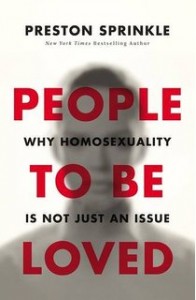

I just found out that the release date for my books about homosexuality (one for adults and another for teens) got moved up from the original Jan 2016 date to Nov 2015. As soon as I found out, I Tweeted the new release date and I got  some interesting responses that surrounded the same general theme (or critique): “Oh great. Just what we need. Yet another book about homosexuality by a white, straight, privileged male.” Some said that my books are only going to contribute to more suicides by gay teens. (Apparently, they didn’t read the titles.) One of the most colorful responses read: “You have your head so far up your racist ____ that you don’t think people of color are doing any work…” (that is, literary work related to LGBT issues).

some interesting responses that surrounded the same general theme (or critique): “Oh great. Just what we need. Yet another book about homosexuality by a white, straight, privileged male.” Some said that my books are only going to contribute to more suicides by gay teens. (Apparently, they didn’t read the titles.) One of the most colorful responses read: “You have your head so far up your racist ____ that you don’t think people of color are doing any work…” (that is, literary work related to LGBT issues).

While I deeply desire to heed good, solid, constructive criticism, I rarely pay attention to comments like these on social media, since none of them were good, solid, or constructive (though the one about the location of my head caused me to spit out my coffee in laughter!). But the general theme of the Tweets did get me thinking: Why did I write this book? Does the world really need yet another book by a white, straight, privileged male on an issue that I can’t identity with? Am I a racist bigot with amazing flexibility in my neck?

Here’s my rather long response.

First, I’m still not convinced that the LGBT question can be compared to an issue of race. Sure, there are some parallels—people of color have been (and in some ways still are) an oppressed minority, victims of systemic injustice that hardly gets noticed by the privileged majority. I used to think that systemic injustice didn’t exist. I used to think everyone has a fair shot at “the good life” by simply working hard and obeying the law. But then I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X (one of the most influential books I’ve ever read) and several other works by (and about) Dr. Martin Luther King and I realized that it’s not so simple. Injustice and racism have deep roots in our society and are often unnoticed by those who aren’t affected by them. And although we’ve made great strides over the last 100 years, we still have a long way to go.

Now, in some ways the LGBT community has experienced a similar measure of injustice that people of color have. I get that. I haven’t experienced it, but I get it. And I protest it. It’s evil. Anytime a human who bears God’s image is dehumanized like some sort of “other,” then that’s evil. And yes, as I argue in my book, the church has played a role in the dehumanization of gay people.

But is the LGBT question the same as the race question?

I don’t think it is. And, for what it’s worth, the vast majority of people of color around the globe not only agree with me but also resent the parallel. The question of race is an anthropological one. All people are created in God’s image. All people are, in the words of Psalm 8, “crowned with glory and honor.” The diversity that pervades humanity reflects the diversity of our Triune God.

But LGBT questions include, but can’t be reduced to, how one acts on their sexual desires. The questions are not (or shouldn’t be) about whether a particular type of human is truly human. And my Christian worldview prevents me from believing that some forms of sexual desires and actions are untouched by the fall and therefore inherent to who we are and who God wants us to be. The questions of race and the questions of sexuality are fundamentally different questions. To call me a racist—or any other non-affirming “traditional” Christian” a racist—is not only illogical but an offensive parallel to the many people of color who have suffered scathing injustice.

Second, am I a privileged, straight, white male? Yes. And there’s not much I can do about that. I’m also the son of divorced parents, raised by a single mom working three jobs, and I didn’t read a book until I was 17. I was—and in many ways still am—the village idiot. But I am privileged. I am a white male. I reap the benefits of a society that favors me.

And yet, I’ve held hands with Christian lepers in third (majority) world countries and stared into the face of people who have been, and will also be, treated like cockroaches by a society where advancement is next to impossible. I’m not an oppressed outcast. But I have seen systemic oppression ten times worse than anything the LGBT community is experiencing here in the West. But my outcasts friends view their societal status through the lens of Jesus.

Jesus.

The incarnate King born in a feeding trough.

The one who became an outcast in order to become a Savior. The one who reached into the depth of human pain and misery walked out of a grave-tomb to crown us as sons and daughters of the King.

My friends in the majority world actually believe this. The glory of Jesus illuminates their earthly status and reconfigures their view of oppression. They daily stare into a secure future filled with possibility and favor. And that’s where they find their identity—swallowed up in a risen King who knows a thing or two about persecution.

Yes, I’m a privileged, white, straight male. But I’ve tried to do all I can to enter into the pain of “the other” and learn about their hope.

Third, knowing that I’m not gay and don’t plan to be gay anytime soon, I did everything I possibly could to listen to, identity with, and feel the real pain and joy and confusion and frustration and oppression of LGBT people. And their  beautiful voices are heard within my book. Since I never write a book in isolation—I always write books from and within a community—I do believe that my whiteness and maleness and straightness has been tempered and reshaped by a healthy dose of enriching relationships with the LGBT people whose lives are inseparable from the words contained in my (aptly titled) book People to Be Loved.

beautiful voices are heard within my book. Since I never write a book in isolation—I always write books from and within a community—I do believe that my whiteness and maleness and straightness has been tempered and reshaped by a healthy dose of enriching relationships with the LGBT people whose lives are inseparable from the words contained in my (aptly titled) book People to Be Loved.

Fourth, I don’t think that LGBT people should be the only ones writing books about LGBT issues. I don’t buy the lie that humans are isolated individuals. We are not. We are community. What hurts one person hurts many persons. If someone punched my daughter in the face, it would hurt me differently but it would still hurt deeply. Perhaps even more than the physical pain inflicted upon my daughter.

Just because I’m not gay does not mean that the LGBT question does not affect me. Yes, of course, it affects me differently. It affects me less intensely, less personally. But it still affects me. The LGBT question is not just “their” issue; it’s “our” issue. To say that only LGBT people should be writing on LGBT issues is to reinforced the “us” versus “them” wall that needs to be destroyed with Berlinish passion.

My LGBT friends have been deeply hurt by the church and it usually has to do with persecution, isolation, dehumanization, and chastisement. It usually does not have to do with a gracious articulation of the church’s historical position on sexual immorality.

This hurts me differently, but it still hurts me deeply.

And that’s one of the reasons why I wrote this book. I intend People to Be Loved to be a fair and thorough evaluation of whether the Bible really does prohibit monogamous, consensual, loving same-sex relations. I also intend it to be an internal, prophetic critique of the unchristian posture that many Christians have had toward the LGBT community.

Fifth, I wrote this book as a teacher/pastor for many people who are searching for answers to a complicated topic. Hardly a day goes by where I don’t get a question about homosexuality from Christians who care. Christians who are trying to stay true to God’s word, both in terms of truth and love. How do I pastor the gay couple that just got saved? Does the Bible really prohibit consensual, monogamous, same-sex relations? Did such a thing even exist in the first century? How do you know? I need evidence. I need answers. I’m sick and tired of worn out, simple answers to complex questions. What did the Roman world really believe about same-sex relations and what bearing does this have on Romans 1 and 1 Corinthians 6? Why should we uphold the laws about homosexual relations in Leviticus 18 but not the laws about eating catfish and bacon in Leviticus 11? Why doesn’t Jesus mention homosexuality? Did he not have an opinion? And can Christians uphold a biblical sexual ethic and still reflect the scandalous grace that Jesus showered on people who were ostracized by the religious elite?

“Sorry. I’m a white, straight, privileged male. I can’t answer your questions even though I have answers to your questions.”

This would be irresponsible and, in itself, dehumanizing.

I wrote this book because I wanted to give other white, straight, privileged males (and non-white, straight or gay or bi, privileged or non-privileged males and females) some sort of resource that’s laced with grace and driven by truth about the church’s most pressing ethical question of the 21st century.

Lastly, circling back around to the main critique I’ve already received: Aren’t there already enough books written by straight, white, males?

No. Actually, there’s not. In fact, most of the books written by white, straight, males argue that the Bible does not prohibit same-sex relations. The only other white, straight, male, who has written an accessible yet well-thought-out book that comes close to my own, is Kevin DeYoung. But as the astute reader will see, our books are actually very different. For one, Kevin drew from the scholarly discussion about homosexuality, whereas mine directly interacts with it. (While my language is conversational and bloggy, my footnotes are extensive and thorough.) This isn’t a knock on Kevin’s book. As I said before, it’s an excellent resource. But mine will go into much more depth and provide more interaction with opposing views. (And for what it’s worth, I actually disagree with Kevin on several interpretive points.)

Moreover, Kevin wrote his book with one purpose in mind: To show that the Bible condemns same-sex behavior. And he argues his case well. My book, however, addresses the same-sex prohibitions quite thoroughly, but it also challenges people on both sides of the debate. I agree with the church’s historic position on same-sex relations, but I disagree both with its historic posture toward LGBT people and some of the lame arguments it’s used to support its theological views.

At the end of the day, I hope and pray that God isn’t disappointed that yet another white, straight, male wrote a book about homosexuality. If He is, then may He cause it not to sell. That is my current prayer and I ask that you lift up the same plea to our King enthroned on high.