Perhaps few films in recent years have been the subjects of more anticipation than Robin Hardy’s THE WICKER TREE. The director (who helmed the cult horror classic THE WICKER MAN, now nearly four decades old) struggled for several years to obtain sufficient funding, and rejected several previous working titles (COWBOYS FOR CHRIST, THE MAY QUEEN and THE RIDING OF THE LADDIE) before settling on the one that conjured at least a ghost of the original. And though there are similarities, the title may well be the the source of the strongest resemblance to the 1973 film written by Anthony Shaffer.

Perhaps few films in recent years have been the subjects of more anticipation than Robin Hardy’s THE WICKER TREE. The director (who helmed the cult horror classic THE WICKER MAN, now nearly four decades old) struggled for several years to obtain sufficient funding, and rejected several previous working titles (COWBOYS FOR CHRIST, THE MAY QUEEN and THE RIDING OF THE LADDIE) before settling on the one that conjured at least a ghost of the original. And though there are similarities, the title may well be the the source of the strongest resemblance to the 1973 film written by Anthony Shaffer.

Also set in Scotland, THE WICKER TREE also features an ancient rite performed as an act of sacrifice, which victimizes an unsuspecting visitor. In 1973, it was police sergeant Neil Howie (the wonderful Edward Woodward), who is compelled to visit the tiny island of Summerisle to investigate a report of a missing child. Howie is provoked and finally kidnapped by the inhabitants of this rural enclave, whose pagan ways are an affront to his Christian beliefs. In 2012, the innocents are a couple of born again Texans, one a popular country/gospel singer (Beth, played by impressive newcomer Brittania Nicol), the other her bronco-riding boyfriend Steve (Henry Garrett). They’re also proponents of the “Silver Ring Thing,” tokens of their vow to remain pure until marriage. After a couple of well-received concerts in Edinburgh, the couple starts knocking on doors with tracts praising their Southern Baptist-style Christianity, but are rebuffed. Their hosts suggest they go further “into the country” to find more willing converts, so off they go to the village of Tessock.

Now, having seen the original film, in which a Christian is lured into dangerous circumstances in a pagan enclave, viewers may understand something similar will befall Steve and Beth, complete, perhaps, with attempted acts of seduction to test whether their virginity is an impermeable as their silver bands. The village tart, a childless, eccentric young woman named Lolly (the wonderful Honeysuckle Weeks) does set her sights on Steve, but the only villagers interested in Beth seem to be Lord Lachlan Morrison (Graham McTavish), a sort of stand-in for Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle, a wealthy patriarch who has ties to the local nuclear power plant. Lady Delia Morrison (Jacqueline Leonard) is his wife, a stand-in for Miss Rose the school teacher (though the two do not sing bawdy songs while drinking and lolling about on bearskin rugs, alas).

The nuclear plant is rumored to be the cause of an unexplained epidemic of infertility, which may or may not be connected to the notion that virginal outsiders Beth and Steve are “perfect” choices for the honored participants in the May Day festivities occurring the day after their arrival. The central May Day events, the “Riding of the Laddie” and the crowning of the May Queen, are apparently time-honored traditions in the village, and Beth and Steve are honored to be chosen to participate. And apparently the two chosen honorees need not be pure as the driven snow to play their roles, and Steve’s jaunt on a prize horse as part of a costumed “hunt” is only one way in which this “laddie” is ridden that day.

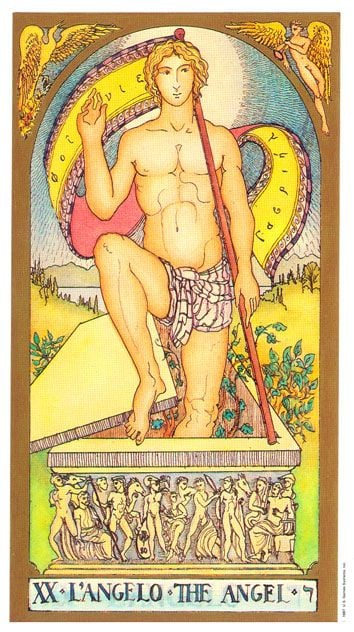

I’m not trying to give too much away, and honestly I would find it hard to do so, because many pieces of the puzzle in this thriller proved elusive to me. Anthony Shaffer’s screenplay for THE WICKER MAN showcased his talents as a mystery writer (he penned SLEUTH as well), but the script for THE WICKER TREE, written by director Robin Hardy, doesn’t deliver the same subtle layering and suspense, not to mention the oddity and black humor of the 1973 version. As much as I appreciated the attempt to create an alternate folklore and mythology for this village, connected via ancestry to Lord Summerisle, there simply was not a solid sense of connectivity to the images and story. That is not to say the images were not powerful and beautiful, because they were, but the sense of a place steeped in ancient beliefs (pixie-dusted with the sensuous awakenings of pagan revival) was much more palpable in THE WICKER MAN than it is here.

Naturally the vibe and mood of a 1973 production will always have a very different feel to a contemporary audience than a film made in 2012. The aura of mystery and mystique present in Hardy and Shaffer’s 1973 film are still very accessible and powerful to today’s audiences (and I hope those who see THE WICKER TREE without having seen THE WICKER MAN will seek out the original). Certainly the music by Paul Giovanni and Lodestone/Magnet lent a great deal of atmospheric magic to it, and while I did like some of the songs in THE WICKER TREE, I don’t see myself wanting to listen to the entire soundtrack from start to finish, as it doesn’t feel as much. Several years ago, a friend of mine in the UK created a series of 13 CDS containing psychedelic folk music from the late 1960s-early 70s inspired by the music of THE WICKER MAN, called “Lammas Night Laments” and distributed them among other fans. I simply can’t see that happening with this film’s music, as it doesn’t feel all of a piece (not having been based upon one clear concept, as Giovanni’s was with so much traditional Scottish music and several sets of lyrics from Robert Burns), nor does it contain the original’s power and beauty: Christopher Lee once said that Giovanni’s music was a profound achievement and I have to agree.

I don’t think THE WICKER TREE isn’t worth seeing; indeed I plan to view again with an eye towards seeing what lies beneath some of its very powerful visual motifs. But generally, the script has some problems I don’t think can be fixed merely by achieving greater familiarity with the film. The plot holes are not borne of complexity that makes itself more accessible with repeated viewings, they are simply examples of under-explored ideas and a poorly conceived balance of exposition to action. The intricate ideas beneath the WICKER MAN mystique may be complex, but can also be simply conveyed with the right choices of image, dialogue, music or sound. The great care and heart that went into the making of THE WICKER MAN feels lacking here, as if an artful wooden structure had been built, elaborate costumes designed and sewn, a huge pyre assembled, and all the villagers called forth, but the choosing of a suitable sacrifice was left to random chance.