have, the Didache, dating from at least the late first century, clear instructs (in ch. 8) to pray “as the Lord commanded in His Gospel. . . . Pray this three times each day.” The apostles, we may suppose, taught the Our Father as the model for all set-prayer.

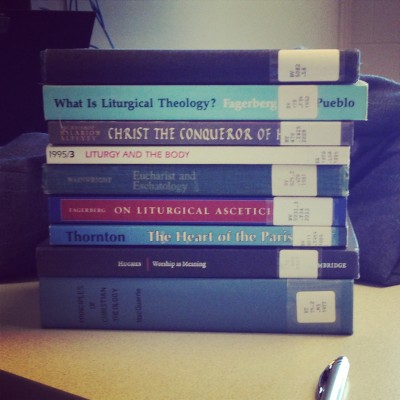

Decades and centuries of Christian life ensued, in stunningly diverse ways and practices. And yet by the time of Saint Benedict and his Rule, the implications of Acts 2:42 become streamlined into a practical pattern. Apostles’ teaching and fellowship becomes what we today call “Devotion”—that is, a combination according to personality and context of sacred reading, Christian service within the community and beyond, catechesis, contemplation, fasting, and more. The breaking of bread becomes, of course, the “Mass” or “Eucharist,” the central activity of the gathered community. The prayers become the “Divine Office”—the Our Father pattern expanded by means of the Creed with psalms, canticles and Scripture.

Tradition continued to ebb and flow as the living Body of Christ, and practice varied widely in the Church both East and West.[3] And yet, the purpose of this threefold framework remained firmly revealed in Acts 2 as the comprehensive way the People of God pray. It is the basis for our obedience to God’s action, His presence, His disclosure. This threefold framework—which Martin Thornton proposed we call the threefold “Regula,” which simply means Rule, Pattern, Model—is in fact the means of our repentance, for it is precisely how we turn to God, day-to-day, week-to-week. As the model of prayer it is also the basic weapon against sin.

Anglican tradition presupposes the centrality of the threefold Regula. The Book of Common Prayer orders the corporate life of sacraments centered on Eucharist in the Mass, it provides comprehensive forms for the daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer (and, in more recent revisions, forms for Noon-day and Compline), and provides a catechism for use in Devotion, evidence that it assumes the need for the baptized to work-out within local, parochial context the implications of Christ for prayer, mission, and ministry. Hence the Book of Common Prayer, for all its interactions with the volatility of the 16th century, is also the spiritual heir of the Rule of Saint Benedict, for both communal documents consolidated the insights of their age into a practical and enduring order or Regula for active and conscious participation in the redemptive organism, the Church.

There is an additional aspect to consider. It became axiomatic among late twentieth-century liturgical theologians (Kavanagh, Lathrop, Weil, among others) to refer to the Eucharist as “the repeatable part of Baptism.” Yes, but that is incomplete. In fact, the threefold Regula is the repeatable part of Baptism. Each aspect requires Baptism, and each aspect in its own way lives out the baptismal reality of ontological incorporation into Christ’s Body. Only by being members of Him can we pray to Our Father through the Divine Office, feed on Him in the Eucharist, and be His Hands and Feet and Eyes to manifest in Devotion His compassion and blessing upon the world. The dimensions of Regula, then, enact existentially what we promise in Baptism: to believe in the triune God, to resist evil, to repent, to proclaim the Gospel, to seek and serve Christ in all persons, to strive for justice, peace, and human dignity. And, note, the 1979 Book of Common Prayer makes Acts 2:42, and hence the threefold Regula, itself one of the baptismal promises.[4] Regula can never be anything less than central to mature discipleship.

The Grace of Pentecost, then, is consummated in the spontaneous joy of corporate life made possible through the threefold Regula—“praising God and having favor with all the people” (v. 47). Pentecost is a staggering spiritual experience, not only because of the “tongues as of fire,” but because revealed was a new way of total living. The threefold Regula, despite its deceptive simplicity, is the means by which we, the members of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church, embody, that is, “repeat,” our Baptism.

And let me conclude by saying that all of this is particularly pertinent to Anglicans. By regarding the threefold Regula in this scriptural and spiritual light, Anglicans can see more clearly just what the Book of Common Prayer actually is. We presuppose Regula so much so that we tend to forget about it. Hardly a mere collection of services at the whim of liturgical fashion—the Prayer Book, as Regula par excellence, is a fundamental vehicle for Christian pilgrimage toward nothing less than the Vision of God. Any initiatives toward liturgical revision within the Anglican Communion must begin, and affirm, this biblical, apostolic, and hence truly catholic understanding of our Prayer Book, as well as be guided by that truth to maintain fidelity to traditional Anglicanism as well as New Testament Christianity.

[1]. Martin Thornton, The Function of Theology (Seabury Press: New York, 1968), 32.

[2]. Cf. Luke 2:35 for a tremendous parallel between the first Christians and Blessed Mary.

[3]. See The Liturgy of the Hours in East and West by Robert Taft, S.J.

[4]. See p. 304.

Matthew Dallman is married and the father of four girls. He is the Executive Director of Akenside Press. His first book is The Benedictine Parish: A Model to Thrive in a Secular Era. He has written for The Living Church magazine. He is a trained musician who has composed for films and wedding ceremonies. He has studied poetry with Yusef Komunyakaa and Carter Revard, integral theory with Ken Wilber, music with W.A. Mathieu, philosophy with Dr Herman Stark, and theology with Fr Thomas Fraser. He received a B.A. in English Literature with a minor in Creative Writing from Washington University in St Louis. He was raised a Lutheran (ELCA) but did not find home until age 35, when he stepped in St Paul’s Parish, Riverside. Within months he began to pursue a Master of Arts in Liturgy at Chicago’s Catholic Theological Union then also a Master in Theological Studies in Anglican Studies (focusing on the work of Martin Thornton), from Wisconsin’s Nashotah House Theological Seminary, and he began to discern a vocation to the Priesthood in the Episcopal Church.

Photo Credit: Advent Lutheran Church, Olathe, KS. Attributed to William de Brailes, who worked in Oxford, England, in the middle of the 13th century.